How deliberative democracy can rebuild trust in our economic institutions

Britain has never had especially high levels of trust in economic and political institutions. But in recent years, levels of trust have fallen to a point that raises questions over the legitimacy of those institutions. At the RSA, the motivation for our Citizens’ Economic Council work was a view that the quality of economic debate in the UK was poor and deteriorating.

Our new report ‘Building a Public Culture of Economics’ makes the case for rebuilding trust in, and the trustworthiness of, political and economic institutions. We make several recommendations to strengthen the democratic management of our economy.

Democratic voice

Democracy is a structure designed to find solutions that work for the largest possible section of the population – for the public good. Democracy is about listening and compromise, not individual interests winning because they have the loudest voice.

The divisions in British society brought to light by the EU referendum, and indeed demonstrated across the world by the rise of populist politics in the US and much of Europe, are a threat to democracy. They threaten democracy not because people want different things to what the infamous “experts” – our economists and politicians – tell us we should want, but because they are creating “weaponised narratives“ of us and them. Narratives which shout loudly into the void, uncaring of other voices and unwilling to listen or compromise, polarising society to the point where we can’t agree how to govern our economy anymore.

To make matters worse, many media organisations appear to be struggling to report the news in a balanced way that gives appropriate respect to the reality of people’s lived experiences around the country. This can be considered true of traditional media organisations and new social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube. As research from City University London shows that 95% of journalists in the UK are white, 55% are men and 36% live in London. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that news reporting has a diversity problem.

Our report evidences a widening chasm not just between expert and citizen, but also between citizen and citizen. These diverging views in and of themselves are not problematic, but we argue that it is the failure of these perspectives to engage critically and respectfully with each other that is undermining the quality of public discourse on the economy.

So what should we do about it?

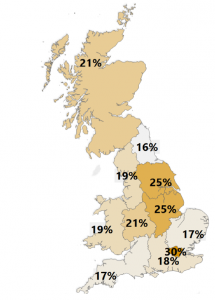

Despite the EU referendum, a Populus poll commissioned by the RSA reported that only 21% of respondents felt they had either a lot or a little influence on the Government handling of Brexit as Britain initiated the process of leaving the EU. This figure was significantly higher in London, and lower in areas that will arguably be most affected by Brexit such as the north-east and Wales (as shown in the map below).

This demonstrates how trying to distil an issue as huge and complex as whether or not to leave the EU into a binary black and white vote will not answer the concerns of a public, who have complex needs, experiences, fears, and hopes. Instead, we need a democratic mechanism that allows for a nuanced discussion of the different stakeholders and trade-offs within such a decision. We need to ‘build a public culture of economics’ in which diverse citizen voices can be included in and have influence over economic decision-making so that outcomes are reflective of the needs of people across the country. We argue that the process of deliberation, where citizens exchange arguments and consider different claims designed to secure the public good, could be a way to start these necessary and meaningful conversations, adding to democratic structures that already exist and strengthening the democratic management of our economy.

Deliberative democracy

Deliberation emphasises collaboration, cohesion and empathy in political discourse. It also greatly enhances the sense of agency of participants and, we contend, it could also increase the sense of agency and degree of trust and confidence among the wider public if the use of deliberative democracy were to become widespread, consistent and well publicised.

This is not to say that everything is perfect in the realm of deliberative democracy: it is impossible to represent all 65 million people living in the UK within a deliberative process, for example. What it can do however is bring together a greater diversity of voices than currently exist in the media or in our representative form of democracy, and use their different perspectives to explore and widen the debate on how and why we make economic decisions. Just as the British public trust our criminal jury system despite not having necessarily served on one, our opinion survey revealed that 47% of people would trust economic policymaking more if they knew that ordinary citizens had been formally involved in the process.

Deliberation strengthens representative democracy by shortening the feedback loops between decision-makers and those governed. It also strengthens direct democracy by ensuring that, before individuals cast a direct vote on an issue, they have directly participated in, or at least observed, a vibrant and respectful democratic discourse.

Where next?

We argue that conversations about the economy start at home. To build a strong democratic discourse about economics, it is essential to meet people where they are and to proceed from people’s everyday experience of the economy through work at play and in their communities. This suggests that the most fruitful domain for applying deliberative democracy may be, at least initially, at the local and regional level.

At our report launch last week, Bank of England Chief Economist Andy Haldane announced that the Bank of England wanted to “climb the ladder of engagement”, moving up from the rungs of ‘inform’ towards ‘collaborate’, and would be acting upon our recommendation for the Bank to pilot Citizen’ Reference Panels with each of its 12 Regional Agents.

Our other recommendations are addressed to HM Treasury, national and local government, and combined authorities in the context of devolution. Will they show similar leadership and understanding in the need to diversify the voices within our democracy?

Read ‘Building a Public Culture of Economics’ to find out more.