The government’s got Britain caught in an exchange rate trap

Image: BBC.

The collapse of the foreign exchange rate since the BREXIT referendum is on a scale we have not seen in many years and yet the government seems totally unconcerned. Indeed in large part the fall in the rate of exchange is directly the result of statements and actions taken by the government. Some decline in the rate was predicted following the referendum, but it seems now to be in free-fall as a result of recent declarations by a government that it is intent on what it calls a ‘hard BREXIT’. No one, least of all the government, has a clue what sort of trading arrangements are feasible and attainable in a world of managed trade and within the WTO framework. At the present time at least 44% of all UK trade is with the EU and it seems highly unlikely that access to this market can be retained unless the UK accepts free movement of labour.

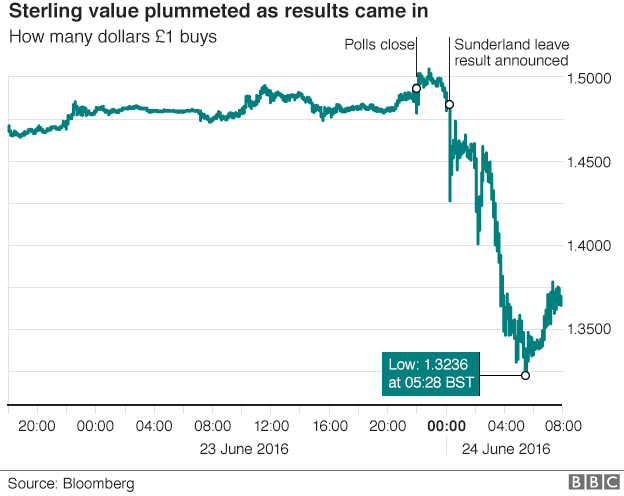

So it is unsurprising that, in these conditions of uncertainty, the exchange rate has collapsed. But the scale of the decline in the exchange rate has been greater than anyone had predicted. Sterling has fallen sharply against the US dollar to a rate not seen since the 1980s and there have been similarly sharp falls against the euro. In the case of the dollar and the euro there are now predictions that the rates may fall to parity within the next few months with huge implications for the British economy and for general living standards.

The overall effect of exchange depreciation on this scale is to reduce real national income – the cost of imports is increased and export prices are lowered. In the short run also the current account will worsen since the cost of imports rises and any growth in export volumes will depend on conditions in foreign markets and on the ability to increase UK productive capacity. But the government seems unperturbed both by the scale of the exchange rate decline and by the potential economic costs that will inevitably follow. It is worth noting that the Treasury assessment of the costs of BREXIT made prior to the referendum predicted a decline of between 5.4% and 9.5% of GDP over 15 years, and losses of revenue per annum of between £38b and £66b over the same period of time because the tax base would be much smaller.

Government having largely created the conditions under which the exchange rate has collapsed now has more or less no instruments of economic policy available with which to reverse the decline and seems totally fazed about what to do. Since the end of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in the early 1970s the world has operated under conditions of variable rates which have fluctuated in accordance with market conditions – the latter have in general reflected fundamental economic conditions in different countries. Countries with dynamic and competitive conditions have experienced strong balance of payments positions and other less successful countries the opposite with associated high levels of international debt. Germany is a good example of a country with a strong balance of payments and while one might have expected the exchange rate of Germany to appreciate this in fact has not happened because the Eurozone is a system of fixed exchange rates. Exchange rates have thus been prevented from playing their appropriate role within the Eurozone with very undesirable effects.

The UK very sensibly refused under Blair/Brown to join the Eurozone and sterling has floated against all other countries globally with the exchange rate being permitted to play more or less its appropriate role in the conduct of economic policy. Of course what we have experienced globally, including the UK, has been a system not of freely floating rates but one of managed rates where countries have used instruments of monetary policy to influence the level of their exchange rate so as to achieve competitive advantages. Thus countries could use exchange controls so as to influence capital movements or levels of domestic interest rates as ways of attracting capital. In recent years, for example, Switzerland has levied negative interest rates on bank deposits as a way of deterring capital inflow and thus damping to some degree the appreciation of the Swiss currency. Japan has similarly set domestic interest rates at levels to reduce appreciation of the yen. One of the costs of the Eurozone for members is that individual countries do not have control of the level of interest rates which are set by the European Central Bank and these may be totally inappropriate for individual countries such as Greece or also Italy which have large fiscal deficits.

