Trump, Trade & War: the urgent need for a progressive trade policy

Container Ships, San Francisco bay. Wikimedia Commons.

Donald Trump’s latest Executive Order, issued last week, could foreshadow a dangerous trade war with China and the European Union. It suggests that the nationalists in his administration have got the upper hand for now, and their ideology – for all of their bashing big trade deals like NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) – is no more conducive to a fairer or more peaceful world than the neoliberals they replace. Far from it.

Trade is an issue on which Trump’s cabinet is particularly divided. Unfortunately, neither side in this battle is worth rooting for.

The neoliberals vs the nationalists

Gary Cohen, Wikimedia

In one corner is Trump’s economic advisor Gary Cohn, an investment banker and former president of Goldman Sachs. Cohn got a $284million severance package to join Trump, and has a reputation for aggressive, risky behaviour. Also in Cohn’s corner is Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin – Goldman partner and hedge fund founder.

Both are keen to remove Obama’s post-crash financial regulation and slash corporate taxes, policies which have helped their former corporation’s share price rally to the point that the Financial Times describes as “embarrassing.” Cohn and Mnuchin are the neoliberals we’ve got used to – they want free trade, free markets and an easy life for their corporate friends.

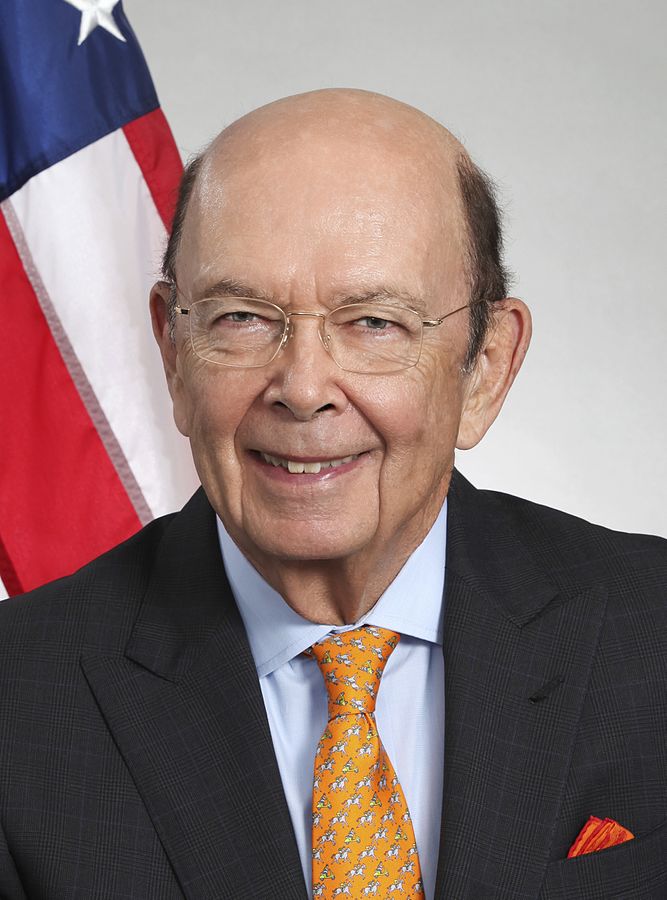

How do you lose a popularity war with these guys? Well, in the other corner stands Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross. Ross is a billionaire investor known as the ‘bankruptcy king’, because of his aggressive asset-stripping strategy – buying up failing companies and selling them on without regard for jobs, pensions or safety standards. Ross was fined in 2016 for breaking financial regulations and his company sued for negligence when, in 2006, 12 miners died in an explosion. He made millions during the financial crisis, both from mortgage foreclosures and bank bailouts. In Ross’s corner is Peter Navarro, at the National Trade Council, author of ‘The Coming China Wars’ and ‘Death by China’.

Wilber Ross, Wikimedia

These charmers are the economic nationalists, and they want to rip up international trade rules which they see as preventing the US from negotiating more exploitative trade deals. They hate NAFTA not because two million Mexican farmers losing their livelihoods was too much pain, but because it wasn’t enough. Their policies border on the fascist, protecting US industry, raising tariffs, then throwing their subsidised goods into foreign economies to export their economic problems somewhere else. It’s the sort of stuff that, in the 1930s, led to real war.

These economic nationalists have an obsession with the US trade deficit which ‘proves’, in their minds, that other countries must be cheating. So rip up the rules, and let the bully rule supreme. In their sights are China and the European Union – the US’s two biggest competitors who need to be taken down a peg or two. If this faction hold sway, expect retaliatory trade measures to follow Trump’s executive order.

How we respond

The contradictions in Trump’s cabinet are also at the heart of Brexit Britain. On the one hand, Theresa May’s government is filled with free traders. Liam Fox and Boris Johnson are like men who have recently awoken to find the last 150 years were a bad dream, and they’re running the empire at the height of its power. They are egged on by think tanks who believe, for example, we don’t need farmers any more – Africa can grow our food for us and grow it much cheaper.

