How we can win the Nordic model for the UK: an interview with George Lakey

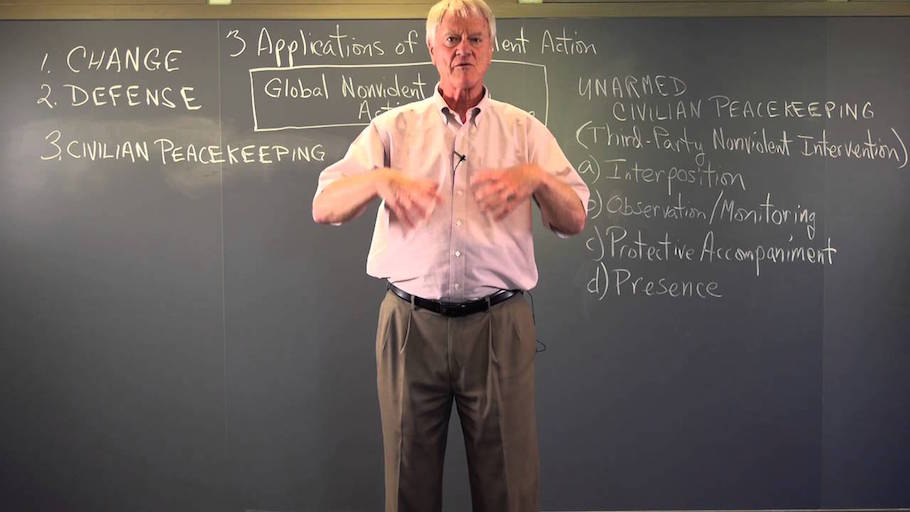

George Lakey. Image: YouTube, fair use.

Ian Sinclair interviews George Lakey about the popular uprisings which led the Nordic economies to be the most successful on earth.

Active in social movements since the 1960s, in 1971 American George Lakey co-founded the radical group Movement for a New Society, and in 1973 he wrote the influential book Strategy for a Living Revolution, a guide for achieving nonviolent revolution. More recently he was Visiting Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at Swarthmore College in the United States and has been involved in the Earth Quaker Action Team campaign opposing mountain-top removal coal mining.

Now 79-years old, Lakey has just published Viking Economics: How The Scandinavians Got It Right – And How We Can, Too. Having married a Norwegian, lived in Norway for a year in 1959 and visited the region many times since, he argues the superior Nordic model is within reach of the neoliberal US and UK, although it will take large-scale struggle with the economic elite to achieve it.

I interviewed him about ‘the Nordics’, their history and how their social and economic policies could be won in the US and UK.

Ian Sinclair: What have the Nordic countries “got right”?

George Lakey: What economists call the Nordic economic model generates an extraordinary amount of both equality and individual freedom. We can see the synergy on both small and large levels in those countries.

All new parents, for example, are offered many months of paid family leave when they give birth or adopt. In a mixed-gender couple, part of the leave is reserved for the male. If he refuses to take his part of the leave, the couple loses his part of it. With parental paid leave each member of a couple experiences fuller opportunity to parent in the first year of a child’s life – or not, as that person chooses. In other societies that opportunity would be reserved for the better off. At the same time, the policy nudges the couple toward equality in roles and responsibilities.

This is one of a thousand features supporting both equality and freedom made possible by the Nordic design. A macro example is a typical large Norwegian corporation being owned largely by government but individuals invited to own shares as well up to a certain amount. Widespread public ownership, alongside the large cooperative sector, reduces the inequality that otherwise accompanies an economic market. Substantial individual wealth and inheritance taxes further reduce inequality. Nevertheless, the entrepreneurial spirit is alive and well, and there are more start-ups in Norway per capita than in the US. Entrepreneurship can be seen as the application of creativity, and it gets public support just as does the thriving sector of performing arts.

While the countries I studied – Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden – may share an economic design with a half century track record of remarkable outcomes, they are not utopias. Norwegians admit to me, “We are a nation of complainers.” I’ve met many Nordics who see more problems that need to be solved.

IS: In your book you note that at the turn of the twentieth century the Nordic countries had very high levels of inequality and poverty, with many people emigrating to the United States and elsewhere. However, as you say, today the Nordic countries consistently top international measures for human development and well-being. How did this transformation occur?

GL: People organized themselves into mass direct action movements to force the economic elite out of dominance. Of course the privileged defended themselves, suppressing the press, jailing organizers, hiring strikebreakers. The historic details vary for each country. In each case it required cross-class alliances.

