To solve the housing crisis, we need to fix our broken land economy

Image: Images money, CC BY 2.0

The UK, along with many other advanced economies, is facing a major housing affordability crisis. Average house prices are now on average nearly eight times that of incomes across England and Wales, and up to 39 times in parts of central London.

A whole generation finds itself priced out of the market, struggling to make ends meet in the face of eye-watering rents. Over the past 15 years’ levels of home ownership have been falling sharply, particularly among young people. Homelessness is rising fast.

How did we get here? A popular explanation is ‘we’re not building enough homes’. While this is part of the answer, it is far from the whole story. At the root of the problem lies something that has for a long time been overlooked: the role of land in the economy.

But the issue of land goes far beyond the housing shortage. It lies right at the heart of many of the key challenges facing modern economies, from mounting inequality and financial instability, to intergenerational conflict and poor prospects for sustainable development.

To understand land properly, we must take a cross-disciplinary approach – we need a bit of history, a bit of economics and a bit about power and the law.

Theft and freedom: the paradox of property

Land is essential for all activity to take place, and indeed for life itself. Nobody ‘created’ land, it just exists. And we can’t create any more land, even if we wanted to. Land is not simply soil, and its economic uses are not simply agricultural. In economic terms, land is better understood as a set of legal rights over physical space.

Land first began to be treated as tradable, private property in the 16th century, triggering the birth of modern capitalism. But this transformation gave rise to a tension. On the one hand, landed property empowered people by providing physical and economic security, including collateral to leverage credit, which helped drive economic growth and technological advancement. But at the same time, private property in land was inherently exclusionary: by its very nature, granting some people exclusive rights over what was previously a common resource involves taking away the rights of others. Millions of people were driven off the land, often violently. Those who were allowed to stay found themselves having to pay rent to landlords to access what had previously been available for free. Landowners became the gatekeepers to an essential resource, a role which meant they were able to absorb much of the value that was being created in the economy in the form of higher rents.

The introduction of private property therefore brought economic power to some and dispossession to others – a paradox that was perhaps best summed up by the anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who said that property was both “theft” and “freedom”.

Fast forward to the 21st century and this paradox is alive and well, it just manifests itself in different way: this time through the housing market.

Land in the Twenty-First Century

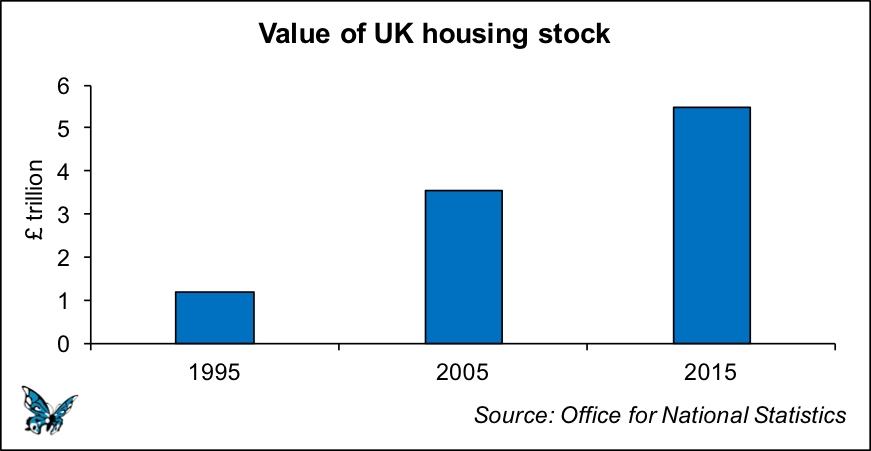

Today the value of the UK housing stock stands at £5.5 trillion – around 60% of the entire net wealth of the UK. This has increased from just over £1 trillion only twenty years ago.

As the Office for National Statistics acknowledges, this rapid increase is largely the result of soaring house prices:

“The increase in the value of dwellings was largely due to increases in house prices rather than a change in the volume of dwellings.”

