Can the new metro mayor transform the West Midlands economy?

Andy Street. BBC/Screengrab. Some rights reserved

Minutes before the West Midlands metro mayoral election result on May 5, Green Party candidate James Burn responds sharply to my suggestion that the campaign he has just fought had been more consensual than other present-day political battles: “There were key disagreements about economic plans!”

The election was won by Conservative candidate and former John Lewis managing director Andy Street, who saw off rivals by a mere 3,766 votes. He issued a green-coloured manifesto rooted in bread-and-butter jobs and skills issues, and played up his Birmingham and Solihull upbringing on the campaign trail. Burn contends this glossed over his underlying message of trickle down prosperity from booming industries and new construction.

“If you look at Sheffield City Region, we’ve seen significant growth but it’s not been shared. Or in Barking, there’s great transport links to a massive new development, but the development has not economically benefitted Barking or significantly changed poverty levels. The West Midlands is at the bottom of the table for most indexes of deprivation. We need a very different approach.”

When Street suggests a leading role for the West Midlands in UK industrial strategy, or innovative new approaches to public service delivery, Burn accuses him of a naïve faith that central government makes evidence-based, rather than ideological decisions. His ambitions for an improved public transport network, Burn says, are pole-axed by the rail companies being locked into contracts, the government’s Bus Services Bill which rules out new municipal bus companies, and Transport for West Midlands lacking the money to carry out the franchising exercise Street wants to undertake.

Not everyone agrees. Community activist and former council housing officer Desmond Jaddoo, who interviewed all six candidates, praises Street for being “crystal clear” about the mayor’s powers, while his rivals wanted to veer off into wilder political waters. Being a high street store boss gives him an advantage, Jaddoo suggests, when it comes to proposing technocratic convincing solutions against the background, in Birmingham at least, of a long underperforming local authority.

“We needed an independent lead who has cross sector experience and more importantly, proven impact” says Birmingham-born serial entrepreneur and diversity champion Joel Blake, who looks forward to a greater fusion of private and public sector thinking and shared resourcing under Street and the West Midlands Combined Authority.

Other analyses would point to other factors: the degree that Street outspent other candidates against the spirit of campaign limits, the mixed local reputation of Labour contender Sion Simon and discomfort with his party leadership, and the loyalty that John Lewis inspires as a West Midlands employer. Simon Jeffrey of the Centre for Cities think tank believes that ideological differences take a back seat in urban leadership, recalling 1930s New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s “no Democratic or Republican way to take out the garbage” quip.

Andrew Stevens of citymayors.com sees Street as both a partisan Conservative central to Number 10’s plans for further regional devolution, and “a very emollient quiet operator” as the chair of the Greater Birmingham and Solihull Local Enterprise Partnership. Rebecca Riley of Birmingham University remarks that with the calibre of runners-up – including an ex-MP and serving MEP, the leader of the opposition group on Solihull council and a former CBI regional director – “it’s a shame we didn’t get more of a debate and that we can’t do more with them as a region”.

