Why the distribution of wealth has more to do with power than productivity

Image: Glenn Halog, CC BY-NC 2.0

According to a new OECD working paper, Britain is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Net wealth is estimated to stand at around $500,000 per household – more than double the equivalent figure in Germany, and triple that in the Netherlands. Only Luxembourg and the USA are wealthier among OECD countries.

On one level, this isn’t too surprising – Britain has long been a wealthy country. But in recent decades Britain’s economic performance has been poor. Decades of economic mismanagement have left the UK lagging far behind other advanced economies. British workers are now 29% less productive than workers in France, and 35% less than in Germany. How can this discrepancy between high levels of wealth and low levels of productivity be explained?

The process of how wealth is accumulated has been subject of much debate throughout history. If you pick up an economics textbook today, you’ll probably encounter a narrative similar to the following: wealth is created when entrepreneurs combine the factors of production – land, labour and capital – to create something more valuable than the raw inputs. Some of this surplus may be saved, increasing the stock of wealth, while the rest is reinvested in the production process to create more wealth.

How the fruits of wealth creation should be divided between capital, land and labour has been subject of considerable debate throughout history. In 1817, the economist David Ricardo described this as “the principal problem in political economy”.

Nowadays, however, this debate attracts much less attention. That’s because modern economic theory has developed an answer to this problem, called ‘marginal productivity theory’. This theory, developed at the end of the 19th century by the American economist John Bates Clark, states that each factor of production is rewarded in line with its contribution to production. Marginal productivity theory describes a world where, so long as there is sufficient competition and free markets, all will receive their just rewards in relation to their true contribution to society. There is, in Milton Friedman’s famous terms, “no such thing as a free lunch”.

The aim was to develop a theory of distribution that was based on scientific ‘natural laws’, free from political or ethical considerations. As Bates Clark wrote in his seminal book, ‘The Distribution of Wealth’:

“[i]t is the purpose of this work to show that the distribution of income to society is controlled by a natural law, and that this law, if it worked without friction, would give to every agent of production the amount of wealth which that agent creates”.

Seen in this light, wealth accumulation is a positive sum game – higher levels of wealth reflect superior productive capacity, and people generally get what they deserve. There is some truth to this, but it is only a very small part of the picture. When it comes to how wealth is created and distributed, many other forces are at work.

Wealth, property and plunder

The measure of wealth used by the OECD is ‘mean net wealth per household’. This is the value of all of the assets in a country, minus all debts. Assets can be physical, such as buildings and machinery, financial, such as shares and bonds, or intangible, such as intellectual property rights.

But something can only become an asset once it has become property – something that can be alienated, priced, bought and sold. What is considered as property has varied across different jurisdictions and time periods, and is intimately bound up with the evolution of power and class relations.

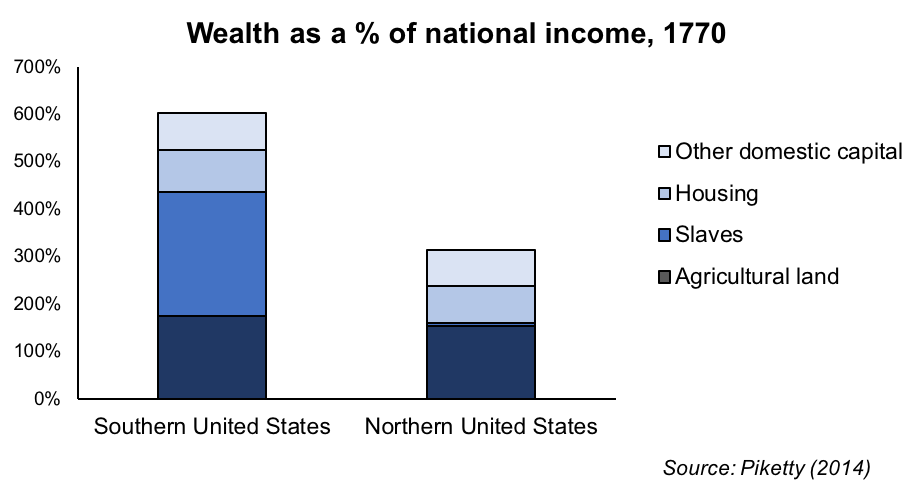

For example, in 1770 wealth in the southern United States amounted to 600% of national income – more than double the equivalent figure in the northern United States. This stark difference in wealth can summed up by one word: slavery.

For white slave owners in the South, black slaves were physical property – commodities to be owned and traded. And just like any other type of asset, slaves had a market price. As the below chart shows, the appalling scale of slavery meant that enslaved people were the largest source of private wealth in the southern United States in 1770.