But the price of a property is made up of two distinct components: the price of the building itself, and the price of the land that the structure is built upon. We don’t know the exact breakdown between these two components (bizarrely, there is currently no reliable public dataset on the land market in the UK) but the available data implies that land under homes is currently worth around £3.7 trillion – nearly 70% of the total value of the housing stock. This makes residential land the UK’s most valuable asset, even in today’s high-tech economy.

So why is land so valuable? And why have land values, and thus house prices, increased so much relative to incomes in recent decades?

Land values increase naturally over time as economic growth and a rising population increases demand for a resource that is inherently fixed in supply. Public and private investment in infrastructure and amenities also increases the value of land, making some locations much more valuable than others. For example, new transport links or being in the catchment area of a good school can dramatically increase the market value of nearby land. As a young Winston Churchill said in a famous speech to Parliament in 1909:

“Roads are made, streets are made, services are improved, electric light turns night into day, water is brought from reservoirs a hundred miles off in the mountains – and all the while the landlord sits still. Every one of those improvements is effected by the labour and cost of other people and the taxpayers. To not one of those improvements does the land monopolist, as a land monopolist, contribute, and yet by every one of them the value of his land is enhanced.”

There is also good evidence that as economies mature, the demand for land relative to other consumer goods increases. Land is a ‘positional good’, the desire for which is related to one’s social status. In economics jargon, land has a ‘high income-elasticity of demand’ – people will stretch their incomes to consume it. This goes some way to explaining why the rise of information technology and globalisation has not meant ‘the end of distance’ as some predicted, but has driven the economic pre-eminence of a few cities that are best connected to the global economy and offer the best amenities.

But this is only part of the story. The land economy is most decisively shaped by the laws and regulations that govern the ownership, trade and use of land. In other words, the rules of the game matter. But these rules have very little to do with economics, and much more to do with politics and power. They have varied immensely over time reflecting the evolution of power and class relations in society.

From a place to call home, to a financialised asset

After the end of the Second World War, council housing provision, tight mortgage regulation and taxes on property kept supply up and house prices (land prices) under control. The Labour government’s 1947 Town and Country Planning Act 1947 kept land in private hands, but nationalised the right to develop it – meaning that landowners and developers had to apply to their local authority for planning permission to build new property. Strong compulsory purchase powers enabled land to be acquired at low cost for housing development. This system was perhaps most successfully embodied in the New Towns programme which began in 1946.

For each New Town, a public development corporation was established which purchased land compulsorily at agricultural prices, drew up a comprehensive masterplan for the town, and then built the necessary infrastructure using money borrowed from the Treasury. They granted planning permission on the sites they owned and sold them to private house builders, using the uplift in the value of the land to repay the loans. This combination of low-cost land acquisition, strong plan-making and the power to determine planning applications proved to be a powerful means of delivering affordable housing.

But beginning in the 1960s this began to change. Taxes on property were removed, beginning in 1963 when the ‘Schedule A’ income tax, a tax on imputed rental income, was abolished. When capital gains tax was introduced in 1965 an exemption was made for primary residencies. Subsidies for buyers were also introduced: in 1969, the government introduced mortgage interest relief at source (MIRAS) which provided tax relief for interest payments on mortgages. Court judgments on compensation (particularly the Myers case of 1969) reinstated the principle that landowners should be able to claim ‘hope value’ on any land compulsorily purchased. This increased the price of land and ended the ability of public authorities to capture land value uplifts to fund new development – the model which had so successfully been used to build the New Towns.

With the arrival of Margaret Thatcher, the government withdrew from large scale house building, and councils were forced to sell their housing stock through ‘Right to Buy’, and prevented from building more. There was a shift away from supply side subsidies of ‘bricks and mortar’ towards demand-side subsidies of paying housing benefit to boost households’ incomes to enable them to access accommodation. Whereas in 1975 more than 80% of housing subsidies were supply-side subsidies intended to promote the construction of social homes, by 2000 more than 85% of housing subsidies were on the demand side aimed at helping individual tenants pay the required rent. Today the UK government spends an eye watering £25 billion on housing benefit.

