The 51st State of Housing: The American housing crisis, and what it means for the UK

The ‘First Houses’: The first public housing in the US situated in New York City’s Lower East Side.

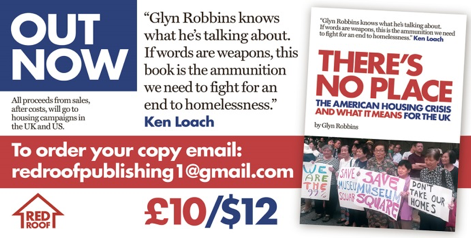

The following is an extract from the introduction to my book, ‘There’s No Place: The American housing crisis and what it means for the UK’. The book was published on 16th June 2017, two days after the Grenfell Tower fire. Three months later, it’s difficult to overstate the impact of the disaster. The deaths of at least 80 people (almost certainly more) have exposed not just the historic failures of housing policy, but also deeper fissures in our urban social fabric. Grenfell symbolises the conflict between housing as a private commodity, or a social asset – a dichotomy personified by Donald Trump. Before Grenfell, I argued the UK was following in the housing footsteps of the US, with potentially disastrous consequences. After Grenfell, that warning feels even more pertinent.

I’ve worked in and campaigned on housing in the UK for many years. During that time, I’ve become increasingly conscious of the threads linking – and ultimately binding – the development of trans-Atlantic housing policy. This cross-fertilisation has, at times, appeared to define the differences between the two nations, with attitudes to housing reflecting wider cultural and political divergence. But it has now reached a critical point of convergence reflected in a common housing crisis. In both countries, plans are well advanced to detach housing, once and for all, from any semblance of public or non-profit provision and in the words of a right-wing UK housing academic, privatise the social rented stock and “allow market relations to develop”.

I argue there are five broad features of this shared US-UK housing experience:

- Relentless government attacks on municipally-owned rented housing as part of a wider assault on public services.

- The unchecked rise of private landlordism as part of a broader advancement of private sector, profit-seeking interests.

- Growing corporate links between US and UK housing in the context of global speculative property investment.

- Socially-divided cities characterised by displacement and denigration of poor and working class people and communities.

- The ideological promotion of housing as a commodity, not a home.

The common origins of US and UK housing policy lie in attempts to alleviate the conditions of the 19th century industrial city. When utopian, charitable and philanthropic measures proved inadequate, the American and British establishments, under mounting pressure from organised labour, reluctantly accepted the need for action. However, from this early stage, differences emerged. In 1890, the Housing of the Working Classes Act enabled newly-created UK public authorities to clear and rebuild slums, paving the way for council housing. In 1891, the London County Council began demolishing the notorious Nichol rookery in Bethnal Green, east London. Nine years later the Prince of Wales opened the thousand-home Boundary Estate, the first of its type and scale in the world, still standing as a testament to its enduring quality and still in public ownership.

Faced with the same problem, the 1901 New York Tenement House Act concluded that improving the conduct of private developers and landlords, rather than replacing them, was the route to better conditions. As Peter Hall notes, American reformers feared that:

…public housing would mean a ponderous bureaucracy, political patronage (and) the discouragement of private capital…in comparison with Europe, it was to set the cause of public housing back for decades.

From this fork in the road, both nations proceeded in a fashion reflecting their social characteristics. In the first quarter of the 20th century, the UK continued to build council housing against the backdrop of a strengthening labour movement and periodic rent strikes which gave added impetus to creating alternatives to private landlordism. There were similar tenants’ mobilisations in the US. But the country’s labour movement struggled to recover from a vicious establishment attack in the aftermath of the Russian revolution. It was not until the crisis of the Great Depression that the US began to explore the possibilities of large-scale State intervention on housing.

From the outset, US public housing was treated as ancillary to various other policy objectives, particularly job creation, but never as a rival to the supremacy of home ownership, which has enjoyed continuous financial, political and ideological support from US governments. The same is true of the UK, but for most of the 20th century, council housing was also part of the social and policy mainstream, providing a home to 30 per cent of the UK population by the end of the 1970s.

When the 1937 US Housing Act was introduced, it could only gain political endorsement on the basis that it would not impose Federal decree over local decision making, a tension that continues to shape US housing policy. From the beginning, there was also an absolute requirement that public housing would never be allowed to rival the private sector as the primary provider of new homes. There is something constant and fundamental in the relationship between America and property that needs to be recognised. The founding acts and principles of the nation were based on acquisition and enshrinement of land rights. These were exercised, most obviously and brutally, at the expense of Native Americans and established a commodification of land that has been ingrained in the European American psyche.

