Inequality: how we got here, and what should be done

Protest and demonstration against economic inequality. Darren Johnson / iDJ Photography / Flickr. Some rights reserved.

A great deal has been written in recent years on the topic of inequality. The books of Thomas Piketty and the late Tony Atkinson are just two recent examples. It is hard to believe that anyone can be unaware of the issues and the possible explanations of why there has been such a massive shift in income and wealth distribution in both rich and poor countries. And yet it is still possible to be surprised at what is going on at the highest echelons of business. Here is just one example, as reported in the Guardian earlier this month:

Burberry is to hand Christopher Bailey shares worth £10.5m next month when day-to-day management of the luxury goods retailer switches to a newly recruited chief executive. Bailey is to receive 600,000 of the 1m shares he was awarded in 2013, at a time when the company was concerned he might be poached by a rival. Bailey will receive the rest of the 1m shares at a later date and at the current share price of £17.65 the 600,000 that he will receive are worth about £10.5m.

The annual report published on Tuesday shows that Bailey was paid £3.5m last year – up from the £1.9m the previous year. While he waived his entitlement to any annual bonus for the year, his total was boosted by a £1.4m payout from a further award of shares in 2014. ….In 2014 the company had endured a bruising annual meeting with its shareholders, who voted against its remuneration report to protest about Bailey’s pay. His pay deals also include a £440,000 allowance to cover clothes and other items.

Bailey’s salary will remain at £1.1m when he becomes president next month, following a year in which underlying profits fell by 21%.

Burberry isn’t exactly at the forefront of technical innovation and nor is it a company supplying a product that most of us would consider essential to life and limb. It caters of course to the global rich and its success until recently in expanding sales has depended on precisely the shift in income and wealth that has been measured by Piketty and others. But relative to average wages in the same company and to median household income in the UK, the scale of the payments to Bailey seem unreasonable. This is someone who has presided over a 21% fall in profits, and yet is still rewarded by a huge set of payments. What does this say about corporate governance and any supposed relationship between payment and performance?

It is perhaps unsurprising that in the land of Thatcherism the UK comes out very unfavourably in international comparisons of income and wealth distribution. In the UK the top 10% of households have disposable income 9 times that of the bottom 10%. But the level of inequality is much higher for original pre-tax incomes where the top 10% is 24 times higher than the bottom 10%. It is even worse than this within the top 10% where the level of inequality is greater; the top 1% of households on average had an income of £253,927 and the top 0.1% had an average income of £919,882 in 2012. The UK is the 7th most unequal country in the OECD, and the 4th most unequal country in Europe.

In the case of wealth, inequality is even greater. The richest 10% of households hold 45% of all wealth and the poorest 50% have 8.7%. Within the OECD countries the UK has a gini coefficient for wealth inequality a little higher than the rest of the members [73.2 compared to 72.8].

In an interesting paper in 2012 the Bank of England argues that more or less every citizen gained to some degree from the fact that monetary expansion after the 2008 crisis generated additional demand and growth in GDP of 1.5 to 2.0%. Perhaps, but more importantly quantitative easing (QE) both directly and indirectly increases asset prices, and since ownership of financial assets is skewed most of the capital gain accrues to those with the largest holdings. Thus it is the top 5% of households in the UK hold 40% of financial assets who gained the most.

This is equivalent to the top 5% each receiving £128,000 as a result of QE in the years prior to 2012. Since QE has continued to be central to monetary policy in the UK since then, the richest have continued to be the main beneficiaries. It is reasonable to assume that in the 5 years since the Bank made its estimates that another £130,000 or so has been added to the wealth of each of the top 5%.