Perhaps the most significant changes came with the liberalisation of the mortgage lending market. Before the 1970s, mortgage lending was mostly carried out by building societies. But beginning with the Competition and Credit Control Act of 1971, restrictions on lending were removed, and banks were incentivised to become active players in the mortgage lending market. This unleashed a flood of new mortgage lending into the economy, which increased from 20% of GDP in the early 1980s to over 70% before the financial crisis. An ever increasing supply of credit interacted with a fixed supply of land, fuelling a house price boom. In turn, households were forced to take out ever larger mortgage loans to get on the housing ladder. Thus, a feedback loop emerged between mortgage lending, house prices and ever increasing levels of household debt. The changes in credit supply conditions have been described as the ‘elephant in the room’ when it comes to understanding the behaviour of house prices, land prices and consumption in advanced economies.

The normalisation of double digit house price growth, combined with the expectation that house prices will continually increase, fuelled demand for houses as financial assets. Whereas fifty years ago houses were mostly regarded as simply somewhere to live, today homeownership is viewed as a means of accumulating wealth and long-term security in the face of stagnating wages and dwindling pensions. Although attempts to widen access to the benefits of homeownership succeeded for a while, eventually a tipping point was reached: prices are now so high that a whole generation finds completely itself priced out of the market, and levels of homeownership have been falling for 15 years.

The Great Divide

In recent years there has been a growing public debate about the causes and consequences of the widening gap between rich and poor, and the impact it has on our societies. In his bestseller ‘Capital in the Twenty-First Century’, Thomas Piketty argues that the rising inequality observed in recent decades is explained by a tendency for the rate of return to wealth to exceed the economic growth rate, causing a growing accumulation of wealth among those who already have it (a relationship he describes as r > g in notational form). When the return on wealth significantly exceeds the growth rate of the economy, Piketty states that inherited wealth grows faster than output and income.

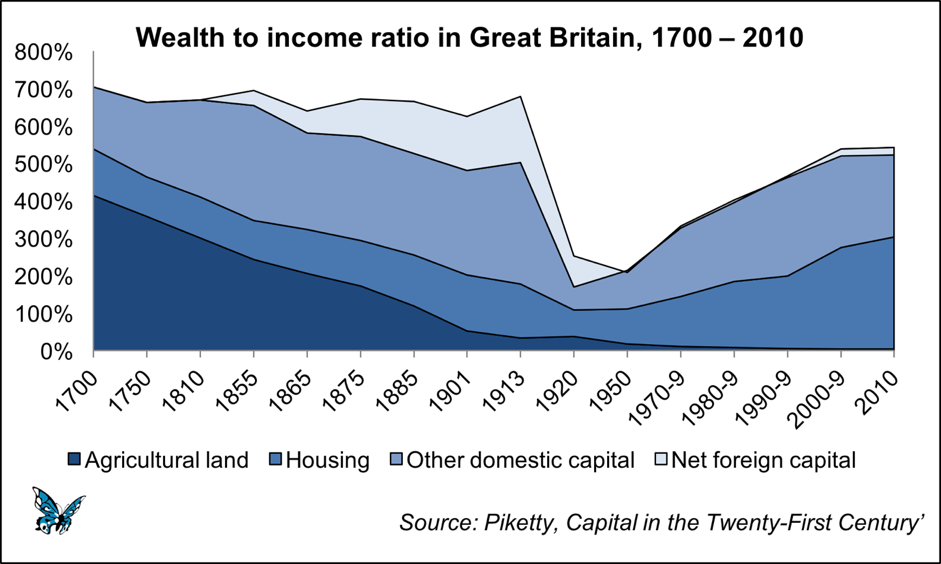

Seen in the context of the UK, this explanation would appear to carry some weight. In recent decades growing economic inequality has been accompanied by a rapid increase in the amount of wealth relative to national income (the so-called ‘wealth-to-income’ ratio). Following a significant decline in the first part of the twentieth century, the ratio began to rise the 1950s and saw a marked increase after 1970. The return on wealth has significantly exceeded the growth rate of the economy for many decades now.