Black Country: from employment black spot to in the black

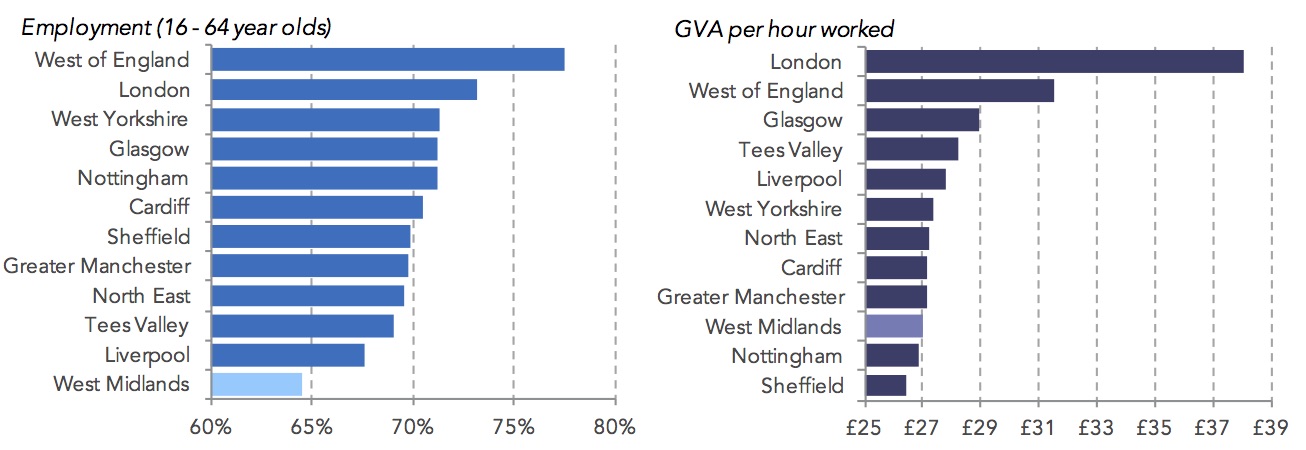

In a 2016 report, the Resolution Foundation pinpointed the West Midlands’ economic challenges – the lowest employment rate of any UK city region at 64.5%, and the slowest recovery in employment prospects after the financial crisis (half the average for conurbations). Average household income post-housing costs is the lowest in any of Britain’s city regions. Chronic and severe skills shortages hold back productivity growth as measured by GVA per hour worked.

Charts produced by the Resolution Foundation

In late 2015, eight out of nine manufacturers reported to the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce that they faced hiring problems. 16.3% of residents have no formal qualifications and only 28% have a degree, compared with 37% nationally. Rebecca Riley outlines the supply and demand mismatch: a long line of older workers without advanced technical qualifications who aren’t reskilling, migrants arriving who may be highly skilled but not with UK-recognised qualifications, and limited graduate retention, despite the highest per head student population of any region. Areas like Wolverhampton have structural skills gaps going back generations.

Street’s ambitions to make wage growth the fastest in the UK, a zero youth unemployment target, and a string of initiatives – from a “West Midlands First” graduate programme to an All Age Careers Service – align closely with the Resolution Foundation’s skills and jobs priorities. His manifesto emphasis on boosting tech, creative, life sciences, professional services, construction and green jobs also addresses think tanks’ calls to champion growth potential across the West Midlands’ diverse economy, beyond the car industry and other manufacturing.

However, there is a far bigger economic challenge for the metro mayor than this, as Street acknowledged when he told the Birmingham Mail that the competition is Berlin and Barcelona, not Liverpool and Manchester. The region has scored a striking success with 50% export growth since 2008 – “quite phenomenal for a mature economy”, says Black Country-based economist Paul Forrest. Along with the North-East, it functions as a dynamic standalone economy in the global supply chain, giving it a key role in an export-led, globally trading vision for the UK post-Brexit. Meanwhile output, Forrest argues, has been damagingly underestimated by statistical practices, such as attributing some manufacturing firms’ output figures to their London HQs. Local Conservatives’ claims of a £16 billion productivity gap on the basis of £20,137 output per resident fail to square with separate calculations of almost £45,000 output per worker, said think tank IDEA Birmingham in 2015.

“We are owed billions”, says the Lib Dems’ Beverley Nielsen, who welcomes the £1.1 billion devolution deal over the next 30 years but insists that it does not detract from decades of underinvestment, or the massive cuts in public services now being exacted. With 80% of rail freight and 30% of the nation’s road freight passing through the Midlands, 45% of the UK’s exports to China coming from the West Midlands, 30% of UK automotive manufacturing and 3% of the world’s aerospace industry located there, Nielsen argues that her region is the heartland of the UK economy, and should be treated as such. She worries about a Brexit double whammy through the impact on supply chains and exports. She laments the lack of serious thinking about how to access substitute markets such as India and, for all the talk of industrial strategy, about how to protect regional economies.

Top down or bottom up?

Directly elected mayors have been energetically championed in the UK since Tony Blair’s government introduced them. Simon Jeffrey of Centre for Cities argues that the individualization of policy and accountability yields dividends locally and for the rest of us: “Getting Birmingham close to average productivity would move the needle on national aggregate performance, as well as doing so much for the people of Birmingham”. While Andy Street’s executive power is constitutionally limited, Jeffrey concedes, he enjoys a “bully pulpit” that foot-dragging local councillors and national politicians will find hard to ignore, and will be able to galvanise schools and academies over skills, for example.

