Celebrating the 800th anniversary of the Charter of the Forest

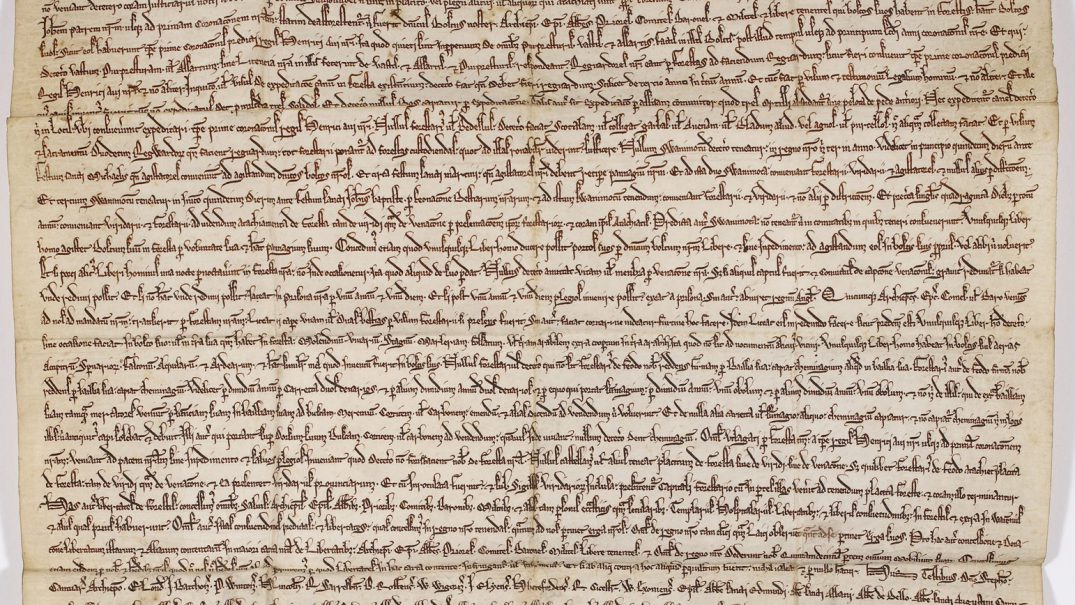

The Forest Charter. The British Library. Public domain.

This year is the 800th anniversary of a founding document of the British constitution, and of other constitutions as well. Issued in the name of a ten-year-old King Henry III alongside the modified Charter of Liberties that had been sealed by King John and the barons at Runnymede on June 15, 2015 that became Magna Carta on November 6, 1217, the Charter of the Forest is among the first ecological charters in history and among the first to assert the rights of the common man and woman.

As it coincided with the first feminist advance, in a modified Article 7 of the Magna Carta, which could have been in the Forest Charter, it could also be called a first feminist charter. That new Article 7 gave widows the right to refuse to be remarried, to retain some of their husband’s land and to have the right to estovar on the commons, to take the means of subsistence, for the remainder of their lives. In effect, widows were given the right to a basic income. For the time and place, that was a remarkable advance.

The Charter has the distinction of being the most durable piece of legislation in British history, having only been superseded in 1971, with the Wild Creatures and Forest Laws Act, by when most of its principles had been embedded in other legislation, including the Commons Act of 1876, which ruled that enclosure should be allowed only if there were public benefit, and by the establishment of the Forestry Commission in 1919.

The legislation that chipped away at its principles turned it from being a fundamental assertion of common rights to a generalised plan to handle nature and turn it into resources, for production and commercial ends. From its origins as a great act of decommodification of commoners it gradually evolved into a body of legislation and institutions for the managed commodification of natural resources.

Yet the Charter is almost unknown, rarely mentioned in children’s history lessons. Almost certainly, this is because it is an assertion of the rights of ordinary people to the right to subsistence. Yet for hundreds of years after 1217 it was more influential than the Magna Carta itself; every church was required to read it out four times a year in designated services.

Some historians believe that it was the Charter of the Forest that carried the Magna Carta forward in the centuries after they both came into effect, not the other way round. This was partly because the commoners were obliged to struggle to maintain the rights to subsistence enshrined in the Charter.

Rights always begin with class-based demands made against the state. The Forest Charter was about restoring and preserving the right to common, the rights of commoners and their right to the commons. Of course, it was incomplete in all respects, and is hard to read, with words and concepts that have drifted into history, such as agistment (right to use the commons for livestock) and pawnage (right to pasture your pigs). Even the great verb ‘to common’ is scarcely recognised today, though users of it have a twinkle in their eyes in perceiving a revival.

The context of the Charter in 1217 was the aftermath of a period in which the monarchy, notably King John, had begun to use the forests to extract rents and fines, had curtailed the rights of commoners to use the land for their subsistence, and had imposed heavy sanctions on behaviour that did not serve the interests of the elite. Forests symbolised the land, since half the country was covered by them, but the idea of the forest covered much more than it conveys today. It included all forms of public, common spaces, including villages and towns.