In Norway the elite organized the Patriotic League in 1926 to wade into strikes and violently defend replacement workers. In the ‘30s [the government minister Vidkun] Quisling organized a Norwegian Nazi paramilitary force to march in the streets to provoke violent clashes with working class activists. Nonetheless, the nonviolent militancy in the workplace and rural areas made the country ungovernable, and the economic elite was forced to allow the workers’ and farmers’ movements to take leadership of the country.

For Sweden the turning point came in 1931 when, in Ådalen Valley, workers struck three lumber mills at once and four thousand workers picketed the owners and government officials. Troops fired into the workers’ march, killing five and injuring five more. The workers called a national general strike, forcing the conservative government out of power and replacing it with the Social Democrats who ruled almost without a break until 1976.

IS: You also discuss the key role played by trade unions in this transformation.

GL: To make a nonviolent power shift a mass of people whose cooperation is necessary to operate the system must be willing to force change by withholding that cooperation. A century ago, when nonviolent struggle appeared to have only a few tactics in its arsenal, the obvious means of noncooperation was the strike. Industrialization was generating the “nonviolent soldiers” who could do strikes: the workers. These days we know far more nonviolent tactics that can make a country ungovernable. Mass noncooperation can be precipitated in more ways than the Nordics did, so today’s revolutionary strategy is not so dependent on the workers and their unions.

Union organizations, of course, vary widely on their willingness to wage class struggle. The Nordics give us a recent example.

The influence of Thatcherism in the 1980s became threatening to Scandinavians and the unions there lost confidence. The governments of Norway and Sweden relaxed some bank regulations, with nearly disastrous results. Observing this trend among their Viking cousins and knowing Thatcherism was also growing in Denmark, the Danish workers defied their own unions and launched a general strike in 1986, including barricading parliament in its building in Copenhagen. The workers frustrated the neo-liberals’ plans and prevented Danish bankers from running wild. Remembering the distinction between the union leadership and the members can matter for strategy.

IS: What is the current political situation in Scandinavia today? Are the gains made by the social movements in the twentieth century holding firm or being degraded?

GL: Forcing a power shift in the last century doesn’t mean the class struggle disappeared. Small countries are vulnerable not only to internal tensions but also to manipulation by global market forces. Knowing this, Norway refused to join the EU, even before it gained the security of its oil find. Norwegians could see that the EU was led by neo-liberals, and they wanted the freedom to continue on their left course. Sweden and Denmark did join the EU but stayed out of the Eurozone, maintaining maneuvering room for themselves.

In my book I present a mixed picture of today’s Nordic class struggles: both losses and wins. Here are a few of the many on both sides. Inequality has risen, although they remain at the top of the heap for equality. Belts are tightening on services, although they are still far more generous than other countries. Sweden struggles with maintaining the Nordic full employment policy. The mighty cooperatives are not matched by achievements in worker democracy in the other workplaces.

On the other hand, Sweden took in per capita the most Middle Eastern refugees of any European nation. Norwegian citizens can challenge Norwegian corporations’ behavior in the Global South and force changes. Iceland only a few years ago jailed bankers and brought down their government in the “Pots and Pans Revolution.” All the Nordics are speeding ahead in addressing climate change.

The Nordics remain largely faithful to their trademark approach to benefits: not means-tested (“welfare”), but applied to all (universal). I don’t call those countries by the misleading term “welfare states.” They are actually “universal services states,” and that is key to their success in virtually abolishing absolute poverty.

IS: What strategies and tactics do you think activists in the US and UK should employ to move from our current neo-liberal, high inequality economies to something approximating the Nordic Model?

GL: First, we should learn from the example of the Danish 1986 general strike: “go on the offensive.” The Danish workers didn’t just try to defend previous gains – they fought for further gains for working people.

Gandhi and military generals agree on at least one point: nobody wins anything on the defensive! The activist history of the UK and US since the Thatcher/Reagan counter-revolution sadly forgot this strategic necessity of staying on the offensive – and paid the price. In fact, the biggest UK/US activist win since 1980 has arguably been rights for lesbian/gay/bisexual/trans people. The LGBT struggle stayed vigorously on the offensive!

Remaining on the offensive requires a vision of what we truly want. Vision is where our demands should come from rather than from our fear of what we might lose. The Scandinavians a century ago took the time to get out of their little activist groups to gain wide agreement on a positive vision.

This can put radicals in a dilemma. Many Nordic radicals who wanted to win understood that the movement’s vision couldn’t express the full extent of their personal yearnings and still gain broad agreement. The vision had to be seen as practical and achievable within the middle term, a horizon that could inspire all-out struggle.

