Central banks need to step up and help tackle climate change

The Bank of England. Captain Roger Fenton / Flickr. Public domain.

World leaders have come out fighting in response to Donald Trump’s decision to pull the United States out of the Paris Climate Change agreement. The threat posed to all of us by climate change and environmental catastrophe requires urgent action – so will Trump’s decision derail the world’s ongoing efforts to keep global warming below 2 degrees this century?

The decision has powerful symbolic impacts. The U.S. is the world’s largest polluter after China as well as a major funder of efforts in developing countries to mitigate and adapt to the catastrophic impact of climate change. A recent estimate put the cost of the investment needed to meet the 2 degree target at $5-6 trillion per annum, or around 1/3rd of the European Union’s GDP.

All of this paints a bleak picture – with great powers making reckless decisions which could have a devastating impact on our lives. But while Trump’s intransigence might be an obstacle impossible to overcome, are there other levers of power available for us to influence?

We need fresh ideas. We must stop thinking of ‘green’ finance as a separate entity and begin to consider the role of ‘mainstream’ finance and money flows in seriously tackling climate change. Central banks and financial regulators hold considerable power in steering existing financial flows and creating new ones. So what impact is that currently having upon our environment?

Not so green Quantitative Easing

An example is the European Central Bank, which is currently creating €60bn a month in new money under its ‘Quantitative Easing’ program, which is being used to purchase a range of public and commercial assets across Eurozone member states. They have so far bought £82 billion worth of corporate bonds. The Bank of England, meanwhile, completed its £10bn corporate bond programme in May.

Environmental sustainability and climate change are absent from the criteria central banks use to choose the types of corporate bonds to purchase. Rather they are ‘market-neutral’, basing their decisions on much the same criteria as any other large commercial investor: they purchase high quality, ‘investment grade’ assets. But new research by the London School of Economics’ Grantham Institute released last week suggests that when it comes to carbon-intensity, corporate QE purchases are favouring high carbon sectors.

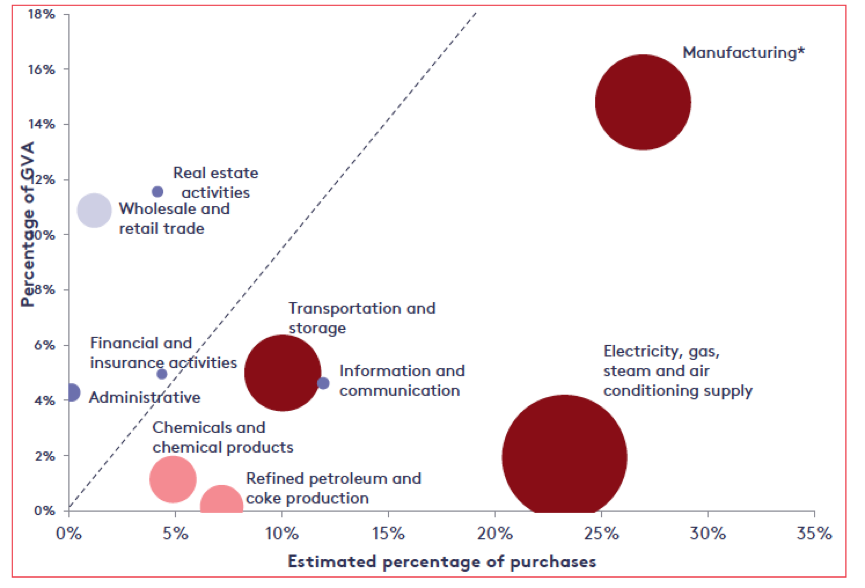

The researchers found that 62% of ECB corporate bond purchases were from manufacturing, electricity and gas production which are responsible for almost 60% of Eurozone area greenhouse gas emissions but only 18% of Gross Value Added (GVA). Almost 50% of the Bank of England’s purchases were from manufacturing and electricity production, which produces 52% of emissions but contributes just 11.8% GVA (figure 1).

Figure 1: Contribution of ECB corporate sector purchases programme to the economy (GVA) and greenhouse gas emissions (size of circle)

Source: Maitikainen et al, (2017)The Climate impact of quantitative easing, LSE Grantham Institute, page 16

Source: Maitikainen et al, (2017)The Climate impact of quantitative easing, LSE Grantham Institute, page 16

The research found that the most carbon-intensive sector by emissions, utilities, made up the largest share of purchases for both the ECB and the Bank of England. Meanwhile, renewable energy companies are not represented at all in either Banks’ purchases or the fast growing ‘Green Bonds’ Market. This is despite the existence of the British Green Investment Bank, recently privatised, and the European Investment Bank which has a strong focus on green investment. None of these types of asset have a sufficient credit rating to be eligible for central bank purchases.

Similar to the symbolic impact of the decision of the American President, a central bank has huge ‘signalling’ power because of its unlimited ability to create new money. When Mario Draghi, the ECB’s president, announced that he would do ‘whatever it takes’ to prevent any Eurozone country suffering a banking crisis, speculative attacks against weaker Eurozone finally stopped. By supporting big utility companies, central banks may be unwittingly supporting a ‘carbon bubble’ in sectors that otherwise might have seen faster price falls.

Unlike Trump, a number of central banks clearly recognise the risks to financial stability posed by climate change, as Mark Carney’s “Tragedy of the Horizon” speech made clear.

This provides a glimmer of optimism for change. So far central banks’ focus has been confined to encouraging greater ‘disclosure’ by financial market participants in the hope that better information will lead to a natural shift away from carbon sectors, rather than central banks examining their own market activities.

But central banks must go further. Institutional investors are already accounting for environmental and social governance criteria in to their investment decisions. With the world rocked by Trump’s decisions, it is more urgent than ever for us to call upon central banks to do the same and take a step towards mainstreaming ‘green’ finance – for the sake of all of our futures.