What role for the Commonwealth?

Is the Commonwealth a part-solution to Britain’s trade woes post-Brexit?

The government’s Article 50 bill cleared the Lords last week on March

13th: Commonwealth Day. Economists’ and MPs’ positions on what the

Commonwealth offers post-Brexit Britain in terms of opportunities for

trade and future prosperity have, meanwhile, become almost as heated

as those on the referendum.

In the red, white and blue corner, Brexiteers have been quick to claim

the eagerness of Australia and New Zealand to sign free trade deals

with the UK, with Boris Johnson heralding the Commonwealth’s

“stunning” global GDP share and GDP growth compared to the EU’s as an

indication of the UK’s bright prospects. Remainers are withering about

what they see as muddle-headed imperial nostalgia. “Get real,”

Conservative-turned-Lib Dem MEP Edward McMillan-Scott tweeted at his

former party colleagues Douglas Carswell and Daniel Hannan as they

welcomed former Australian premier Tony Abbott to an event earlier in

the month – Australia represents 1% of UK external trade and the UK

sells more to Belgium than to India, he told them.

“The Commonwealth is many things, many good things”, says veteran

Commonwealth diplomat, now Antiguan ambassador to the US Sir Ronald

Sanders – but it has not been a trade organization since the end of

Commonwealth Preference in 1973. At a much-vaunted meeting of

Commonwealth Trade Ministers in London on March 9th, Lord Marland,

chair of the Commonwealth Enterprise and Investment Council (CWEIC)

readily admitted that it can be no replacement for the EU for

commerce.

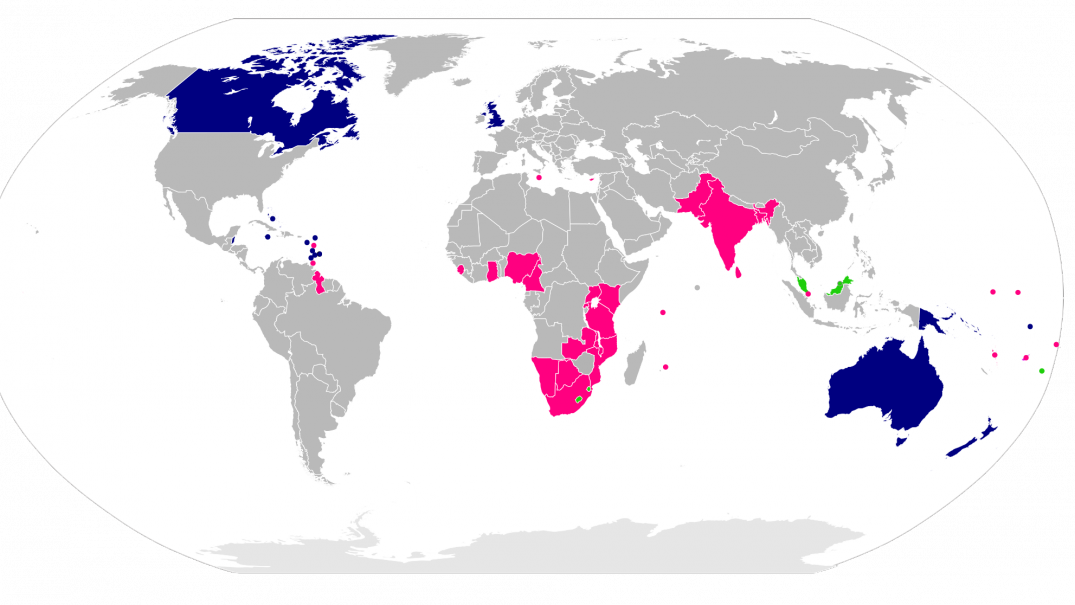

While covering a third of the world’s population, it accounts for one

fifth of the value of goods and services the UK exports to the EU, and

imports in a similar proportion (8.8% of total UK exports/10.6% of

imports compared to 44.6% and 53.2% for the EU). It represents an

assortment of wildly differing countries, from Singapore to Sierra

Leone and from Belize to Bangladesh. More than half of the

Commonwealth’s citizens are contained India’s borders. Aside from the

UK, two-thirds of its GDP is generated by India, Canada and Australia.