What the Charter did was nothing less than provide a legal foundation for living, by asserting the commoners’ usufruct rights, the right to subsistence, on common land and water. It also asserted the right to reparation, if the high and mighty encroached on the commons, through commercialisation of its products, enclosure or encroachment.

The Charter of the Forest has been integral to class struggle throughout British history. Tweet This!

It has influenced class struggles in many parts of the world. For many years after 1217, it carried the Magna Carta forward, rather than the other way round. It provided the basis for riots in defence of common rights. But it has been abused throughout its history, with the Tudors being egregious spoilers. For centuries, commoners protested against the threat to the commons, most notably in the 17th century in a series of riots that helped to precipitate the Civil War.

Although formally superseded in 1971, the ethos of the Charter has been preserved in several institutions. The closest it came to defeat was the Coalition Government’s plan in 2010 to privatise the Forestry Commission. The plan was withdrawn after concerted public protests. But those who wanted to implement it are still in government or in the circles of influence supporting it.

Now, its values are under more surreptitious attack, through the micro-politics of privatisation. The government is deliberately running down the management of the commons, to the point where more and more people will not care whether it is privatised, commercialised or simply lost. We are at a critical point.

We must use this anniversary year to revive and to defend the Charter’s principles, including its assertion that every commoner has the right to subsistence. It is a wonderful opportunity to organise a series of events to celebrate, defend and revive the commons, thereby exposing the ideology behind the ongoing plunder of the commons and the micro-politics behind it.

In short, a tragedy of the neo-liberal era (roughly since 1980) is that, as rentier capitalism has grown by the extension of private property rights, the state has orchestrated a plunder of the commons, against the spirit of the Charter of the Forest.

We may divide the commons into five types – spatial (or natural), social, civil, cultural and intellectual or educational.[i] The spatial commons are the foundation – land (and what is on or under it), water and air. They are natural assets that belong to all of us, as citizens. They do not belong to any government, just as they do not belong to any individual owner. They convey an array of common rights, including the right to roam. They are ‘nature’s bounty’ handed down to us by our ancestry. They were either never privatised or at some time became part of the commons. They belong to us collectively, and belong to nobody. Parts of the commons were improved by the labour of numerous people put to work in a public cause.

The social commons consist of amenities created and paid for by generations before us, including public libraries, public hospitals and clinics, public transport systems, public roads and squares, and parks and public gardens that are a combination of spatial commons and the efforts of numerous people who have shaped their design and their character.

The cultural commons include public art, for which we as society are stewards, not owners with a property right to buy and sell. One ugly aspect of the austerity era has been the stealthy selling of art works from public museums and public places, the most symbolic of which has been the tussle over Henry Moore’s statue, Old Flo, which he bequeathed to the borough of Tower Hamlets to give beauty to a public space.

Other works of art have been sold under duress, in a buyers’ market, in response to budget cuts forced by central government, so that the latter can continue with its policy of cutting taxation for affluent groups and its donors. If we knew the full extent of what has been done and what is planned, perhaps we would riot. We should.

The fourth form should be called the civil commons, encapsulated for eternity in the Magna Carta of 1217. These may be defined as a universal and equal right to justice, with respect to due process, affordable and accessible legal representation and so on. It is insufficiently appreciated how far those principles have been eroded in the past three decades. The current Government is merely continuing what New Labour and the Coalition accelerated, which is perhaps why there has been little parliamentary opposition to its erosion. If the right to legal aid is lost, the civic commons is eroded.

Privatising social and employment services has also been a means of shredding the civic commons. There is no due process in welfare sanctions and benefit denial. We should demand it, in the name of the rights of commoners.

The final form is the educational or intellectual commons. Think of our great universities and colleges. They should not be commodities to be bought and sold, or turned from bodies for nurturing learning, scholarship and research, and a culture of reflection, into an industry for maximising profits by churning out breadwinners, degrees and commodified academics. The educational commons must be rescued by reversing the commodification of education

The several types of commons – spatial, civil, social, cultural and educational – are integral to a good society. They have a value in themselves and contribute disproportionately to the social income of low-income groups in society.

The primary tragedy of the commons is not what is usually regarded as the depletion by over-use by commoners. It is that successive utilitarian governments, wedded to neo-liberal economics and private property rights, have seen all forms of the commons as resources and as capital, to be turned into revenue. The austerity rhetoric has been used to accelerate the plunder of the commons. Under the guise of decentralisation, the Government has made local authorities more responsible for the commons, and then cut their budgets, leaving under-funded authorities with painful choices. Most have buckled.

This is a wilful ideologically-driven campaign to privatise, enclose and commercialise the commons. Consider just a few examples. The iconic Sheffield public library is to be sold to foreign capital, so that it can be turned into a five-star hotel. That library belongs to the people of Sheffield, and not just today’s people, who are the stewards of the commons for the generations to come. In the same city, the authorities have turned the care of public trees along roads to a private firm, which has promptly cut down thousands of trees, on commercial grounds.