When the United States finally abolished slavery in 1865, people who had formerly been slaves ceased to be counted as private property. As a result, slaveowners lost what had previously been their prized possessions, and overnight over half of the wealth in the southern US essentially vanished. All of a sudden, the southern states were no longer “wealthier” than their northern neighbours.

But did the southern states really become any less wealthy in any meaningful sense? Obviously not – the amount of labour, capital and natural resources remained the same. What changed was the rights of certain individuals to exercise an exclusive claim over these resources.

But the wealth that had been generated by slave labour did not disappear, and it wasn’t only the USA that benefitted from this. Many of Britain’s major cities and ports were built with money that originated in the slave trade. Several major banks, including Barclays and HSBC, can trace their origins to the financing of the slave trade, or the plundering of other countries’ resources. Many of Britain’s great properties, which today make up a significant proportion of household wealth, were built on the back of slave wealth. Even today, many millionaires (including many politicians) can trace some of their wealth to the slave trade.

The lesson here is that aggregate wealth is not simply a reflection of the process of accumulation, as theory tends to imply. It is also a reflection of the boundaries of what can and cannot be alienated, priced, bought and sold, and the power dynamics that underpin them. This is not just a historical matter.

Today some goods and services are provided by private firms on a commodified basis, whereas others are provided socially as a collective good. This can often vary significantly between countries. Where a service is provided by private firms (for example, healthcare in the USA), shareholder claims over profits are reflected in the firm’s value – and these claims can be bought and sold, for example on the stock market. These claims are also recorded as financial wealth in the national accounts.

However, where a service is provided socially as a collective good (such as the NHS in the UK), there are no claims over profits to be owned and traded among investors. Instead, the claims over these sectors are socialised. Profits are foregone in favour of free, universal access. Because these benefits are non-monetary and accrue to everyone, they are not reflected in any asset prices and are not recorded as “wealth” in the national accounts.

A similar effect is observed with pension provision: while private pensions (funded through capital markets) are included as a component of financial wealth in the OECD’s figures, public pensions (funded from general taxation) are excluded. As a result, a country that provides generous universal public pensions will look less wealthy than a country that rely solely on private pensions, all else being equal. The way that we measure national wealth is therefore skewed towards commodification and privatisation, and against socialisation and universal provision.

Capital gains, labour losses

The amount of wealth does not just depend on the number of assets that are accumulated – it also depends on the value of these assets. The value of assets can go up and down over time, otherwise known as capital gains and losses. The price of an asset such as a share in a company or a physical property reflects the discounted value of the expected future returns. If the expected future return on an asset is high, then it will trade at a higher price today. If the expected future return on an asset falls for whatever reason, then its price will also fall.

Marginal productivity theory states that each factor of production will be rewarded in line with its true contribution to production. But although presented as an objective theory of distribution, marginal productivity theory has a strong normative element. It says nothing about the rules and laws that govern the ownership and use of the factors of production, which are essentially political variables. For example, rules that favour capitalists and landlords over workers and tenants, such as repressive trade union legislation and weak tenants’ rights, increase returns on capital and land. All else being equal, this will translate into higher stock and property prices, which will increased measured wealth. In contrast, rules that favour workers and tenants, such as minimum wage laws and rent controls, reduce returns on capital and land. This in turn will translate into lower stock and property prices, and lower paper wealth.

Importantly, in both scenarios the productive capacity of the economy is unchanged. The fact that wealth would be higher in the former case, and lower in the latter case, is a result of an asymmetry between how the claims of capitalists and landlords are recorded, and how the claims of workers and tenants are recorded. While future returns to capital and land get capitalised into stock and property prices, future returns to labour – wages – do not get capitalised into asset prices. This is because unlike physical and financial assets, people do not have an “asset price”. They cannot become property. As a result, it is possible for measured wealth to increase simply because the balance of power shifts in favour of capitalists and landowners, allowing them to claim a larger slice of the pie at the expense of workers and tenants.

To the early classical economists, this kind of wealth – attained by simply extracting value created by others – was deemed to be unearned, and referred to it as ‘economic rent’. However, ever since neoclassical economics replaced classical economics as the dominant school of thinking in the late 19th century, economic rent has been increasingly marginalised from economic discourse. To the extent that it is acknowledged, it is usually viewed as being peripheral to the story of wealth accumulation, resulting from ‘market frictions’, such as monopsony and asymmetric information, which give rise to certain instances of ‘market power’. For the most part, economists have tended to focus on the acts of saving and investment which drive the real production process. But on closer inspection, it is clear that economic rent is far from peripheral. Indeed, in many countries it has been the main story of changing wealth patterns.

To see why, let’s return to the OECD wealth statistics. Recall that net wealth per household in Britain is more than double what it is in Germany, even though Germany is far more productive than the UK. This can partly be explained by comparing the power dynamics associated with each factor of production.

