Winning the future – how we can end the advance of the right

Progressives need a plan built on what humans do best: creativity and care.

We need a plan. We need a story. We need to convince people of a better future. The left has utterly failed to tell a persuasive positive story about the future.

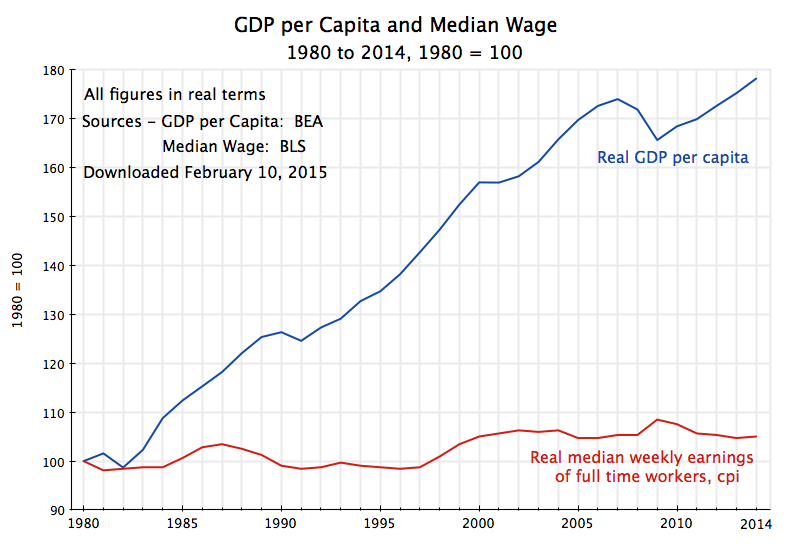

Since the late 1970s wages as a share of GDP have fallen. Meanwhile the earnings of the top 1% have raced ahead. Where people haven’t shared in the expected benefits of growth they have begun to ask serious questions about what the future holds for them.

We have allowed conservatives to present the only convincing alternative to this world as a return to a (largely imagined) past.

This is why immigration is the touchstone issue. While immigrants contribute more in taxes than they use in public services, and there is scant evidence of them reducing wages or ‘taking jobs’, they do offend the nostalgia for an imagined monocultural past.

And as with the worst medical misdiagnoses the reduction in immigration is likely to exacerbate all the problems its advocates believe it will solve. Losing valuable workers from our public services and the taxes they pay, and replacing them with retirees who will no doubt lose their access to Spanish health services will place a double strain on our NHS. If we don’t get our act together who knows which minority will be next to be scapegoated?

