There is a magic money tree – don’t let politicians tell you otherwise

£’s. Petras Gagilas / Flickr. Some rights reserved.

Few aspects of our economy are as poorly understood among politicians and the general public as our monetary system. This becomes particularly obvious – and dangerous – during general election campaigns.

Last night Theresa May responded to a nurse’s concerns over pay in the NHS by saying “there is no magic money tree” to provide “everything that people want”. Other Conservative politicians have used the same line to attack Labour’s plans to increase public spending.

It’s an old trope. The argument goes like this: the UK has lived beyond its means for too long. The national debt now stands at an eye watering £1.7 trillion, meaning that we have saddled future generations with unsustainable debt and interest payments. We simply can’t go on spending money that we don’t have. Money doesn’t grow on trees – duh!

The only responsible course of action, the story goes, is to rein in spending and make “difficult choices”. Free school meals? Not anymore. Those new homes that we were promised? Forget about them. Investing in the technologies of the future? Don’t be so irresponsible. Upgrading creaking infrastructure? Come off it.

This narrative is incredibly powerful, as it chimes with peoples’ experience of managing a household budget. But in the context of a national government, it is almost entirely wrong.

It is true that the national debt stands at £1.7 trillion, or around 87% of GDP. But this is not particularly high by historical standards – after the Second World War the national debt stood at 243%. Imagine if Clement Attlee had listened to those who insisted that this meant Britain had to cut back public services. There would be no NHS, and no welfare state. Britain would be a very different place.

But despite its ominous reputation, the national debt is not all that it seems. The national debt is simply the sum total of all the government’s IOUs – the promises it has made to pay money back in future, plus an agreed amount of interest. Unlike a household, the UK government has its own central bank and its own sovereign currency. This means that the government borrows and spends in a currency that it controls. Here’s where things get interesting.

Since 2009 the Bank of England has purchased £453 billion of government debt from the private sector through a process called ‘quantitative easing’ (QE). Put simply, QE is the technical name for what happens when a central bank creates new electronic money and uses it to purchase assets from financial institutions.

Yes, that’s right – newly created money. Alas, the magic money tree does exist!

As a result, over a quarter of the total national debt is now owed to the Bank of England. But hold on, who owns the Bank of England? Well, the UK government does.

To put it another way, the UK government owes £453 billion to itself. This raises the obvious question of whether it really exists at all. As Jim Leaviss, a bond investor for M&G Investments recently remarked to the Financial Times: “Is there any difference in it being in a musty old drawer in the Bank of England, or saying it doesn’t really exist?”

Confused? Bear with me – things get a little more confusing yet. When a government borrows money it has to repay the principal amount that it borrowed plus interest. In the UK, around £50 billion of the annual government budget currently goes towards interest payments. Because of QE, the government has to pay interest to the Bank of England on the £453 billion of government bonds that it holds.

But in late 2012 George Osborne announced that the interest payments that the Bank of England receives from the government will be remitted back to HM Treasury to help pay off the national debt. Since then the Bank of England has transferred £62 billion – money that it received as interest on bonds purchased with newly created money – back to the government. So thanks to QE, the government isn’t paying any interest at all on over a quarter of the national debt. Talk about funny money!

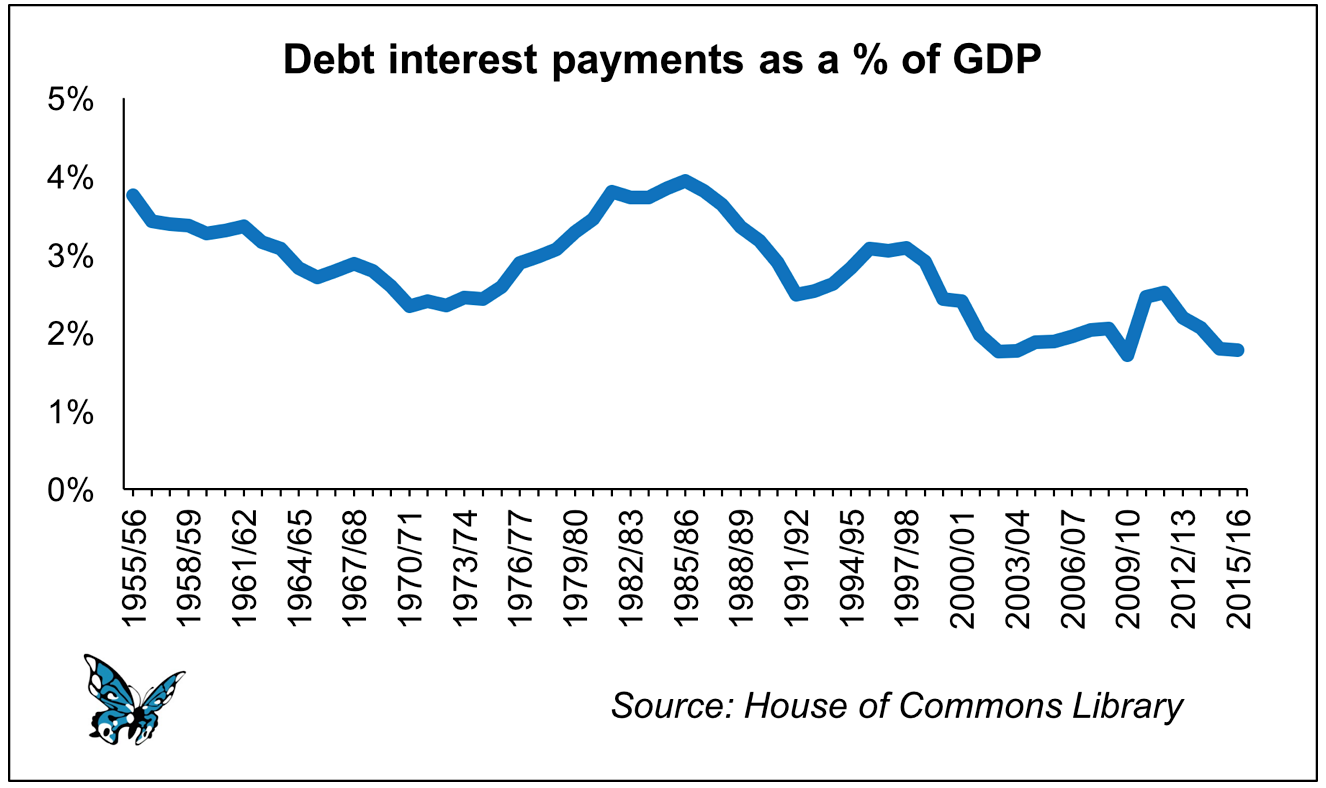

The result is that today the government spends less on interest payments than at any point in history. The national debt has never been so affordable.

You may have noticed that issues of “affordability” never arise when the proposed spending relates to activities like going to war or bailing out the banks. That’s because for a country like the UK which has its own central bank and borrows in its own currency, financing government spending is never a problem. The “magic money tree” attack is simply a convenient way to mask an ideological crusade to shrink the state.

This does not mean that governments can spend without limit, or that governments should spend money unwisely. Government spending has consequences for inflation, employment, capital formation and many other things. Sustained over-spending can have serious consequences.

But right now the UK economy is crying out for public investment. From addressing climate and demographic change, to tackling inequality and the housing crisis, the UK’s long-term prosperity depends on having a government that is willing to direct investment into the areas of the economy most in need.

Don’t let politicians tell you otherwise.