However, on closer inspection Piketty’s dataset indicates that much of the increase in the wealth-to-income ratio observed since 1970 is the result of capital gains from housing – or more accurately, from rising land values. Once the effects of housing are removed, the underlying wealth-to-income ratio has actually fallen significantly in the UK since 1970.

However, on closer inspection Piketty’s dataset indicates that much of the increase in the wealth-to-income ratio observed since 1970 is the result of capital gains from housing – or more accurately, from rising land values. Once the effects of housing are removed, the underlying wealth-to-income ratio has actually fallen significantly in the UK since 1970.

The implications of this are vital for understanding the dynamics of growing inequality in recent decades. It means that the increase in the wealth-to-income ratio observed in Piketty’s data, which has underpinned the rise in inequality, has been driven not by skills or technological advancement, but rather by increasing residential land values which have manifested themselves through rising house prices.

Some economists defend rising inequality on the basis that some people getting richer is not a bad thing, so long as nobody else is being made poorer. But in Britain this is not what has been happening, because housing wealth is fundamentally different to other forms of wealth.

When the value of land under a house goes up, the total productive capacity of the economy is unchanged or diminished because nothing new has been produced: it merely constitutes an increase in the price of the asset. For those who own property, rising land prices generate an unearned windfall gain which increases net wealth. This provides immense benefits to homeowners – housing equity can be converted into income via home equity withdrawal, increasing spending power for a new car or holiday, or it can be used to leverage up further, perhaps buying a second-home, or entering the Buy to Let market.

But rising land prices also has a corresponding cost: those who don’t own property see their rents increase, or have to save more for a deposit. This cost is not captured in wealth data such as that compiled by Piketty, because under current national accounting frameworks only the capital gain feeds through to measures of wealth; the present discounted value of the decreased flow of resources to those who don’t own property is not captured.

The reality is that the housing ladder is rather like a zero sum game. Much of the wealth that has been accumulated in recent decades has come at the expense of current and future generations who do not own property, who will see more of their incomes eaten up by higher rents and mortgage payments. The key dividing line running through society today is not wealth accumulation from entrepreneurialism or hard work, but ownership of property and the ability to capture unearned windfalls from rising land values. The paradox of property is back with a vengeance, and it is driving society apart.

As spiralling house prices render homeownership increasingly unaffordable for much of the population, this divide is set to grow larger. In some lucky cases, people will be rescued by Mum and Dad as housing wealth is passed onto some of the next generation via inheritance. Already the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ has become the ninth biggest mortgage lender in the UK. But many others will miss out.

Not only is this not particularly fair, it’s also not particularly efficient. Rising land values suck purchasing power and demand out of the economy, reducing spending and investment. The availability of comparatively higher returns from relatively tax free real estate investment crowds out productive investment, both by the banking system itself and non-bank investors. This may help us explain – at least in part – the great ‘productivity puzzle’.

The forgotten factor

The early pioneers of political economy – Adam Smith, David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill –acknowledged that land had unique qualities, distinct from capital and labour. They recognised that land was a free gift of nature, and considered returns earned from the ownership of land to be unearned – referring to these windfalls as ‘economic rent’. They believed that the ability to extract economic rent was so powerful that landowners could effectively absorb much of the value created in an economy. It was feared that this could undermine the political legitimacy of the private property system itself, and so they sought to limit the extent to which landowners could make unearned windfall gains at the expense of the rest of society.