A sufficient number of middle class intellectual radicals overcame their class training (to be superior, differentiating egos) so they could join the growing mass movement that could unseat the one per cent, thereby opening the space for all kinds of possibilities – even some radical ones.

We are in a fundamentally new political moment from that of the 1920s/30s. At that time, no one knew for sure if there was a variant of socialism that would actually work to achieve a high degree of equality, freedom and shared prosperity. Now, we know. There is a track record, an economy that consistently out-performs the Anglo-American economic model, despite the disadvantages of small countries in a fierce and globalized world. My book shows that the practical argument is now entirely on our side.

What remains strategically is to sharpen the art of nonviolent direct action campaigning that meets people where they are and deepens their skills and knowledge while building ever more powerful movements. It may be time to drop the one-off protest and routine march and rally! Campaigns with (a) specific grievances and (b) winnable demands and (c) a target that can be forced to grant the demand are the campaigns that empower. Empowered campaigners can then merge into mass movements that – when history opens the opportunity – become a “movement of movements” that can force a power shift.

The Nordic examples are included in an online, searchable database of over a thousand campaigns from nearly 200 countries: the Global Nonviolent Action Database. Campaigns range from those that have overthrown military dictatorships to those that forced local resolution of environmental dangers.

Campaigns are not sufficient to make a revolution, but their vitality, creativity, and escalating confrontation are central in making the power shift that gives us a chance to build the new society, as different from our present order as contemporary Scandinavia is different from that of a century ago.

IS: A common critique of your argument pushing for the US and UK to adopt Nordic-style economic and social policies is that it is unlikely to work as Nordic countries are very different to the US and UK – they are smaller, more homogenous and have very different political cultures. How do you respond to these challenges?

GL: The Nordic countries represent to me small laboratories in which experiments have been tried and conclusions reached. Through theory, trial and error they have achieved “best practices” in many areas, according to third party global measures.

Two attitudes are commonly held toward these practices. The first attitude was voiced by Hillary Clinton in an election debate with Bernie Sanders when he referenced a feature of Denmark’s political economy. “That’s Denmark,” Clinton said dismissively, certain it could have no relevance to the exceptionalist USA.

The second attitude was voiced by a delegation of Chinese economists and policy-makers who were sent by Beijing to investigate Norway. I interviewed researchers in Oslo who had previously received the Chinese. They told me they were surprised by the Chinese government’s interest. I was as well, knowing that China makes the U.S. seem a small and homogeneous country compared with its own size and cultural complexity.

When asked, the Chinese said some economic questions are affected by scale and cultural diversity, and some are not. The Chinese were curious to learn what had been working “in the lab,” eager to identify the features that could scale up to provincial or even national size within China.

As a curious sociologist, who is strongly dissatisfied with the US economy, it is easy for me to be interested in the best practices of others.

IS: Doesn’t the election of Donald Trump as president suggest, if anything, the American population is moving further away from supporting the things that make up the Nordic Model?

GL: The situation on the ground is the opposite from what you imagine. When we compare the votes for Trump and Clinton, we find that more supported Clinton than Trump, but the voters for the major candidates were far exceeded by those who didn’t vote for either Clinton or Trump – almost half the total electorate, most of whom didn’t bother to go to the polls at all.

The election reveals a deepening crisis of legitimacy for the American political class. In November the polls attracted the lowest percentage of eligible voters in 20 years – only 58%. Because of this, our next president was elected by roughly one in four of the eligible voters. And in exit polls, about one fifth of Trump’s voters said they don’t actually consider him to be competent to be president. To me, this does not sound like a mandate from the American people!

The story of voter participation is accompanied by the trend away from registering as Democrats or Republicans; more people are choosing “Independent.” Deep anger and alienation is felt by voters who feel abandoned by both of the major parties. Recent opinion polls asking about issues find majorities backing policies characteristic of the Nordic model, including aggressive anti-poverty measures, decreased rewards to the rich, the equality profile of Sweden rather than that of the US, and actively addressing the climate crisis.

For the history-minded, the combination of declining legitimacy of the established order with preference for an alternative is the recipe for system change.

The 1,000-year ago Viking spirit of expedition emerged in the twentieth century and inspired people to, economically-speaking, go where no one had gone before. We need not be so brave as the twentieth century Nordics were; we do not need to expedition. We can, more cautiously, learn from best practices already established, then take on the struggle with some confidence.