Out of time: the fragile temporality of Carillion’s accumulation model

Image: Elliott Brown, CC BY-SA 2.0

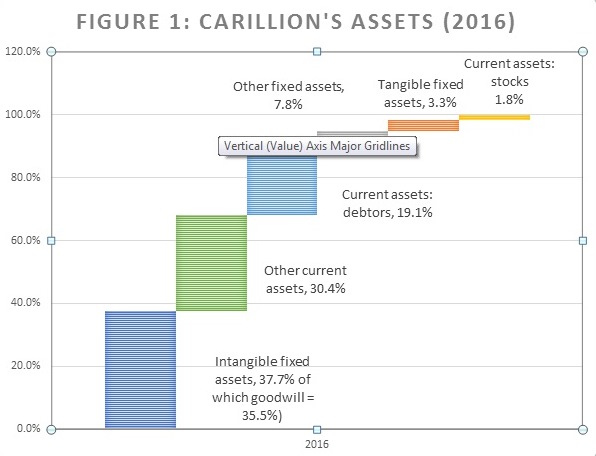

Look anywhere on Carillion’s website and we see metaphors for its supposed tangibility and strength, from the way it advertises its Tarmac Group heritage to its list of construction achievements which in fact precede its inception. The website projects an image of a company steeped in all things concrete and solid. However, as Carillion moves into liquidation it is evident it was anything but. By 2016 Carillion’s tangible fixed assets were just 3.3% and stocks 1.8% of its total assets. Much of its balance sheet was instead made up of intangibles (37.7% of total assets), of which almost all was goodwill (35.5% of total assets) (Figure 1). The value of that goodwill depended on Carillion continuing as a going concern, which is not now an option. Creditors now want their money back, but Carillion do not have assets which can be sold to make them whole.

Carillion is the very epitome of the modern financialized firm and its liquidation tells us much about risk in this phase of financialization. The Carillion financialization story is not one of distributional struggles between stakeholders in linear time, where dividends and share buybacks come at the expense of either wages, employment or investment in a zero-sum way. Employment and average labour costs actually rose between 2012 and 2016. Carillion’s financialization story is about how firms manipulate their balance sheet to intervene in the temporalities of income and obligation; and how this may create unanticipated inter-temporal tensions.

This view of financialization owes more to critical accounting than political economy. Critical accountants such as Hines (1988); Hopwood (1986); McSweeney (2000); Morgan (1988); Robson (1982, 1984) have long argued that accounting is a process which constitutes financial reality by inscribing a particular temporality or temporalities. Processes like discounting or depreciation are future-oriented and require the inscription of particular time periods. The assessment of goodwill under International Financial Reporting Standards rules are a case in point. At one level, goodwill is simply the difference between the market value and book value of a firm recorded at the point of acquisition. But this difference in price is supposed to reflect both an assumption about the future income streams likely to accrue to the holder of the underlying assets and the future discount rate to acknowledge the many factors that could affect the future-present value of that income (such as the future costs of capital). When a future emerges that looks very different to that inscribed in the balance sheet, whether through unanticipated risks, a cost of capital increase, or a change to cashflow assumptions, it is expected that those goodwill assets are impaired in the accounts.

Goodwill therefore no longer needs to be amortised (gradually expensed) on an annual basis and is instead subject to periodic impairment assessments. Goodwill therefore forms a larger part of large firm assets on average than they did before the accounting change. Many firms have levered up against that larger asset base; Carillion is not unique in that regard. But levering up against your goodwill is a dangerous inter-temporal gamble. If goodwill is supposed to capture the present value of discounted future cashflows of underlying assets, debt is a claim on the future cashflows of the firm (its liability identity), but also allows firms to bring cash forward into the present (its asset identity) which can then be put to use for a number of purposes. The difficult temporal balancing act for a firm is to make sure that the present costs of its future liabilities can be met from the income generated by its underlying assets. And this is where firms like Carillion come unstuck. It over-estimated the future income generating capacity of its assets (contracts) and this encouraged it to do a number of silly things to keep things going for the stock market and senior management.