No Commonwealth leader outside these islands was a cheerleader for

Brexit – Narendra Modi sees the UK as India’s gateway to selling to

the EU; for Canada, Britain is its “key vector of interest” in the

European Union. Twenty Commonwealth members have free trade or

Economic Partnership Arrangements with the EU and 24 have them

pending; only 5 are entirely outside the framework.

A bilateral deal with the UK may not offer Commonwealth countries

anything more than a deal with all 28 countries of the EU, and Brexit

negotiations could delay any such agreements. The imposition of a

multilateral Commonwealth free trade area would be unwieldy and

disruptive for an equal partnership of nations. The EU has hardly held

the UK back from growing its Commonwealth trade – UK exports to the

Commonwealth rose 120% between 2001 and 2011.

There are further problems: as former HM Treasury advisor Desmond

Cohen points out, UK exports are highly integrated with European

supply chains and there is no real way of substituting these without

hugely increased costs. With a switch of trade to the Commonwealth, UK

exports to the EU may fall foul of rules of origin requirements and

get hit by higher tariffs. Economist Pankaj Ghemawat’s work on how a

common language and shared imperial history boosts trade is cited by

Commonwealth optimists – yet Ghemawat says those factors are

outweighed by others in favour of the EU because of the distance of

Commonwealth countries from each other and their GDP levels. And while

Tony Abbott calls for a one page UK-Australia Free Trade Agreement,

Tony Blair’s former Europe Minister Denis MacShane points out that the

Australian Labor party sees a bilateral deal with the UK as a

“third-best outcome”.

These are powerful and perfectly logical arguments. But the reports

making them tend towards catastrophist thinking – eg countries that

have free trade agreements with the EU being unwilling to sign mirror

agreements with the UK – and fail to reconcile themselves with the

political circumstances of the vote for Brexit, and a government

intent on carrying it through, with Parliament’s support. They also

take altogether too much pleasure in the spluttering colonel

stereotype, suggesting all Commonwealth trade advocates hanker after

lost Empire, rather than look at the more humdrum things many are

actually saying: about member states’ youthful populations, fast

growth rates and common legal systems, and how the Commonwealth is a

useful jumping off point for the UK to achieve a full complement of

global trading partners.

On the eve of the Trade Ministers’ meeting, for example, the Royal

Commonwealth Society (RCS) was keen to promote its polling showing UK

businesses’ enthusiasm for the government to prioritise trade with

Australia, Canada, Singapore and India – an impetus for trade ties

from the grassroots up. The 17% year-on-year fall in sterling

following the referendum result has indeed given a fillip to British

exports (equivalent to a 7% boost by the start of 2018, according to

Standard & Poor). For Tim Hewish of the RCS, it is vital not to talk the UK down,

there are “small and symbolic things Britain can do to gear the wheels

of trade agreements with countries keen to trade with us” – however

confounding those agreements may in reality be to sign – and civil

servants carping about “Empire 2.0” is a travesty.

Hewish and others see international trade in starkly moral terms, with

the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences offering, for instance,

tariff-free trade on agricultural produce while tariffs remain on

processed goods locking some developing countries into pernicious

dependency. The Legatum Institute’s Shanker Singham, a former trade

official, describes “extraordinary, Alice through the Looking Glass

conversations” with ministers urging preferences to be maintained,

with the added result that poor UK families pay more for their food.

(The EU Commission denies its trade policies have held back

development, a claim that backbench Brexiteer Peter Bone MP dismisses

as “lying”, pointing to the size of the German coffee processing

industry). With some lower income countries diversified enough that

they would welcome free trade, the time is ripe for change – Hewish

thinks that “you can eat values for breakfast”, with populations

becoming wealthier under free trade that in turn gives them more say

in how their taxes are spent, empowers women etc.

