Film review: The Spider’s Web – Britain’s Second Empire

On 1 December I attended SOAS University for a screening of the film ‘The Spider’s Web: Britain’s Second Empire’, co-produced by film maker Michael Oswald and John Christensen of the Tax Justice Network, and hosted by the SOAS Open Economics Forum and Dr. Ourania Dimakou.

The Spider’s Web offers unique insight into the British Empire, both past and present, and its colonies and far flung outposts. This is a story which, if known at all, is often understood through a rose tinted view of what that British Empire actually represented. The Spider’s Web details how the former Empire was transformed after World War 2 into a new financial empire of offshore tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions.

Nicholas Shaxson, author of ‘Treasure Islands’, notes that the historians Cain and Hopkins called the City of London the “Governor of the Imperial engine”, so it is perhaps no surprise to learn that ‘the City’ still controls the reigns of Britain’s second-run financial services empire, with as much as 25% of the global offshore market controlled by Britain and its satellites. As City University’s Ronan Palan observes:

“The City of London is a truly unique and interesting phenomenon, which should have attracted the attention of political scientists and economists, but I don’t know of anyone, who has systematically studied the Corporation of London and its impacts on policy and economic policy.”

The City of London and the Bank of England, experiencing a crisis of legitimacy marked by Britain’s declining global influence following World War 2 and the Suez crisis, facilitated the transformation of former British territories and dependencies such as the Cayman Islands and British Virgin Islands into tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions, taking a relaxed view of increasing corruption risk provided that the monetary flows benefited the UK. As the Bank of England noted:

“There is no objection to their providing boltholes for non-residents, but we do need to be quite sure that in doing so, opportunities are not created for the transfer of UK capital to the non-Sterling area outside UK rules.”

The growth of the so-called “Eurodollar” market — an unregulated form of lending, based in London but conducted in US Dollars via a separate set of books and thus considered “offshore” (elsewhere for regulatory purposes) — helped enable the bypass of cross-border capital controls put in place under the post-war Bretton Woods agreement.

Alex Cobham, Director of the Tax Justice Network, explains how the Eurodollar market was ultimately about taking economic activity conducted in one country, and pretending it occurs elsewhere:

“It’s about creating a legal space where you pretend activity is taking place. You’re taking activity from a place where it is regulated and taxed, and pretending its happening elsewhere. Now where, doesn’t really matter. It’s just elsewhere.”

The Eurodollar market expanded rapidly, reaching $500 billion by 1980 and by 1988 $4.8 trillion. By 1998, nearly 90% of all international loans were made via the unregulated offshore markets.

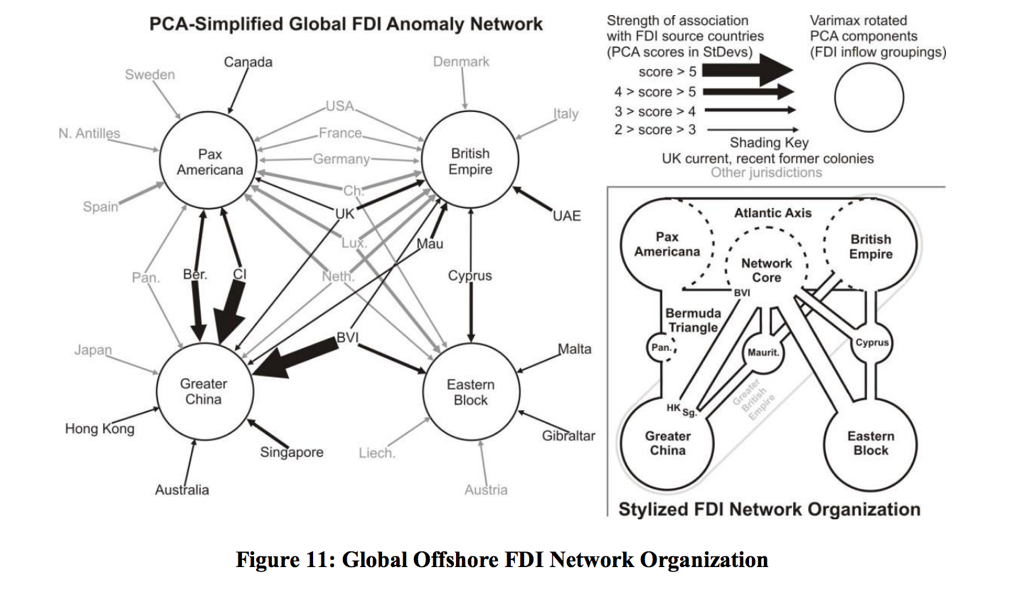

This diagram via Haberly & Wojcik illustrates the geography of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and the relative dominance of Britain and the territories of its former Empire.

The City of London, Bank of England and Eurodollar markets deliberately allowed banks, corporations and wealthy elites to bypass the rules of the capitalist game — shifting wealth offshore and thus undermining the social contract and the post-war welfare state now visibly in collapse around us.