The UK has for many years been running a deficit on its current account of the balance of payments. In other words there has been a large excess of imports of goods and services over what is exported. In the second quarter of 2016 the current account deficit was no less than 5.9% of GDP and deficits of this sort of scale have been common for many years. Of course a country can only continue to run a large current account deficit if it either has large foreign exchange reserves which the UK does not have [indeed it has been engaged in reducing their level as a means of financing domestic fiscal deficits under the previous Chancellor Osborne] or else it borrows extensively overseas.

And herein lies the first of the problems facing the government. How to generate the conditions favourable to continued foreign capital inflow so as to finance the huge current account deficit and at the same time have low domestic interest rates, with the value of sterling in free fall. The Bank of England in August reduced its key short term interest rate to 0.25% in an attempt to sustain domestic demand in response to the uncertainty released by the Brexit referendum. But low interest rates act as a deterrent to foreign capital inflow and are unlikely to do much to sustain domestic demand. Foreign capital will of course see opportunities to buy British financial and non-financial assets since the sterling cost has fallen as a result of the exchange rate depreciation but similarly their foreign exchange value will be lessened as and when they attempt to liquidate these investments. For any investor it would pay to hold off buying sterling assets until the exchange rate has stopped falling, and it looks as if it will not do so until later in 2017 when it may be clearer what BREXIT means for the British economy.

The Bank (and Government) could reverse its current interest rate strategy (low rates to sustain domestic demand) but any significant rise would create chaos given the level of secured (mortgage) and unsecured debt much of it unfinaceable if rates were to rise. To finance the current account deficit through encouraging capital inflows through higher interest rates would add to the domestic deflationary pressures already caused by the threat of Brexit and thus causing higher levels of unemployment and widening the fiscal deficit as automatic fiscal stabilisers kick in. As output contracts tax receipts fall and higher levels of unemployment generate more government expenditure on welfare and other payments. It would also create chaos in the housing market because it would generate widespread negative equity.

What to do in situations of policy conflict such as this? Well the government story repeated ad nauseam by ministers who seem to understand nothing about economics is that the fall in the exchange rate will boost demand through encouraging exports. Now to a degree this may indeed happen – but with long lags and the scale of any general increase in demand is highly uncertain and probably not very large. Exports currently account for some 28% of GDP and since manufacturing output in the UK is now less than 15% of GDP the leverage that is possible through an expansion of the component of demand that is considered sensitive to a falling exchange rate is relatively small. Plus, and this is very important, there is a very significant import content of exports – estimated by OECD as 23%. A large part of both UK manufacturing output and especially of exports is through chains of inputs that are highly specialised and not easily substitutable from other suppliers. So as the exchange rate depreciates so also does the cost of inputs rise for both domestic markets and for exports – as we have seen for the latter by almost a quarter. So a significant part of the competitive gain to exporters from the fall in the exchange rate of sterling is offset directly by the rising cost of imports that are key inputs in production.

There will also be indirect effects on the cost of exports which derive from domestic cost adjustments as the impact of the decline in the exchange rate feed through into the economy. Imports are 30% of GDP and a fall of, say, 15% in the sterling exchange rate will add something like 5% to domestic costs of all food and other commodities, including fuel where increases in petrol and diesel prices have already been announced by suppliers. Oil prices are set internationally in US$ so the fall in sterling against the $ immediately causes an increase in the price of fuel in sterling terms.

The UK is now as a result of globalisation very dependent on foreign supply of many industrial products with few alternative domestic sources and their costs will inevitably increase. The exchange depreciation that has already occurred will raise domestic costs of production and add directly to prices of more or less everything. There will thus be an impact on domestic cost and price levels and a fall in domestic disposable incomes. This will have multiplier effects on domestic demand and lead to further rounds of output contraction. How wages and incomes will react is uncertain but pressure on disposable incomes and rising unemployment is bound to be resisted across all sectors of the economy.

There are other features of the situation that are worth noting in part because they are longer term in their origin and undermine the government’s strategy [if one can call it that]. If there is to be a rise in net exports (a fall in imports and an increase in exports caused by the fall in the sterling exchange rate) then UK output has to become more competitive. But as we have seen the current account of the balance of payments has been in large deficit for many years and this reflects the general uncompetitiveness of the economy. The exception to this statement is the financial services sector (more on this below) but otherwise the UK has displayed low levels of international competitiveness. This reflects the low level of productive investment and a total disregard by government and private industry of the skills of the domestic workforce.

