Not in it together: the distributional impact of austerity

Image: “Follow Your Dreams/Cancelled”, Banksy/Chris Devers, Creative Commons License.

During his time as Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne liked to say “we are all in this together”. But until now it has been difficult to assess the distributional effects of the tax and welfare policies of the 2010-15 coalition government and the current Conservative government. The government has refused to do the calculations, for obvious reasons.

But in November the Equalities and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) published a distributional assessment of the impact of tax and welfare reforms between 2010 and 2017, modelled in 2021/22 tax year. It did not receive much attention, and does not include any discussion or set of recommendations. But the analysis in the paper is damning. It highlights just how regressive the tax and welfare changes have been, with the greatest burden falling on the poorest, ethnic minorities, women, children and the disabled.

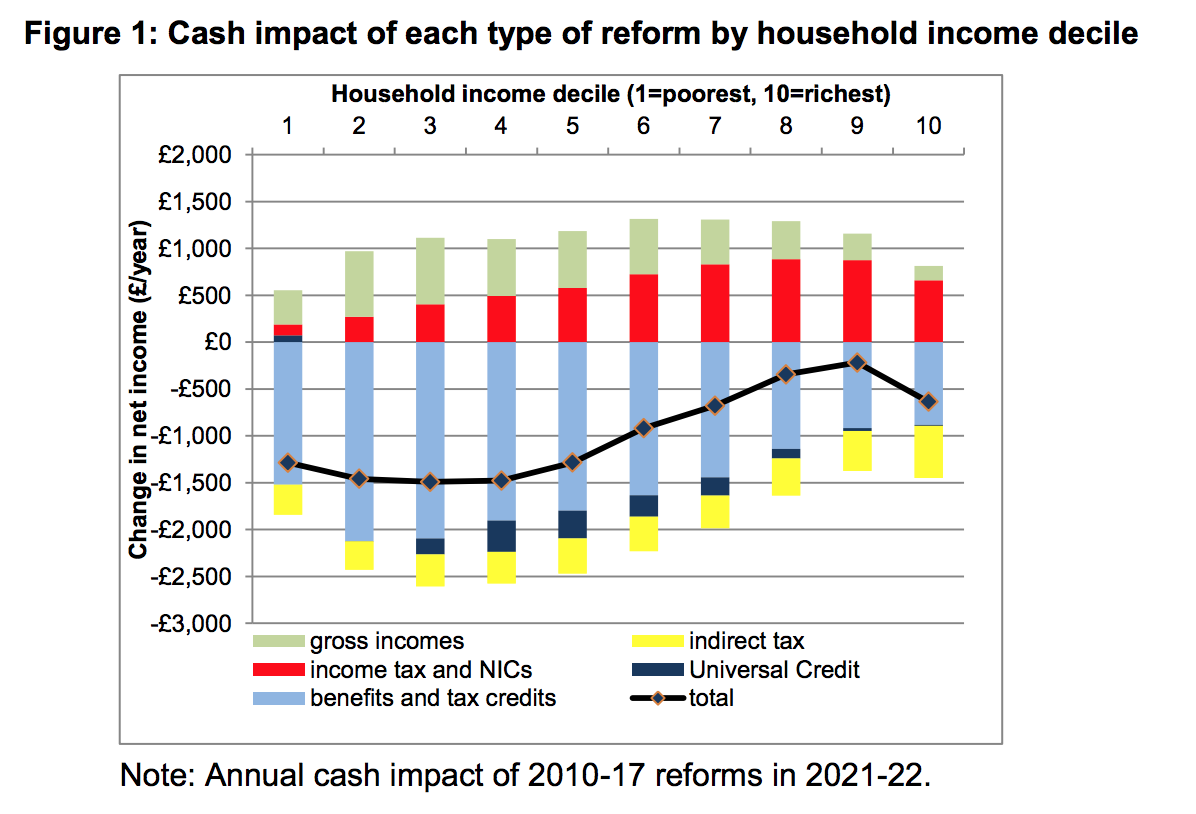

The researchers modelled the effects of changes in taxes and benefits – specifically income taxes, national insurance contributions, VAT and excises, benefits and social security transfers, tax credits and the national minimum wage/living wage. These are then analysed in terms of household income distribution by decile, from the poorest to the richest. The results are initially expressed in terms of effects on cash flows for each decile:

Average net cash losses are greatest for the bottom 40% of households, at around £1,500 per year. This compares to just £200 for households in the second top decile. The largest losses are due to changes in benefits and tax credits, which amount to more than £2,000 per household for the lower deciles.

