The Queen of the Cayman Islands

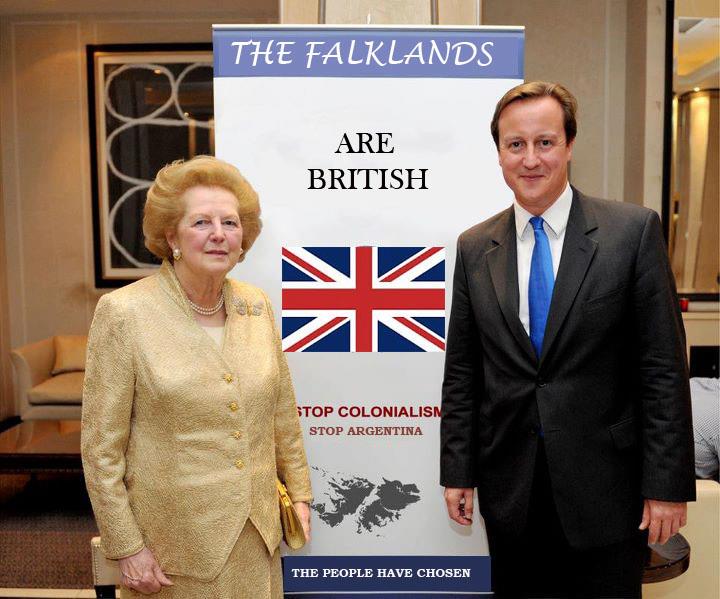

“The Falklands”, they said, “are British”. They are so British that we went to war for them. We also went to war for Akrotiri and Dhekelia, the British Overseas Territories on Cyprus. That’s where Saddam Hussein was supposedly able to get his weapons of mass destruction to within 45 minutes. And, less than a year ago, we were measuring ourselves up against Spain when they were threatening Gibraltar.

The Cayman islands are British, too. And Bermuda. And the British Virgin Islands – they even put it in the name.

Specifically, they are British Overseas Territories, the last vestiges of empire. Their citizens are entitled to British passports. They are, as much as English or Scottish or Welsh or Northern Irish people, subjects of Queen Elizabeth II.

And so when said Queen is revealed to store millions of pounds of her wealth in the Cayman islands in order to avoid paying the Treasury for it, it’s a misunderstanding to treat this as unpatriotic. It’s a misapprehension to imagine that the term ‘overseas’ means foreign. Tax dodging is as British as fried breakfast, the Bengal famine, and castrating Mau Mau leaders.

Like any good parent, Her Majesty loves her country just as we are. And what we are is the world centre for tax havens and secrecy areas.

The reason this story is so resonant is that it brings together the two ends of the British constitution. It’s the collision between the bling we parade in public and the cobwebs lurking in the corners. It forces the celebrities whose personal stories are used to maintain popular support for our empire state into the same narrative as the network of tax havens and secrecy areas, with London at its centre, which is how Britain’s elite maintained its wealth as land empire dissipated.

I often ask British people what they know about our Overseas Territories: how many there are, what their names are, where they are, how big they are. I bore my friends by delighting in telling them that Britain is responsible for more penguins than any other country on earth and more land in the Southern Hemisphere than the northern.

But the reason I do is this: the British constitutional issue which impacts on most people in the world is not our awful election system. It’s not even the unelected House of Lords, nor the fact that Westminster is the most centralised parliamentary system in Europe – especially for those who live in England outside London, and enjoy no serious devolution.

No, the piece of our uncodified constitution which matters most is the parts that mean that most of the wealth, and most of the biodiversity, for which the British state is ultimately responsible lies not in this North Atlantic archipelago, but in our fourteen Overseas Territories; the parts which allow the crooks of the planet to hide their ill-gotten gains in island chains protected by the might of the British state – and to launder their money through the centre of that web, the City of London, and the capital’s ever-inflating property market.

It’s the part which led the Tax Justice Network to rank the UK as the world’s most important player in tax havens. It’s the part which famously led the top mafia expert, Roberto Saviano, to call the UK “the most corrupt country on earth”. It’s the bit which ensured that more than half of the companies in the infamous Panama Papers were registered in Britain or its Overseas Territories. It’s the section which helped ensure a trillion dollars have been stolen from African countries since the UK and other European countries ended formal colonisation in the 1960s and ‘70s.

None of this is incidental to Britain. It’s core. The British state was built to manage an empire. It’s central constitutional principle – that the crown in parliament is sovereign – is asserted on the assumption of global dominance. It’s ability to stave off revolutions as they set most of Europe aflame came from the capacity of its elite to placate the anger of the domestic working class by parting with small amounts of the proceeds of plunder.

These days, the direct plundering is usually done by others. Britain with its Overseas Territories acts as the middle man – the safe haven. Support for the system is secured through increasingly shrill demands for loyalty to Queen and country, expressed culturally through increasingly tasteless British Empire Kitsch, and by channeling rage at outsiders: immigrants, Europe, whoever else can be blamed as wages shrink and the wealth of the ultra-wealthy mysteriously vanishes from sight.

And at the centre of all of this is the Queen, with her Jubilee street parties, and her adorable great-grand-children, the world’s biggest celebrities in an era of TV-celebrity rule.

And so, yes, the Queen stores millions of pounds of her wealth in her Dominions Beyond the Seas, as her original title called them. Why wouldn’t she?

The Cayman Islands are British, after all.