Clement Atlee, the post-war Labour Prime Minister remarked:

“Over and over again, we have seen that there is a power in this Country, other than that which has its seat at Westminster. The City of London, a convenient term for a collection of financial interests is able to assert itself against the Government of the Country. Those who control money, are able to pursue a policy, at home, and abroad, contrary to that which is decided by the people.”

One of the criminal banks which grew out of the deregulated City of London was BCCI – which quickly became the bank of choice for drug runners, mafia bosses and intelligence agencies, much like the role HSBC performs today.

BCCI, which collapsed in 1991 following US enforcement action related to money laundering, was at the time the 7th largest bank in the world. A young Fred Goodwin who would go on to run RBS (at the time working for Deloitte Touche) ‘led’ the complex insolvency of BCCI bank.

Much of what we know about Britain’s Second Empire can be attributed to the tireless work of the Tax Justice Network, including Nicholas Shaxson, John Christensen (a former Deloitte Touche economist and advisor to the Government of Jersey) and leading academics including Prem Sikka and Ronan Palan who feature prominently throughout the film.

The film provides viewers with both a technical and a moral analysis of what tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions do — creating opportunities for tax, legal and political arbitrage — and lays the blame at the door of the real perpetrators, the Big 4 accountancy firms (EY, Deloitte, KPMG, PwC).

The cancerous effects of the ‘Revolving Door’ are documented in the film through the lens of highly effective direct actions by UK Uncut who targeted former HMRC boss Dave Hartnett and his tax “sweetheart deals” with Vodafone, BT and Goldman Sachs.

A highlight is the disruption of a private tax planning dinner hosted by Harnett, who is presented with a “golden handshake award” by the intruders for services to tax avoidance in front of a group of suited, booted and visibly confused paying guests.

The Spider’s Web gives an excellent overview of the scale of the global tax dodging problem and its corrosive effects on democracy. As John Christensen observes:

“People think the National Rifle Association (NRA) is a powerful lobby, but to be honest they’re amateurs next to the City of London. The City UK uses its power in so many discreet ways, they don’t need to be that upfront about it, they’ve got MPs and Ministers in their pockets going in and out via the revolving door.”

The City UK was created by Chancellor Alastair Darling after the 2008 financial crisis, precisely to establish a stronger financial lobby in Westminster and Brussels. It is from the unelected, unaccountable City of London that, we should really be having the conversation about “taking back control.”

Discussion on solutions is left to five concrete proposals in the final scenes, which was followed by a lively Q&A session which spilled over into discussion over wine & nibbles.

SOAS host Dr Dimakou reflected on the fact there were not more critical UK academics interviewed on tax justice issues in the film. Perhaps this is because, as John Christensen observed, leading economics journals tend to avoid featuring critical academic work on tax justice issues.

Lack of widespread academic engagement with tax avoidance could also be due to other factors, such as a lack of academic grant funding for research on tax dodging, the increasing reliance of the UK third sector and NGOs on grant funding from tax avoiding donors. Or the the fact critical academics such as Prem Sikka often find themselves isolated within professional accounting bodies such as the ICAEW.

It turns out that critical voices being ignored is not restricted to the academic and accounting professions. During the Q&A, Director Michael Oswald said that The Spider’s Web had been entered into over 50 film festivals, receiving warm feedback, but curiously not being selected to feature. The response from the Atlanta Docufest selection panel is typical:

“We just wanted you to know that you made it to the final round of judging, but since we only have three days of screenings, we had to cut so many great films. Although we can not include your project this year, please keep in mind, you scored the second highest scores from our panel.”

The subtext of The Spider’s Web is that Britain is yet to face its own history. In a desperate attempt to cling to empire, The City of London threw open its arms to criminal dark money from all over the globe. This is why mafia expert and author Roberto Saviano labels London “the heart of global corruption”.

Until Britain is forced to confront the realities of its Empires, both colonial and financial, there is little prospect of real change. It’s no coincidence state broadcaster the BBC refuses to air the film.

Thankfully, with a fracture in the neoliberal order sparked by the election of Jeremy Corbyn there is now a growing thirst for radical political change and transformational economic ideas. It is now incumbent upon all of us who desire change to work together to tame the power of the City of London and its offshore satellites, and to free democracy from the shackles of neoliberalism.

As Tax Justice Network Director Alex Cobham observes:

“We have country after country around the world where the lack of financial transparency, about taxation, about ownership, about corruption, has undermined the extent to which governments deliver representative policy making for their citizens.”

Why not get involved and help put an end to corporate capture, censorship, and corruption by hosting a screening of The Spider’s Web in your local community. Discuss what action can be taken locally to help transform our broken economic model which sees wealth plundered from the four corners of the globe, laundered and stashed in London’s dysfunctional property market.

To host a screening: contact info@queuepolitely.com

Twitter: @spiderswebfilm

Facebook: www.facebook.com/Spiderswebfilm

Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/ondemand/spiderswebfilm

Disclaimer: Joel Benjamin was interviewed for the film on issues of PFI and tax avoidance.