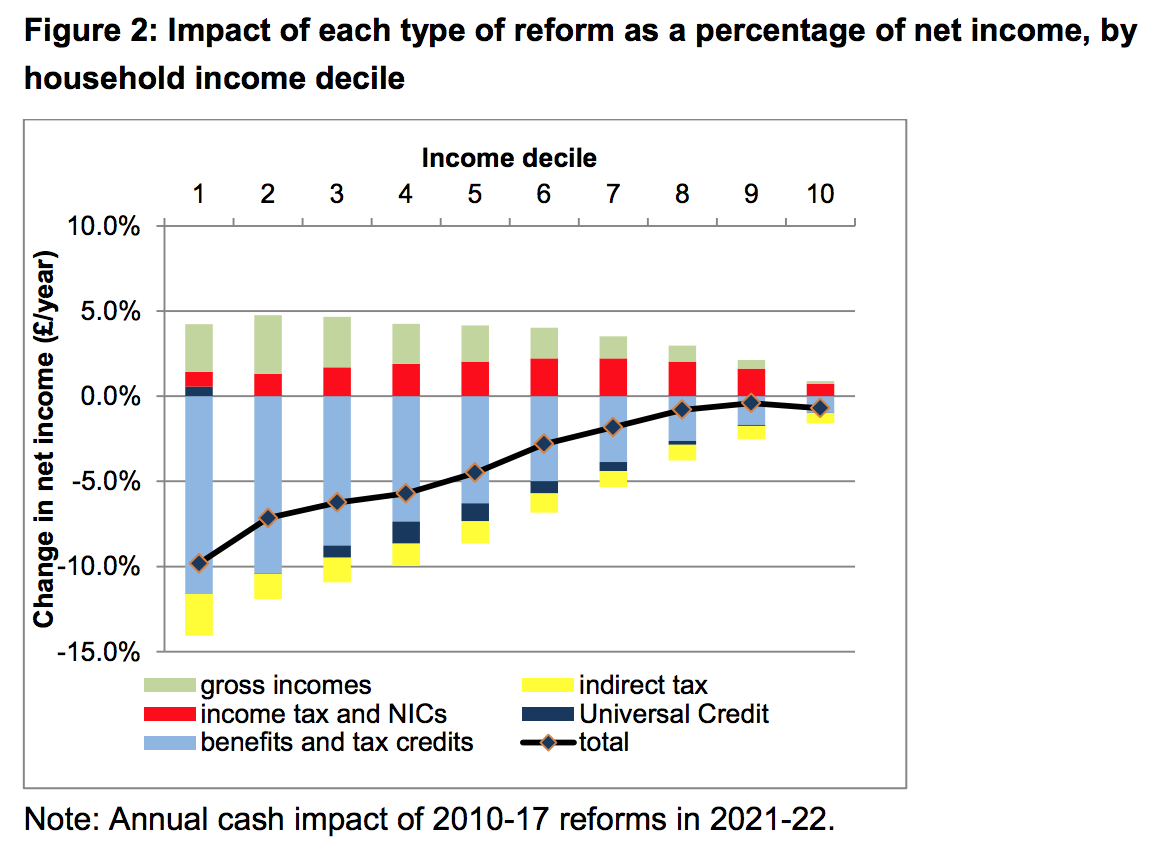

These cash estimates are then converted into shares of net household income. The results are shown to be highly regressive, with the poorest suffering the greatest proportional loss:

Households in the lowest decile have seen net incomes fall by 10%. In contrast, households in the second top decile have only seen net incomes fall by 0.4%.

The report then looks at the impact of the tax and benefit changes on households with different characteristics. Here the results are even more striking.

Ethnic minority households have suffered more than white households, with the average loss for African, Caribbean and Black British households amounting to 5% of net income – more than double the equivalent loss for white households.

Households with one or more disabled member have seen net incomes fall by £2,500 a year. For households with a disabled child, losses amount to more than £5,500 a year on average. This compares with a reduction of about £1,000 a year for households without any disabled members.

Lone parents have seen net incomes fall by 15% of net income on average, compared to between 0% to 8% for other family groups. Women have been effected more than men at every income level, with losses averaging £940 compared with £460 for men.

By age group, the biggest average losses are for those aged 65-74 who have seen net incomes fall by £1,450 per year, primarily due to the increase in the pension age to 66 in 2021 as a result of the Pensions Act of 2011. Those in the age range 35-44 are losing £1,250 per year on average.