In a speech at the Guildhall last Tuesday, Lord Howell argued that

with the fragmentation of production processes and the emergence and

rapidly falling cost of new communications technology, world trade is

undergoing fundamental disruption. Pointing to a 2016 McKinsey report

that found digital information flow now has more impact on GDP growth

than trade in goods, he says that the service-dominated UK is ideally

placed to benefit and that the Commonwealth’s dispersed network fits

the future trade blueprint “like a glove”. Sir Ronald Sanders retorts

that it is a fallacy to simply look at total value of trade – people

can’t eat services or build infrastructure out of them, the need for

commodities including oil and gas continues, and current demand for

services in the Commonwealth is very largely concentrated in a handful

of countries.

Shanker Singham thinks the brightest hope for UK trade is through

reaching “plurilateral” agreements with a group of like-minded

countries, citing the 2006 P4 agreement between New Zealand,

Singapore, Brunei and Chile which provided the backbone for the Trans

Pacific Partnership. Formulated on an open accession basis, such

agreements carry much more market clout than bilaterals because they

can quickly bring in large swathes of the world economy. Over time,

Commonwealth countries’ shared values would attract more of them to

sign up; developing countries with more liberalised economies like

Ghana and Botswana would act as leading lights in their regions.

However, the Trump administration’s withdrawal from TPP, the public

dismay over the powers ceded to corporations in global trade deals and

the UK’s circumspection over globalisation suggest that following this

approach would be as fraught as anything in Britain’s current trade

predicament.

Intra-Commonwealth trade may still be “miniscule”, but it’s a great

opportunity to diversify exports in terms of basket and destinations

to reduce the UK’s vulnerability to shocks like the financial crisis,

says Rashmi Banga, head of trade competitiveness at the Commonwealth

Secretariat. “In India, Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya and the Caricom

countries, there are openings for many new services and products – eg

infrastructure, accountancy and legal services, [or] providing the

technology to the India Smart Cities project. This is where UK

services can grow exponentially”. The inaugural India-Commonwealth SME

Association trade summit in May will present opportunities. Grow the

value of trade now, and there may be more incentive to reach free

trade deals after 2019.

Meanwhile, Trinidadian economist Marla Dukharan gives hope to the

prospect of UK bilateral deals gaining traction. In her view, regional

association Caricom has been too weak and slow-moving to represent the

Caribbean at the negotiating table, and each island should seek a more

meaningful discussion over trade bilaterally with both the UK and the

EU.

The boisterously Brexit-friendly CANZUK movement with Tony Abbott and

historian Andrew Roberts among its leading lights calls for free

movement as well as free trade across Canada, Australia, New Zealand

and Britain. What do citizens of other Commonwealth nations think

would sweeten relations between their countries and the UK? Gaston

Chee, a Malaysian with an education business operating in China and

Britain, contrasts how London and Beijing court his compatriots: it

takes three months to get a bank account in the UK but less than 15

minutes in China. As for the May government’s insistence that foreign

students return home promptly after finishing their courses rather

than encouraging them to stay to build a business, “Do you think it is

fair to have paid hundreds of thousands of pounds and not be able to

attend graduation?”, he asks.

Rajesh Thind, a British-Indian writer and filmmaker who has spent five

of the past 10 years in Delhi and Mumbai, says Indians are predisposed

towards trying to understand and to work with the UK, “but it comes

from a muscular position of wanting a good deal and the securing of

free movement”. This needn’t mean long-term immigration – “it could be

two or five to ten years. A lot of people want to train up and go

back”. Peter Bone MP says he is potentially open to this – “One of the

great things about coming out of the EU is that if we want to decide

that, we can”. Thind echoes the recent calls on Channel 4 News by

dapper Indian MP Shashi Tharoor for Britain to come to terms with its

actions as a coloniser – for much more practical reasons, to Thind’s

mind, than post-imperial guilt. “The middle-ground in India is very

self-aware that rapid growth since 1991 has been a) very unequally

distributed and b) taken place in the context of bureaucratic inertia.

Cities are teeming, infrastructure is creaking, manufacturing needs

upgrading. We need expertise and partners… We can make the Indian

success story part of the British story, but that will take a

historical reckoning”.

Brexit and its consequences occasion radical and courageous fresh

thinking. The Commonwealth might yet assume an unexpected role in the

UK’s economic future – but this might take a brave new departure by

the immigration-chary May government, too.