But it would be wrong to regard US housing policy as monolithic. Since the 1930s there have been several changes in emphasis which, while not approaching the UK’s post-war political consensus in favour of building council homes, demonstrate a recognition that government intervention is needed in the housing market.

The expansion of US municipal housing quickly gave way to the extension of government mortgage subsidies which became a far more embedded feature of the country’s housing policy. Initially made available to former servicemen, the scale of State support for private home ownership soon outstripped that for public housing. This spurred the development of the American suburbs and entrenched ethnic and skin colour divisions in US cities. Only white veterans were entitled to government-funded low-cost home ownership. African-Americans were effectively excluded from the expanding suburbs and consigned to neglected inner-city areas, often with appalling housing conditions. Housing has been an instrument of racism in many times and places, but has gained prolonged legitimacy in America.

Accumulating anxiety about America’s urban crisis, periodically heightened by street unrest and rebellions, has directly influenced housing policy. Concerns, often expressed in moralistic, stigmatising and racialised terms, have been visited on public housing in particular. Since the 1960s disinvestment and denigration has led to the sector being widely viewed as “the housing of last resort”. A series of stereotypes have politically, physically and socially marginalised public housing and the people who live in it.

UK council housing has been the target of similar treatment since the 1980s. In both countries, the winding-down of direct State housing investment and provision has been accompanied by a variety of devices for advancing the role of the private sector, with significant trans-Atlantic mimicry. Both US and UK governments have used the camouflage of so-called partnership and regeneration to achieve the privatisation of public and council housing respectively. This ideologically-driven assault has sought to create a more diverse range of housing providers and funding mechanisms, leading to increasingly complex and misleading definitions of affordable and social housing.

While this book will focus on the growing resemblance between US and UK housing, there remain some fundamental differences. Perhaps the biggest of these is the extent of legal entitlements to housing. In the UK, certain categories of people – notably parents with children – can still present themselves as homeless to a local authority which then has a duty to house them (however inadequately). No such protection exists in the US. Although housing rights in the UK, particularly for the homeless, have been substantially reduced, the most vulnerable still have a safety net that doesn’t exist across the Atlantic. Furthermore, a substantial part of access to low cost housing in the US is controlled and administered by a voucher system which enables eligible tenants to find housing in the public, or more likely, private rented sector. UK Housing Benefit (HB) is increasingly acting like a voucher system, but is part of a wider system of welfare benefits which doesn’t exist in the US. Similarly, although council and housing association housing sit within the wider context of the UK welfare state, they have never been considered “welfare housing” as their US equivalents often are. Access to public and other non-market housing in the US is rigorously controlled by means-testing, with rigid income limits and rent calculated as a proportion of income. Until the advent of the Housing and Planning Act in 2016, this was not the case in the UK.

Historically, the private rented sector has been far more sizeable in the US. This has changed dramatically in recent years. Private renting fell steadily in the UK during most of the 20th century – in inverse proportion to the rise of council housing – and settled at around eight per cent. That trend has now reversed. UK private renting has doubled in the last decade and is fast approaching US levels of 30 per cent, while social housing has fallen to 16 per cent, of which council homes make up only half.

This book will describe and explore a host of local issues illustrating that US and UK housing are morphing. The transnational force driving them together is the increasing economic reliance of both countries on the so-called FIRE sector of finance, insurance and real estate (or property). This in turn relates to structural economic changes over the last four decades through the deregulation of global investment markets. The result is the increasing commodification of housing, now a speculative investment vehicle for vast flows of global capital, the volatility of which brought repossession and homelessness for many in the sub-prime crisis of 2007-8. The grip of the international property machine has intensified since the great recession. Its primary targets are the high value areas of US and UK cities where over-heated housing markets are transforming, traumatising and trashing local neighbourhoods, particularly those with high concentrations of non-market housing.

The cross-fertilisation of US-UK housing was graphically demonstrated in October 2015 at a London convention of global property developers. The three-day MIPIM-UK event billed itself as a “gathering of professionals looking to close deals in the UK property market”. Sixteen US-based companies were represented at MIPIM-UK and among the subjects for discussion was The American Way. The US template of large-scale institutional investment in private renting was fawned over and illustrated in the conference brochure by a picture of the road to a house paved with dollar bills.