The ONS has just published data on comparative labour productivity which makes only too clear the gap between UK and its main competitors. In 2014 output per hour worked in Italy was 10% more, in the USA and France 30% more, in Germany 36% more than in the UK. For the G7 countries the average productivity level was 18% more than the UK. This gap reflects low levels of investment per worker in the UK, low levels of investment in skills and especially low levels of Research and Development expenditure. In the case of the latter the UK spends 1.7% of GDP whereas Germany spends 2.9% and the US 2.7% (for the EU of 28 countries the average level is 1.95%). The UK for example trails the USA in productivity per worker in all sectors according to the ONS and especially in manufacturing. So how is the UK supposed to take advantage of a change in the financial exchange rate given these underlying factors which ultimately determine international competiveness?

Of course one of the factors that has made it possible for the economy to function more or less effectively has been the ability to draw on the international market for skills. This reflects the abject failure of governments over many years to invest in education and training. There are key sectors which are totally dependent on recruitment of overseas labour including health and social care, financial services, higher education and basic scientific research, construction and transport. It takes many years to train people and ensure their appropriate experience and yet government has said that it will restrict immigration irrespective of the needs of different productive sectors as part of its hard Brexit policies. It is unsurprising in these conditions and also facing the uncertainty of levels and instability of exchange rates that businesses have declared their opposition to the government’s stand on Brexit.

The UK has become since it joined the EU in the 1970s an important destination for direct investment less because of the opportunities opened in the UK market and more because it was a base for exporting to the rest of the EU. The EU is now the largest market worldwide and yet the hard BREXIT stance of Government threatens access to the single market. British producers will, if BREXIT is implemented as planned by the Government, face the common external tariff which will make it more expensive to sell against competitors inside the EU. The tariff is substantial – intended to be protective – and will further erode any advantage a fall in the sterling exchange rate gives to British located producers.

The tariff plus the rise in the import costs noted above (and any consequent rise in UK costs such as wages) will erode a large part of any exchange rate benefit to UK based producers. It is unsurprising in these circumstances that a major car producer such as Nissan which sends most of its output to the EU has indicated that all investment is on hold until such times as the present uncertainty of exchange rates and access to the EU market are resolved. Fuji with a labour force in the UK of 14,000 has also voiced its dismay with the proposed exit from the EU. These are among many companies who have located in the UK to benefit from being inside the EU tariff system who will now be having second thoughts on location and levels of production. In the process investment will be cut back and new direct investment flows be reduced so worsening the overall balance of payments.

The key dynamic sector for both employment growth and as a share of GDP for many years has been financial services. These now account for some 10% of GDP and are a major source of tax revenue for the government. The growth of this sector has been largely determined by privileged access to the EU market together with extremely weak supervision by the British banking authorities. It seems evident from statements made by the EU that the current access to the EU under the so called ‘EU passport’ for British financial firms will be discontinued and that the particular locational advantages of being in UK will disappear. This is analogous to the point made in the last paragraph about firms locating in the UK so as to have access to the single market. Again some banks have already indicated that they will relocate to Frankfurt or Paris if a hard Brexit is pursued, and this will reduce substantially exports of services and thus add to the current account deficit of the balance of payments. It will also of course lead to a loss of jobs and reduced payments of taxes to the Treasury so adding to the fiscal deficit.

Why are we in this mess?

This is the $64,000 question and there doesn’t seem to be any simple answer. The instability of the exchange rate and the scale of the fall are creating major problems for all producers – and consumers as well. The government seems oblivious to the costs of its policy both now and in the medium to long term. Its own internal Treasury estimate of the costs for output and employment and to the public finances are unfortunately only too realistic – if anything they underestimate the size of the problems facing the UK. There are clear conflicts of economic policy since interest rates have to be focused on the state of domestic demand/output and cannot be used for managing the exchange rate. In these circumstances and given the totally unrealistic policy on foreign trade it is inevitable that the sterling rate will depreciate and go on falling against other currencies. There are no benefits to be derived from such a drastic decline in the exchange rate as we have witnessed recently since any adjustment of domestic cost conditions so as to increase net exports will take many years to create.

The changes in economic policy that are needed are self evident; a clear statement that the UK will remain in the single market with all that that implies. There is undoubtedly scope for management of labour flows into the UK that will meet EU regulations and these need to be explored. Many EU countries in practice have regulations relating to employment and residence that effectively restrain the flow of migrants and these seem perfectly consistent with access to the single market. Drawing on international skills is critical to the performance of the economy and should be encouraged. Reducing exchange rate instability will be critical to inducing capital inflows and making the UK a destination for productive direct investment. Uncertainty needs to be reduced and confidence again created in the British economy. Domestic investment needs to be increased – both public and private – and a real effort made to create a larger pool of skilled and educated labour.

Whether the current government understands the depth of the problems it has largely self-created is uncertain. And whether it has the courage and foresight to reverse its present policies is a great unknown. One would like to be positive but this might be a level of optimism too great.