Let’s start with land: Germany has among the strongest tenant protection laws in Europe, and many German cities also impose rent controls. This, along with a banking sector that favours real economy lending over property lending, means that Germany has not experienced the rampant house price inflation that the UK has. Remarkably, the house price-to-income ratio is lower in Germany today than it was in 1995, while in the UK it has nearly tripled over the same time period. The fact that houses are not lucrative financial assets, and renting is more secure and affordable, means that the majority of people choose to rent rather than own a home in Germany – and therefore do not own any property wealth.

In Britain, the story couldn’t be more different. Over the past five decades Britain has become a property owners’ paradise, as successive governments have sought to encourage people onto the property ladder. Taxes on land and property have been removed, and subsidies for homeownership introduced. The deregulation of the mortgage credit market in the 1980s meant that banks quickly became hooked on mortgage lending – unleashing a flood of new credit into the housing market. Rent controls were abolished, and the private rental market was deregulated. Today tenant protection is weaker than almost anywhere else in Europe. Meanwhile, the London property market has served as a laundromat for the world’s dirty money. As Donald Toon, head of the National Crime Agency, has described: “Prices are being artificially driven up by overseas criminals who want to sequester their assets here in the UK”.

The result has been an unprecedented house price boom. Since 1995, skyrocketing house prices have increased value of Britain’s housing stock by over £5 trillion – accounting for three quarters of all household wealth accumulated over the same period. While this has been great news for property owners, it has been disastrous for tenants. As I’ve written elsewhere, the driving force behind rising house prices has been rapidly escalating land prices, and we have known since the days of Adam Smith and David Ricardo that land is not a source of wealth, but of economic rent. The trillions of pounds of wealth amassed through the British housing market has mostly been gained at the expense of current and future generations who don’t own property, who will see more of their incomes eaten up by higher rents and larger mortgage payments.

So while German property owners have not benefited from skyrocketing house prices in the way that they have in Britain, the flipside is that German renters only spend 25% of their incomes on rent on average, while British renters spend 40%. The former is captured in the OECD’s measure of wealth, while the discounted value of the latter is not.

Now let’s look at capital. In the UK and the US, the goal of the firm has traditionally been to maximise shareholder value. In Germany however, firms are generally expected to have regard for a wider range of stakeholders, including workers. This has led to a different culture of corporate governance, and different power dynamics between capital and labour.

Large companies in Germany must have worker representatives of boards (referred to as ‘codetermination’), and they are also required to allow ‘works councils’ to represent workers in day-to-day disputes over pay and conditions. The evidence indicates that this system has led to higher wages, less short-termism, greater productivity, even higher levels of income equality. The quid pro quo is that it also tends to result in lower capital returns for shareholders, as workers are able to claim more of the surplus. This in turn means that German firms tend to be valued less than their British counterparts on the stock market, which contributes to lower levels of financial wealth.

None of this means that Germany is poorer than Britain. Instead, it just reflects the fact that German capitalists and landowners have less bargaining power than they do in the UK, while workers and tenants have more power. While lower shareholder returns and house prices are reflected in the OECD’s measure of wealth, better pay and conditions and lower rents are not.

Conclusion

All statistics tell a story, but stories can be told from different perspectives. Embedded in the definitions of all economic statistics are value judgements about what is desirable and what is undesirable, which in turn shape the way we think about the economy. At the moment, the way we measure the wealth of nations mainly reflects the fortunes of capitalists and landowners rather than workers and tenants. Britain looks wealthier than Germany on paper, but this does not reflect the lived reality for most people. While it’s important not to overstate the extent to which statistics can influence the real world, this is important for at least three reasons.

Firstly, it illustrates how seemingly objective metrics often have ideological assumptions baked into them. While there is already a well-established literature on alternatives to GDP, many economic metrics are used in economic analysis and policy appraisal without any critical appraisal of their underlying ideological assumptions. This needs to change.

Second, it highlights how paper wealth has in many places become decoupled from productive capacity, and how conflating the two can be highly misleading. This is particularly the case where zero sum rentier activity is widespread, as in the case of Britain. Such discrepancies raise the question of whether the way that we currently measure wealth is really the most sensible.

But most importantly, it illustrates that the distribution of wealth has little to do with contribution or productivity, and everything to do with politics and power. As J.W. Mason states: “It’s bargaining power, it’s politics, all the way down.”

For economists who see their discipline as a ‘value free’ science which is separate from politics, this is uncomfortable territory. But if the aim is to understand the economy as it really exists, then analysing power beyond the narrow concept of ‘market power’ is essential. Among other things, this means grappling with the power dynamics that underpin ownership and property relations, as well as those that that drive inequalities between different social groups and identities.

It’s been 200 years since David Ricardo described the “principal problem” of political economy. Perhaps it’s time to revisit it.