On the other hand, Brexit largely appears to be a vote for protectionism. The Sun can’t contain its excitement at slapping punitive tariffs on the EU, while many people from communities that have suffered the full brunt of neoliberalism hardly voted for a more competitive environment.

Underlying these different perspectives are deep ideological differences about how the world works. The neoliberals believe that in international trade, everyone’s a winner. It creates such growth and opportunities, that even someone who loses their job as a result of freer trade will quickly find a new one, and anyway prices in the shops will become cheaper. So what’s not to like?

The nationalists tend to think that trade is a zero sum game – what one side gains, the other loses. This accords far more with the ‘common view’ of the economy as a household, hence the hostility to immigrants who are laying claim to a limited number of jobs. They believe in using forms of protectionist measure like tariffs to get ‘one up’ on their competitors.

Both stories are untrue. More and more people accept that trade has losers as well as winners – and over the last 40 years the losers have essentially been left to fend for themselves, hence the backlash against neoliberalism. At the same time, the economy is definitely not a household. Capitalism is an extremely dynamic system, and trade can create new economic relationships which spur growth, jobs, new industries and more.

These divisions should give the left the perfect opportunity to expose the contradictions in the new establishment’s economic policy. Yet to date, the left has watched this battle unfolding, unable to offer a distinctive alternative which could resonate with a broad mass of people. The neoliberals created this immense crisis which is now unfolding at a terrifying speed. But the nationalists will ensure that that crisis ends in the most brutal way possible.

What does a left trade strategy look like?

For the left, the starting point must be that trade is about power. This should be obvious for a country which made its wealth trading enslaved people, decimating one of the richest economies in the world (India) and forcing opium on China with gunboats.

In the modern world, totally ‘free trade’ without government regulation to control the free movement of capital or to help restructure an economy to meet people’s needs, is likely to create massive inequality, and hand corporations huge power over governments. But on the other hand, protecting industry that is corrupt or desperately inefficient isn’t likely to be beneficial to wider society, and dumping protected goods on other societies simply displaces economic problems, often leading to conflict.

In the 1950s and 60s trade was relatively controlled and regulated, and the benefits were more fairly distributed – at least across western society. In the modern economy, having given away that control, nation states are left powerless before the might of corporations. Social democracy’s capitulation to neoliberal economics is one expression of this and leaves us bereft of a thought-out progressive international trade policy.

So how to move forward? A portion of the left would like to return to the economy of the 1960s, but even if possible, the dislocation this would cause would be catastrophic. And unless everyone moved together, corporations would end up with far greater power over individual nation states, as they are forced to compete for capital. This is what Britain faces post-Brexit.

A better strategy, especially for those who understand the long-term limitations of the nation state and the positive benefits of certain types of economic integration, is surely to push for stronger social and democratic elements to that integration, allowing citizen control of economic direction. For all it’s faults, and they are huge, the EU is the world’s biggest trade bloc to develop social and democratic elements that actually meant many standards increased.

Developing countries could often benefit from doing the same – regional integration with strong social and democratic dimensions to break the stranglehold the global north still enjoys over the global south.

Within such blocs, we can begin to develop alternative rules for the way we trade. In fact, the EU could start taking a lead right now. The first step is to ensure no trade deals trumps human rights, climate commitments or a basic level of food security – that should be enforceable in individual deals. We also need to write in strong commitments to exclude public services, government procurement and a right to regulate that cannot be challenged by international ‘investors’ through the sort of toxic ‘corporate court’ system which currently exist in too many trade deals.

These corporate courts need to be scrapped, and replaced with mechanisms that allow individual citizens whose rights are impinged by foreign corporations to achieve restitution – if necessary at an international level. And, on a more ambitious level, we could give special trade preferences to goods made in exemplary conditions, or – even better – produced in cooperatives or collectives.

We get a glimpse of what an alternative trade system might look like from the ‘pink tide’ governments in Latin America which developed a fledgling alternative trade system known as ALBA, specifically based on principles of solidarity, redistribution of wealth, and cooperation. Venezuela’s oil-for-doctors programme is one small example, and even Livingstone’s London got in on the act with cheaper fuel to power public transport. The potential for an international solidarity economy is huge, and well crafted trade rules can help bring this about. In so doing, we also fight xenophobia and insularity.

There is significant work to do to develop these models, and just as much work in building alliances which can convey this to an increasingly insular public. When people’s experience of globalisation is simply unemployment, commodification and marginalisation, it’s easy to jump on the sort of nationalist agenda represented by Wilbur Ross, especially when it depicts itself as anti-establishment.

Our task is to develop economic models which are open, international, collaborative and local and democratic. This can help us overcome the ‘neoliberal or protectionist’ ‘choice’ on offer, and it allows us to develop a clear and compelling vision for international economics that taps into the concerns of those who voted for Trump or Brexit out of desperation, while preserving the internationalist outlook of those on the left who despise both. Such models are the only hope we have of preventing a further decline into nationalism, based on a fear of the foreigner.