For Britain to solve its economic problems, it needs to stop lying to itself about its past

On trade, ‘Empire 2.0’, and the truth in Liam Fox’s nonsense.

In May 1840, William Gladstone said that he lived “in dread of the judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China”, and that he couldn’t think of “a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace”.

He was talking, of course, about the Opium Wars. If you need a reminder, they’re the ones in which the UK used its superior naval power to murder Chinese people until they finally allowed British drug pushers to flood their country with the then equivalent of heroin.

One of those industrial scale drug dealers – a Scotsman called Thomas Sutherland – understood that every big trade needs finance. And so in 1865, he and a few others founded the Hong Kong Shanghai Banking Corporation. HSBC is now the UK’s third biggest company, and still bogged down in drug-money scandals.

Britain’s second biggest company, BP, was founded as “Anglo Persian Oil” so that the UK could plunder newly found fossil fuels from Iranian soil. Our biggest, Shell, is similarly a long-term beneficiary of imperial might.

Today, in the wake of Phillip Hammond’s budget, Britain’s multiply disgraced trade secretary Liam Fox is meeting with more than 30 Commonwealth ministers in London in an attempt to discuss multilateral trade links. While this is exactly the sort of strategy that many Brexit supporters have long advocated, The Times has reported that the plan is derided by some civil servants as “Empire 2.0”. Which seems fair: Fox has a history of colonial yearning.

When the likes of Fox get all weak-kneed about the old days of the empire, we should perhaps give them the benefit of the doubt, and assume that their nostalgia doesn’t extend to the genocide, forced famine, concentration camps, castration with pliers, or rape with broken bottles, though the willingness to ignore all of these does tell us something important about the British psyche. What people are interested in returning to really is that other key element of imperialism: plunder.

The trade secretary’s strategy, tied to Tory out-rider Melanie Phillips’ vainglorious ultra-nationalism in the Times this week (top tip: never challenge the Irish to an argument about the history of these islands), is merely an official attempt to execute an economic strategy based on a growing cultural trend. In recent years, we’ve documented on openDemocracy the expanding fashion for what we’ve called British Empire Kitsch. From the ever-flashier bling of November’s annual poppy-fest, (which takes place, as it happens, on the anniversary of the date that my great-grandfather was declared ‘missing presumed dead’ at Ypres, and which ‘commemorates’ his death and millions more with flashy light displays and poppies on the side of bombers); to Keep Calm and Carry On mugs; to Jubilee street parties bedecked with bunting in the design of the same Union Flags which flew over some of the first concentration camps; to that same blood stained icon becoming a fashion symbol; the years of the long recession have brought with them a nostalgia for a time when life was easier, and Britain could simply get rich by killing people of colour and stealing their stuff.

All of this is made possible by lies: the lies many of us were told about what our great-grandparents were up to in India, the lies we told ourselves when we decided not to look too closely, the lies we told the peoples we subjugated: Britain is a country built so firmly on deceit, dishonesty and backstabbing that the symbol on our national flag is not just a double-cross, but a triple.

But it’s not just about the traditional opium smoke of nostalgia and untruth. The yearning for the days of empire is the result of more than the old fashioned desire to return to some imagined glory days. At the core of what Fox says, there is in a way an important honesty. For the six years that George Osborne was Chancellor, the government spent its time trying to persuade people that our country’s biggest economic problem was our fiscal deficit. There is an interesting debate to be had about whether he really believed this, and failed, or was using it as an excuse to flog off public services and drive down wages, and succeeded, but that’s another question. In reality, the deficit which the UK really should be worrying about, and debating solutions to, has long been that in trade.