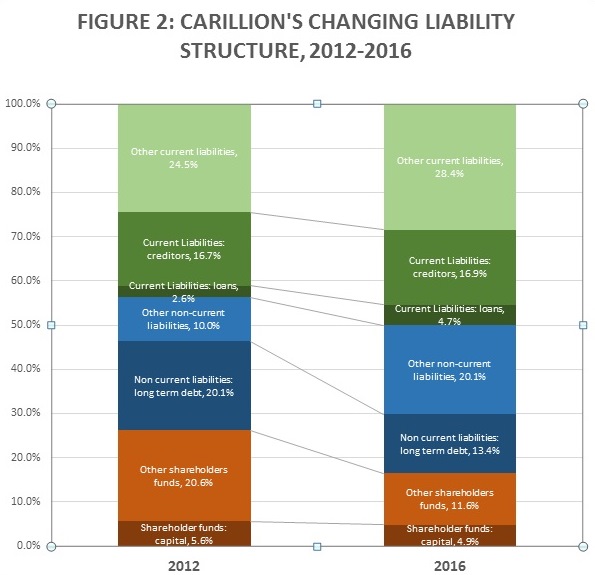

First, Carillion borrowed against its assets (intangible or otherwise) and paid out dividends to placate shareholders and trigger board bonuses: for the period 2012-2016 Carillion paid out £394m in dividends. Although it will not have been audited as such, this looks a lot like a firm paying dividends out of debt – aping the dividend recap practices of the private equity sector. In 2016 for example it paid out more cash in dividends (£78.9m) than it received in net cash flows from operating activities (£73.3m). This ultimately eroded shareholder funds as a percentage of total liabilities, which fell from 26.2% in 2012 to 16.5% in 2016.

Second Carillion took on more short-term liabilities, leading to problems of maturity mismatch. Current liabilities to total liabilities (including shareholder funds) rose from 43.8% in 2012 to 50% in 2016 (Figure 2) – although some of this is accountable for by the erosion of shareholder funds. Third, despite being faced with underperforming contracts, Carillion did not impair its goodwill, but instead tried to grow its way out of a crisis by bidding for more and more new contracts to generate income to pay next year’s creditors, who had lent on an increasingly short-term basis. This sounds suspiciously like a lawful Ponzi scheme, as Matthew Vincent points out. If Robert Peston’s conversation with a cabinet minister are also to be believed, Whitehall officials gave Carillion over £1bn of contracts knowing their financial position was precarious, effectively making taxpayers a kind of Ponzi scheme investor of last resort. With the NHS under serious financial pressure, this largesse towards a company whose chairman is a Tory party advisor and donor is surely a scandal in waiting.

The push to win contracts to pay back its short term creditors led to top line growth but margin collapse. Their Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) margin fell from 5.34% to 4.09% between 2012 and 2016. The recent failure of a number of PFI contracts was the perfect storm and the firm went under.

There are so many lessons to take from the Carillion debacle. For financialization scholars it tells us about the modern financialized firm: the prevailing emphasis on present-ist distributional struggles between workers or investment and shareholders misses the point that these are not zero-sum trade-offs when companies borrow to finance investment or distributions. A more central financialized tendency is for firms to manipulate their balance sheets to play with the temporalities of income and obligation. The primary tension that arises is one between claims made today and those who wish to claim tomorrow; between distributions in the present and the claims of pension fund beneficiaries in the future. Or to put it another way: the firm is a portal (moving income through space and time), collateralised by an activity, working for elite advantage. That advantage includes abusing limited liability privileges to use the firm as a repository for risk that others must bear. The process of levering up against your intangibles to enable payouts is creating ‘go-to-zero risks’ which the state is on the hook for.

Second, this inter-temporal transfer whereby firms lever up against their intangibles and then payout on dividends and buybacks (often with additional tax benefits) is not unique to Carillion. Brexit is ushering an alternate future to that currently inscribed on many firm balance sheets, with all kinds of uncertainties looming about what that means for projected future income streams and the discount rate. We may well see more – potentially many more – collapses of this kind. The propensity for thinly capitalised firms to jettison their pension scheme obligations when they run into trouble should now be a serious governance issue. With the Pension Protection Fund already in deficit to the tune of £103.8 billion, it is not clear how sustainable things will be if many more follow Carillion’s path.

Third, it raises questions about the management of the outsourced state. Firms like Carillion moved into areas where they had no experience or competence. This reveals a tendency within UK senior management circles to value generic, transposable skills around governance structures, risk management processes and performance management systems. This may facilitate the circulation of increasingly well-paid management elites who can simply take their techniques from firm to firm, but does little to improve services, where tacit knowledge and a facility with operations should be prerequisites. The failure of a small number of contracts in unfamiliar areas was always likely to have a disproportionately disruptive effect. And this has devastating consequences for users and workers.

Fourth, it raises serious questions about the viability of the state outsourcing project more broadly. This is discussed in a book on outsourcing I co-authored. Public and private sector are never truly separable when the State assumes the downside when things go wrong, and companies seem increasingly willing to exploit that moral hazard. But Carillion raises special concerns about the networks that accrete around serial contract winning firms. This is not just about the relation between the Conservative Party and Carillion, but also the role of KPMG, Carillion’s auditor. In its 2016 accounts it is difficult to understand why the company did not impair its goodwill to signal to investors and creditors that its cashflow situation was deteriorating. Did KPMG believe that there were viable plans for the firm to grow its way out of its predicament? Were KPMG briefed about potential new contracts the firm might win? If they were, then the question is not the fuzzy boundaries between the state and outsourcing companies, but about the very purpose of this form of outsourcing: is it for outsourcing firms to help the state with its service delivery problems, or is it for the state to help capital with its profitability problems?

This article was originally published at SPERI Comment.