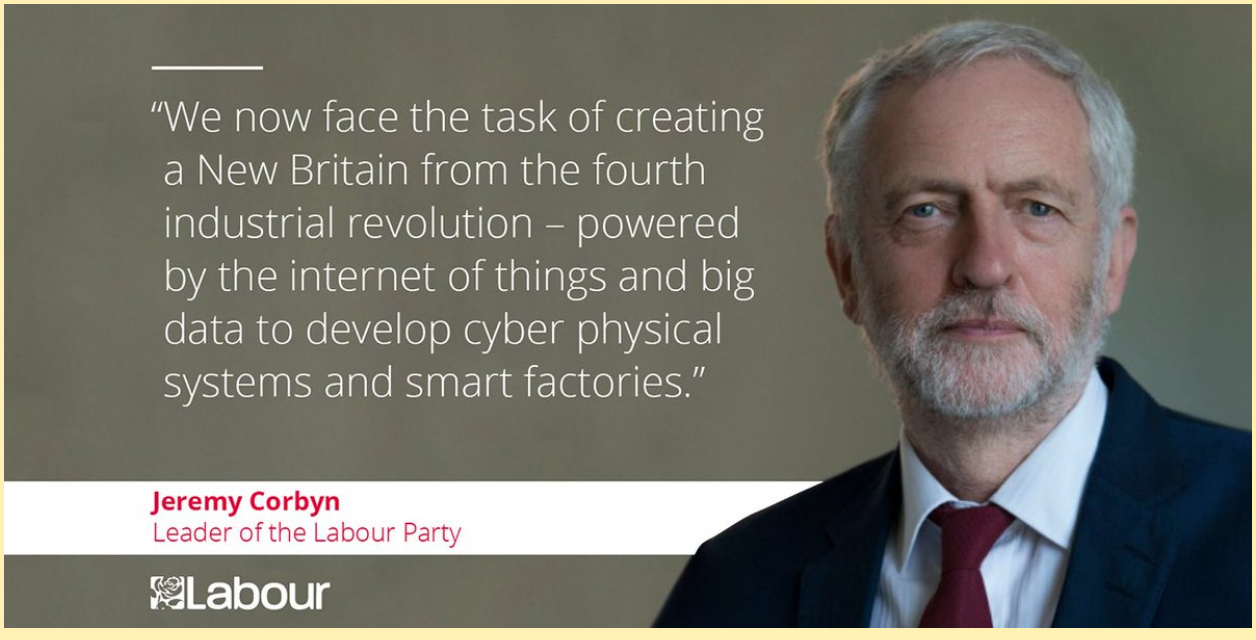

And it’s here that we need to seize the argument. There is a tweet which articulates this well. It says “you’d have to have your head in the sand to see the automatic checkouts in the supermarket and think immigrants are taking your jobs”. Yet automation is deemed to be an issue limited to policy wonks and the tech obsessed. When Jeremy Corbyn said “we now face the task of creating a New Britain from the fourth industrial revolution –note powered by the internet of things and big data to develop cyber physical systems and smart factories”, the internet was alive with people mocking him. Yet we know that many of the jobs of today will be automated out of existence in the next decades by machine reading, driverless vehicles and vastly expanded data processing power.

Image macro produced by Labour.

And progressives have no story to tell about this that might make people vote for us as that future arrives. We have abandoned that territory to Trump, le Pen and Farage with their elitist and dystopian dream of a white-power version of the 1950s. We urgently need a political economy of automation, the data rich world and the end of the long industrial revolution.

There are the beginnings of such an approach with the excellent work being done on citizen’s income. But that alone isn’t anywhere near enough. Because the changes coming to our society have wonderfully liberatory potential; a potential we can harness if we seize the opportunity to subjugate these new trends and technologies to a story about the world we want.

But to do this, it’s important to distinguish between two things: jobs and work. On the one hand, the destruction of jobs as we know them isn’t something most people will mourn. On the other, the value of work and the purpose it gives our lives is something we already mourn in the loss of manufacturing jobs. The mistake is to conflate these two things.

We can use automation to replace the drudgery of jobs carried out for other people’s purposes – work that is alienated. And we can focus our lives on the tasks that both make us human and that humans do best. Those things are caring and creating. Oscar Wilde famously observed that “the trouble with socialism is that it takes too many evenings” – less requirement to do alienated work means more time to discuss and agree our future.

People love caring for their families, their friends and those in their community, and the human connection required for true care cannot be replaced by machines. And people love being creative, making things, having dreams and communicating them in pictures and music, and writing and performance and all manner of arts. In ancient Greece, the morally abhorrent practice of slavery freed the slave owning class to be creative, and they were able to lay the foundations of Western science and literature. Automation means that we can unleash the talent and potential of all our people without resorting to the horror of slavery.

So what is to be done?

We have a choice over the future. It doesn’t have to be a choice between a return to a fantasy 1950s or the perhaps-benevolent technocracy of Silicon Valley. Much of the world we are entering depends on information rather than material property. In this sense, it is like the commons that we have always struggled to govern.

And so to understand it, we need to answer a question which our society profoundly struggles to answer. In fact, the greatest crisis of our age – climate change – occurs because our way of governing finds it difficult to incorporate those things that can’t be enclosed and owned into its frameworks or take more than a single term in office to solve. It is clear how a person, a company or a country can own land or buildings or even ideas. It is very difficult to see how the atmosphere can be owned. So, for most of the modern era we didn’t even try. And the result was massive damage to a common that underpinned all life on earth – the environment.

But there is hope. The only woman to win the Nobel prize in economics, Elinor Ostrom, did her life’s work on the commons, showing that societies throughout history have found successful ways to manage them, collectively.

Following her lead, we must develop an economics of the commons to replace the discredited neo-liberalism that has failed so badly since the crash. This economics of the commons must incorporate a system to manage the massive amounts of information now being accumulated about us and our lives. It must offer a way beyond the economics of false resource constraints and it must create an attractive vision of the future.

The most important commons we need to develop a way of governing is the environment. Much of our current economy is based on displacing the costs of doing business into the environment. Either as pollution, or through climate change, price mechanisms can’t and don’t measure the impact of environmentally damaging externalities – you only need to see the failure of carbon pricing initiatives to understand this. And the persistence of free market ideology only makes this more difficult.

This new way living our lives will mean spending much more time negotiating who gets to use what and when. It will mean much more democracy, especially at local levels, as we negotiate the opportunities and limits of the fully automated, data rich world we are entering.

To do this progressives must distance themselves from technocratic governance – while sexism no doubt played an important role in Hillary Clinton’s defeat, a critical factor was the perception that she was perceived as an elite politician representing only an elite who were responsible for the crash of 2008 (this also explains the failure of many of the other Republican nominees, most notably Jeb Bush).

We have allowed the hard right to play at being anti-elitist for too long – the Koch brothers have spent huge sums on creating astroturf (fake grassroots) organisations. We need to become much more vocal in our criticism of the establishment. The approach taken by Podemos in Spain and by Bernie Sanders offers an insight into how this could work. We need to articulate clear demands for redistribution of wealth, for community control of resources such as energy and facilities and for radical democratisation of every aspect of our shared lives.

This is by no means a fully developed programme. It is a call to action and discussion. We need a plan, a story and a vision. Because without one we can’t win. But with one we can unlock the potential of a new world where we can all be profoundly more human.