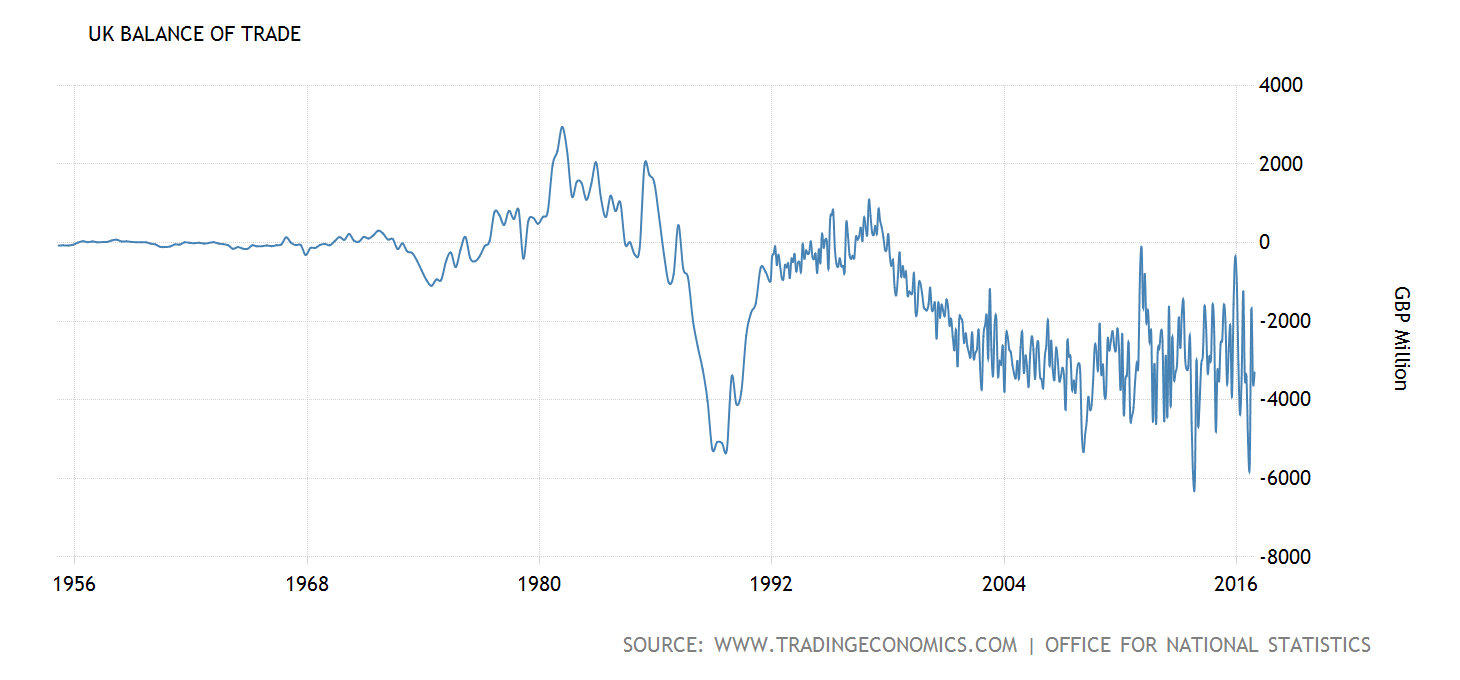

UK balance of trade, from tradingeconomics.com

And here, the stats really are serious: Britain’s balance of trade averaged minus £1458.28 million from 1955 to 2016. Our trade deficit has become chronic. As Des Cohen, who was in the Treasury’s economics team at the time, wrote for openDemocracy back in November, it was the realisation that the Commonwealth wasn’t a big enough market for exports that lured Britain into join the EU in the first place. But, while leaving the Common Market certainly won’t help, joining it didn’t solve the problem either: our long term trade figures are a disaster. What Fox’s meeting highlights is that the government is being forced by Brexit to reveal its thinking in this area, and show that it really doesn’t have any better ideas than falling back on what the Financial Times’ James Blitz calls ‘delusions‘ and wishing that the last century hadn’t happened.

There’s another way to look at this problem. As the New Economics Foundation’s Laurie Macfarlane told me when I interviewed him last week, “much of the increase in paper wealth… that’s happened in the UK… since world war two, has actually been not a result of producing more stuff: it’s basically the result of increases in house prices: asset price inflation.”

In other words, since the end of world war two – which marked the beginning of the end of the British Empire, the UK hasn’t really figured out how on earth to pay our way in the world. Even during the days of imperialism, our trade successes came at the barrel of a gun and with the advantage of being at the centre of a vast sterling zone: it’s not because of a nose for the market that BP and HSBC had their early success, but because of the gunships sat in the port behind them. As, over the decades, country after country has secured independence and left the Sterling Zone, we’ve resorted to inflating the prices of the assets we built up over a couple of centuries and more of empire, and rapidly flogged them off.

Of course, much of this strategy still relies on our imperial remnants. Our Overseas Territory secrecy areas put London at the centre of the world’s money-laundering nexus. As Donald Toon, head of the National Crime Agency, described to the Financial Times “the London property market has been skewed by laundered money. Prices are being artificially driven up by overseas criminals who want to sequester their assets here in the UK”.

The right loves to talk about how Britain is a ‘trading nation’. But that, of course, is just another lie. The truth is that we are terrible at trade. We buy much more than we sell, and produce little that anyone wants. We’re so bad at selling things to the rest of the world that the government has started producing patronising adverts trying to coax British businesses into the international market. Even in the days when people did pay for our stuff, it was usually under duress.

The process of Brexit is likely to be a series of humiliating meetings in which the country is forced to accept a procession of ruinous trade deal terms – ruinous, at least, for the majority of the population. As it does so, expect Dr Fox, or whoever succeeds him if he’s caught in another scandal, to return home, waving the Union Flag ever more vigorously, and insisting in ever more pompous terms that this is another great victory for the Mothership Britannia. People might even believe it. We’re good at accepting lies.