Jeffrey admits to the “anathema”, for many voters, of having yet another politician on the scene – the city of Birmingham voted against an elected mayor in 2012 – but points to the historic lack of collaborative working between West Midlands local authorities and the huge strides made to address this in just a few years. Andrew Stevens of citymayors.com says the lack of a mayoral scrutiny function was an oversight and may soon be remedied.

For others, it is more the notion of a top-down development agenda which is anathema. Karen Leach of Localise West Midlands says that the metro mayor is “part of this macho individualistic emphasis on big and shiny. We’re going to have faster trains and bigger buildings! It’s deeply frustrating”. Questioning the emphasis on foreign direct investment investment by Street and the region’s business and political leadership, she points to Localise’s 2013 research literature review, which found community economies delivering better on job creation, resilience, stability and economic returns compared to a centralised approach. She thinks the skills debate is mistaken by failing to anticipate companies’ needs in future, and by falling into a crudely reductive approach of matching deprived community A with company B rather than putting humans at the heart of policy-thinking.

Localise is working on a report with New Economics Foundation looking at social care as an economic sector bringing value to communities, rather than as a service to deal with a social problem. Leach argues that serious investment in the sector would generate returns to the regional economy which would compare favourably to billions being poured into the car industry or HS2,.

“We’ve been known as a city of a thousand trades in the past, and I’d like for us to become a city of a thousand SME clusters” Birmingham City Council leader John Clancy said last year. In the metro mayor race, Beverley Nielsen called for platforms for in-region investment – a West Midlands regional bank, £1 billion innovation fund and Chamber for Business Growth – and suggests FDI is better directed into supporting local businesses through on-shoring supply chains than in the form of headline-grabbing mammoth projects.

The scale of funding in the UK for start-ups and scale-ups is dwarfed by that in California and Germany. Rather than put £100 million into self-driving vehicles, Nielsen asks, why isn’t the government dedicating billions in innovation funding for the likes of Dudley-based Westfield Sportscars, whose experimental autonomous POD has done half a million miles more than Google’s driverless car? Her other priorities include getting university innovation closer to market and offering meaningful business support by getting companies like Jaguar Land Rover and engineers GKN sharing expertise with SMEs. “We need more ambition in our economy – we’ve got talent, we’ve got the people” she says.

Towards a sharing and caring economy

The opening of a new chapter for the West Midlands presents an exciting opportunity for economic experiment, such as the pilot of Universal Basic Income (UBI) that the trade union Unison called for in its mayoral election manifesto. Becca Kirkpatrick, chair of Unison West Midlands community workers’ branch, describes UBI as “recognition that at this point of history it is not right that some are going without”. It would enable people to study or reskill and figure out what kind of work they really wanted to do, she says. “It provides a safety net for innovation”, James Burn argues, pointing to the wasted potential of much smaller numbers of BME and female West Midlanders than white males starting their own businesses.

Filmmaker and campaigner Paul Stringer would like to see UBI in combination with a “West Midlands Pound”, on the model of the Bristol Pound, payable for local government services and at participating independent shops to keep more money in the regional economy. In the mayoral campaign, Sion Simon and James Burn committed themselves to a UBI trial while Nielsen, Street and UKIP candidate Pete Durnell expressed some degree of interest. (On the Living Wage, Street says his retail experience has shown him it isn’t the best way to deliver prosperity).

In his first weeks in the job, Street has struck an inclusive tone, setting up hot desk offices in Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Coventry and making a commitment to eliminate rough sleeping, while at the same time saying he will pursue the “economic feelgood factor” by lobbying for the Commonwealth Games and Channel 4 to come to the region. But how relevant is his upbeat, growth-driven vision to those at the bottom: the increasing number of residents using food banks, the one in three children growing up in poverty and the children of refugees who are starved of training opportunities, jobs and youth provision? How much room will the John Lewis mayor allow for co-operative and collaborative economic thinking?

Street won the election with 50.4% of the vote to Sion Simon’s 49.6%, but perhaps the key figure is voter turnout at 26.7% - more than expected, less than the 30% Street described as “credible” during the campaign. A successful economic policy will mean engaging with many more people of the West Midlands before the next vote comes around in 2020.