What is happening to our parks is scandalous. For instance, with its budget slashed, the authorities in the Lake District, an iconic part of our commons, have put prime sites up for sale to private buyers. In the Royal Parks, bequeathed to the nation by Queen Victoria for the use by rich and poor for rest and recreation, commercialisation is being allowed, rationalised by a need to raise money for their upkeep because of government budget cuts. A result is ‘eventism’, commercial events that shatter the calm and leave the grass needing months to recover, thus denied to the commoners.

Allotments, that wonderful legacy of commons for growing fruit and vegetables, and for connecting people to nature, are under commercial siege, some being converted to car parks or sites for supermarkets. The privatisers and their rich clients have no moral right to take it away. And yet they are being allowed to do so.

Then there is fracking, denuding our spatial commons. The Energy Secretary said before the General Election in 2015 that there was ‘an outright ban’ on fracking in national parks. Immediately afterwards, the same Minister said drilling would be allowed around and under them. Shamelessly, the Government has also hastily politicised the granting of drilling licences, bypassing democratic processes. It has no right to do this. Whether or not we favour fracking (and most of us do not), this year we should make it a matter of fighting to preserve the commons.

Then there is the farce of the Garden Bridge over the Thames in London, mercifully killed by the Mayor of London. The national river is part of the commons. A bunch of privateers, orchestrated by a well-connected actress, should not be allowed to build a private bridge, much of the time to be closed to the public, and to receive millions of pounds of public money and loan guarantees to enable them to do so. That is what happened. Happily, the new Mayor has killed the project. But one would be naïve to think it will be the last of its kind.

Meanwhile, the erosion of the social commons is extraordinary, with social housing, libraries, public toilets and much else quietly being lost. Thousands of routes of public bus services have been closed, which were used predominantly by low-income people. When libraries, bus services, allotments and parks are shrunk, the social income of the precariat falls, because low-income people, particularly those in and out of short-term jobs rely on public spaces and amenities much more than the affluent, who have their private cars, gardens and second homes.

Taking away the intellectual commons has been a globalisation trick. In 1813, Thomas Jefferson said that ideas cannot be property, and yet in the current era institutional and regulatory mechanisms for privatising so-called intellectual property have been built into a fortress since the passage of TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Property Rights) in 1995. Patents, copyrights, trademarks and other wheezes have proliferated, all giving monopoly income flows for many years, sucking up rental income for those perceived to own ideas.

Supposedly a return to risk-taking, many patented ideas are actually the result of generations of ideas produced by numerous people. Many result from publicly funded research, in public universities, colleges and research institutes. Many are filed with the intention of just being artificial barriers to entry, not for actual use. They are the base of rentier capitalism. In this year of the Charter that established the rights to the commons, there should be a campaign to roll back so-called intellectual property rights. They enrich plutocratic corporations that are patent hoovers, buying up thousands of patents and stringing them together to earn billions of dollars, pounds or euros.

What should have priority in this momentous year? Let us demand that every local authority identify and produce an inventory of all commons under its stewardship or the stewardship of central government. Let us demand that no piece of the commons should be enclosed, commercialised or sold without public knowledge, proper public debate and adequate time for contestation. Instead of having referenda for complex issues that people cannot be expected to understand, let us have them around simple acts of plunder of the commons.

Let us expose the false vocabulary that conceals the plunder. To call a government body the National Capital Committee is a provocative, ideological trap. The commons are not capital. The fact that the Committee was set up by a ‘business-led Ecosystem Markets Task Force’ designed to ‘harness City financial expertise to maximise revenue streams’ tells us of the commercial priorities, a shield for a plunder that must be resisted. The voice of the commoners was excluded.

Let us demand an inventory of the POPS (privately owned public spaces) that are being spread surreptiously in cities and towns, demand to know why they are being allowed and demand that they be stopped. No POPS without representation by commoners! Why should a Malaysian business consortium be allowed to turn an iconic part of London into a mock Malaysian jungle? It should be part of London, embedded in the traditions and culture of generations of its commoners.

Let us demand our urban spaces back. Think of the implications of an injunction issued barring protesters from the Broadgate Estate covering Bishopsgate and Liverpool Street. It said pompously and arrogantly, ‘The are no public rights over the common parts.’ More of our cities and towns are being denied to the commoners.

In sum, now that an ill-judged General Election has ended messily, in the second half of this year of its 800th anniversary, let us launch events across the country to celebrate and revive the values of one of the great charters of British history.

Among them, a group of us are hiring a barge to go up the Thames to Runnymede on September 16, holding workshops on critical issues en route and then a public event under the majestic Ankerwycke yew, over 2,500 years old, surely the finest tribute to the forest and the commons one could imagine in the country. There we hope to expand on a demand that the government, of whatever complexion, should organise a Domesday Book of the Commons, to be drawn up by 2020, listing all the commons that still exist. It would act as a defence line and a point from which to advance.

[i] This typology is developed elsewhere. G.Standing, The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers thrive and Work does not pay. London: Biteback.