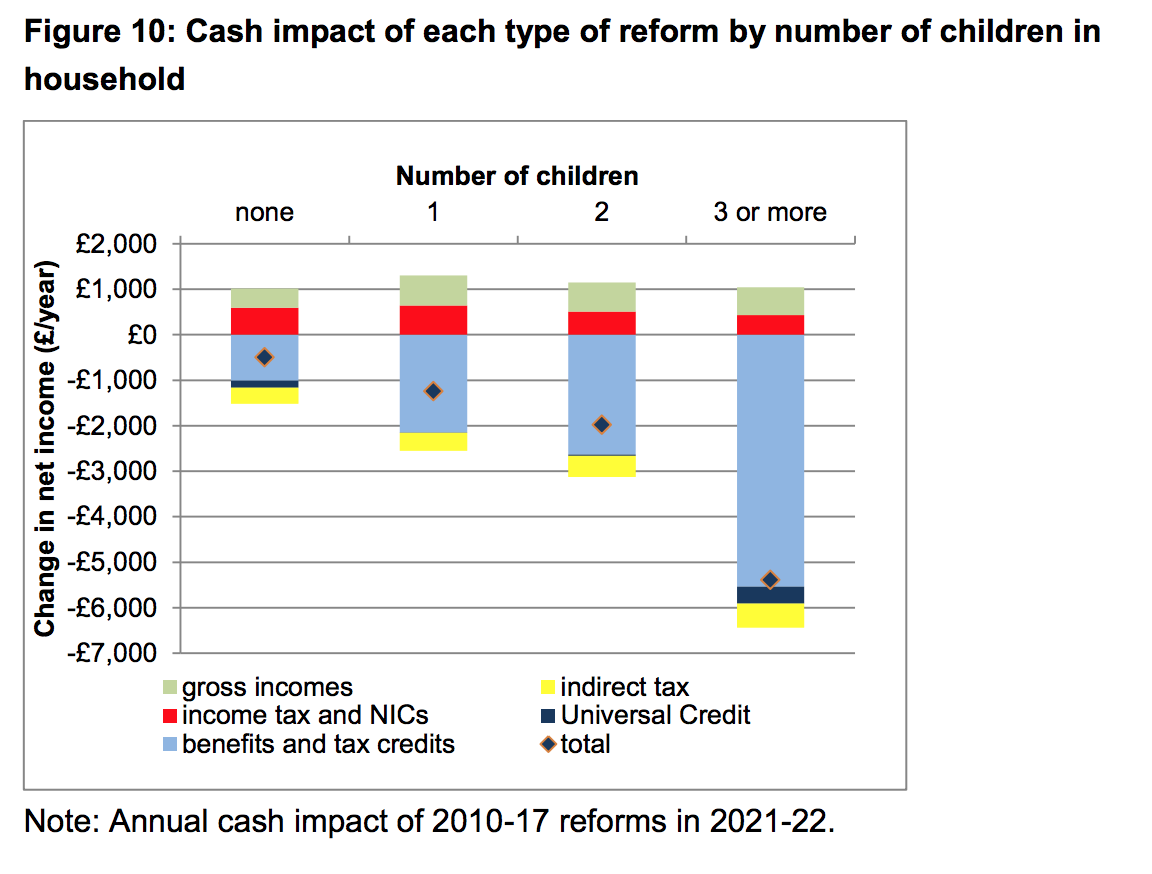

Households with three or more children have been particularly hard hit, with cash losses amounting to £5,400 per year. In contrast, losses for households with no children have only amounted to £500 a year.

There are currently four million children living in poverty – 30% of all children in 2015/16. Between 1998-2011 public policy took 800,000 children out of poverty, but this achievement has been reversed by governments since 2010. Some two-thirds of children living in poverty live in families where at least one person is working. 36% of all children in poverty live in families where there are three or more children, so size of family is a significant determinant of child deprivation.

There are currently four million children living in poverty – 30% of all children in 2015/16. Between 1998-2011 public policy took 800,000 children out of poverty, but this achievement has been reversed by governments since 2010. Some two-thirds of children living in poverty live in families where at least one person is working. 36% of all children in poverty live in families where there are three or more children, so size of family is a significant determinant of child deprivation.

It is hard to believe that a government would target its cuts on children, and especially children in large families. Inevitably the government’s policies will add to the numbers of children living in poverty, and have major consequences for the lives that children lead.

How is it possible to pursue tax and expenditure policies that have such a skewed set of outcomes? One might like to think it is simply incompetence. But despite the impact of the changes now being clear, the government has continued down the same track – irrespective of the effects on the living standards of the poorest in our society.

There have been also huge cuts in local authority funding affecting services for children, the disabled, the elderly, and targeted services such as Sure Start centres. Funding has also been cut for breakfast clubs in schools, sports and recreation facilities, libraries and education.

All of these policies cumulatively add to the pressures on those households least able to manage. At the same time, investment in social housing has more or less ceased, while taxes on corporations and the rich have been reduced.

The Government can and should be held to account for their policies. Going forward, Parliament should require a full distributional analysis to be produced for all tax and expenditure changes at the time of a Budget. The government should also have to demonstrate that all proposed changes are consistent with existing human rights and other equalities legislation. The tax and welfare changes since 2010 clearly contravene rights and obligations in areas such as child poverty and the rights of children, ethnicity and gender, and trample on the rights of the disabled.

The strategy of hammering the poorest in society in pursuit of some chimera of a reduced level of national debt has failed. Surely, we have had enough. It is time to use fiscal policy in the interests of everyone.