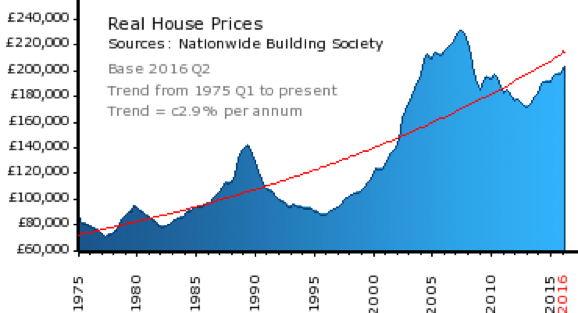

It is also worth noting that the UK has had massive property price inflation in part as a result of the liquidity generated by QE. Again, the greatest benefit will have accrued to the richest segment of the population. This gain is an additional transfer to the top 5% since real gains on property were excluded from the Bank’s estimates. The scale of the rise in house prices both has been enormous. Nominal house prices on average increased between 1975 to 2016 by more than 800%, while real house price growth (after inflation is considered) was 333%. The following chart from Nationwide the biggest UK lender for housing finance maps the trend over the whole period since 1975.

What we face in the UK and elsewhere in the EU is a situation of deep and growing income and wealth inequality which in part has its origins in globalised trade but also in trends in technological development that substituted precarious work for previously well paid and secure employment. But we also witness governments both in the UK and across the EU following tax policies that are increasingly regressive in their impact, with greater dependence on indirect taxes and reductions in the degree of tax progressivism in income taxes.

In practice corporate taxes are increasingly easily to avoid, which also raises the returns to owners of capital. Meanwhile, the power of labour organisations has weakened which has enabled capital to grab a larger share of net product and hence a higher share of national income and wealth. To these forces we have also identified the actions of central banks who through their activities have directly and indirectly caused further income and wealth inequality.

Present levels of inequality threaten social, economic and political stability. It is now generally agreed as to what to do, but the problem is that years of increasing inequality have embedded the interests of the rich and powerful such that governments more or less everywhere have been captured and are no longer representative of their populations. But the structural forces at work will make it difficult for governments to continue with present policies, and they will have little option but to change direction. Populism and the rise of extreme parties of the left and right will inevitably lead to change, but why wait for this to happen?

The broad outlines of policy reform are clear:

- Monetary policy needs to revert to its more traditional role with a much reduced level of dependence on QE. Savers need to be offered higher real rates of interest and credit needs to be brought under more effective control. Banks and other financial intermediaries need to be effectively regulated and their stability should be the focus of the monetary authorities. Where QE is continued it should be used to serve the interests of the country and not the rich few, and this would mean using monetary expansion for financing public investment in a sustainable way – both social and economic investment.

- Fiscal policy needs to be given a much greater weight and needs to become much more progressive in terms of tax structure. The current regressive nature of the tax system needs to be reversed with much greater reliance on income taxes and much less on indirect taxes. Corporate taxes need to be increased and loopholes closed so that the effective tax rate is moved closer to historical levels. In particular corporate taxes should be based on where revenue is received rather than on profits so as to make it much more difficult for companies to avoid taxation. Wealth taxes need to be made more effective and loopholes closed especially in relation to the passing of wealth between generations which is presently a major avenue for processes of inequality to persist and deepen over time.

- Political reform is essential so that the role of money and corporate power is removed from the political process. This has become even more critical now that it is evident that social media such as Facebook have been infiltrated by organisations that manipulate data and information in the interests of the rich and powerful. Political systems have become corrupted and urgently need reform.

- Wages are too low and this threatens economic stability. It is critical that real wages be increased in part through changes in wage policy in respect of public sector employees where there has been wage restraint, and in part through policies to strengthen organisations representing the interests of labour. The insecurity of work especially in the so called ‘gig’ economy needs to be addressed via regulations which require workers to be treated as employees and not as self-employed. The weakening of the bargaining power of unions should be reversed through public policy since this is an effective way to raise wages and reduce the dependence of workers on debt and fiscal transfers from government. The shift in the shares of national income to capital has to be reversed so that employment incomes can be raised and with it increased consumer expenditure. Economic growth nearer to long term trends is essential if employment and income levels are to be restored.

Will the above reforms happen? Time will tell, but the clock is ticking. If structural reforms are not undertaken by government then we will all reap the consequences – and these will not be pleasant.