If Philip Hammond wants to reduce debt, he must draw a line under austerity

Image: US Embassy London, CC BY-ND 2.0

UK Chancellor Philip Hammond is likely to use his Budget speech on Wednesday to declare that the UK has turned the corner on public debt. Recent tax receipts have been higher than expected and the deficit continues to fall. As a result, we are likely to see some small but headline-grabbing giveaways to a nation weary of austerity.

He is less likely to note that the Coalition and Conservative governments have so far missed all of their self-imposed debt targets. Or that beyond the short-run jump in tax revenues, the longer term outlook is darkening: the Office for Budget Responsibility has finally conceded it has been guilty of “supply-side optimism” and will downgrade growth forecasts. Even the revised forecasts are likely to be unrealistically optimistic.

The chancellor is also unlikely to discuss a different kind of debt: that of households. Household debt, particularly unsecured debt such as credit cards and car loans, is growing rapidly. The total stock of unsecured debt has reached around £200bn and is increasing by around £20bn per year.

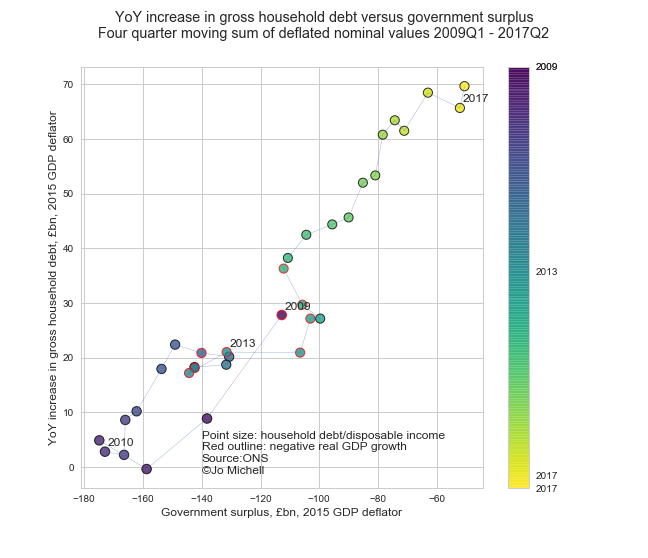

The relationship between deficit reduction – austerity – and the growth of household debt is remarkably stable. Adjusting for inflation, for every £2bn in public sector deficit reduction, the annual rate at which households have taken on new debt has increased by £1bn. Over the longer term, the connection between the two is surprisingly persistent – and also appears to work in reverse. During periods in which the deficit has been growing, household debt accumulation fell.

So the chancellor’s inevitable claim that the UK’s debt problem is finally under control should be taken with a large dose of salt. By squeezing incomes, rolling back crucial public services and refusing to invest for the future, governments since 2010 have consigned the UK to nearly a lost decade of stagnating wages and incomes.

The Bank of England has done what it can to make up for the shortfall in spending power but monetary policy is the wrong tool for the job. In holding interest rates at nearly zero and pumping money into the financial system, the Bank has managed to get banks lending again. Unfortunately, this lending has not been to businesses, for productive investment, but to households.

These households, facing an unprecedented squeeze on incomes, have relied on consumer credit to make ends meet. Household consumption has been the driver of economic growth in recent years. Growth in mortgage lending, in the absence of wage growth, pushes house prices up, putting home ownership ever further out of the reach of young people.

If the current pattern were to persist – a big if – and the chancellor were to achieve his “general aim” of a balanced budget, household debt would then be increasing at a rate of around £100bn per annum.

This looks unlikely in reality. The apparently stable relationship between the public finances and household borrowing may break down – as macroeconomic relationships usually do. More likely still, the chancellor will fail to achieve a balanced budget. Even he no longer claims this can be achieved within the current parliament.

Instead, the chancellor needs to concede what many of us have said all along: the public sector deficit is the wrong target for policy and austerity was a mistake – a deadly one. What is needed from this budget is plainly obvious: higher public investment. With interest rates close to zero and both public and private sector investment at historically low levels, the chancellor must reverse the policy direction of the last seven years.

A programme of public sector investment, along with a carefully implemented industrial strategy, is the most promising solution to the problem underlying most of the UKs current woes: very weak productivity. Without productivity growth, long run increases in income and declines in debt ratios – both public and private – will be impossible. Evidence is growing that weakness in productivity is the result of austerity – it is caused by lack of demand.

Such a reversal would be politically difficult for the chancellor. It would require him to admit, at least implicitly, that the austerity policies imposed over the last seven years were based on the lie that public debt is the most important issue facing policy-makers. It is clear that the public willingness to tolerate further cuts to wages, living standards and public services is exhausted. It is time for the chancellor to change course.

Paradoxically, this is likely to be the best way to reduce the level of debt. Higher investment should spur productivity growth, allowing for wage rises, increases in tax revenues and, ultimately, less reliance by both households and the public sector on debt.