Since then, the concept of economic rent has been expanded to cover any excess returns derived purely from the possession of a scarce or exclusive resource, unrelated to the costs of bringing it into production. Today a good deal of economic regulation exists to limit economic rents that arise from monopoly power, for example in the water, energy and rail sectors, because it is recognised that these rents are both inefficient and unjust. Strangely, however, the original and largest source of economic rent – that arising from land – gets a free ride.

Over the past hundred years land has been increasingly marginalised from economic discourse in the developed-world. Today’s economics textbooks mostly neglect land as a distinct factor of production, instead conflating it with capital in the still dominant ‘two factors of production’ models. Meanwhile, theories of distribution still follow the tenets of ‘marginal productivity theory’ which states that ‘income’ is understood narrowly as a reward for one’s contribution to production, whilst wealth is understood as ‘savings’ from deferred consumption.

Although presented as an objective theory of distribution, marginal productivity theory has a strong normative element. It paints a picture of a world where, so long as there is sufficient competition and ‘free’ markets, all will receive their just reward in relation to their true contribution to society. But marginal productivity says nothing about the rules around the ownership of factors of production – not least land – which are essentially political variables. For economists who see their discipline as a ‘value free’ science which is separate from politics, this is uncomfortable territory. The result is that unearned windfalls resulting from land ownership – the largest source of economic rent – are overlooked.

But these windfalls play an enormous role in a country like Britain, where much of the wealth accumulated in recent decades has come from housing. The classical economists would have viewed this as the accumulation of unearned economic rent; a transfer of wealth from the rest of society towards land and property owners. But in Britain, these windfalls are celebrated — house price inflation is hailed by economists and the media alike as a sign of economic strength. The cost this imposes on the rest of society is ignored. As John Stuart Mill wrote back in 1848:

“If some of us grow rich in our sleep, where do we think this wealth is coming from? It doesn’t materialize out of thin air. It doesn’t come without costing someone, another human being. It comes from the fruits of others’ labours, which they don’t receive.”

Putting land back into economics and policy

How then to deal with these challenges? Firstly, the teaching of economics and related disciplines needs to be reformed to reaffirm the role of land. Practitioners across the field should seek to highlight land’s role as a distinct factor of production separate from capital, and a set of legal rights over the use of economic space. The role of economic rent should be placed squarely into theories of distribution and taxation, and the interaction between the value of land and the macroeconomy must be taken more seriously.

When it comes to policy, there is no quick fix. Because legal frameworks are essential for land to become property at all, any analysis of the land problem that starts from the premise of minimising state involvement cannot succeed. There can never be an entirely free market in landed property. Instead, policymakers need to start getting their hands dirty.

Compulsory purchase laws should be changed to enable public authorities to purchase land at agricultural prices, enabling the planning and development uplift to be captured for public benefit once again. A new National Land Bank should be established and made responsible for developing and leasing land, acquiring idle and vacant land for resale, and developing more New Towns. Planning authorities should be given more resources and stronger powers of plan making or zoning so that planning can be a ‘market maker’ rather than a market stifler.

Housing policy should seek to level the playing field between tenures, in terms of taxation and subsidies, so that people are not incentivised to invest in property over more productive assets. The stock of non-market housing, like social housing and community-led schemes, should be expanded in order to lessen dependence on the volatile market in land and homes. Taxation should be used to capture the unearned windfalls landowners currently pocket at the expense of society at large. This could be achieved by replacing council tax with a tax on the unimproved value of land.

Bold steps should be taken to break the positive feedback cycle between the financial system, land values and the wider economy. This should involve wide ranging changes to the regulation, ownership and structure of the banking sector to direct lending away from property and towards the productive real economy.

The long term-aim must be to return to a society where houses are viewed as somewhere to live, not as vehicles for accumulating wealth. This can’t happen overnight, and it won’t be easy. The task involves taking on the unholy alliance of private developers, banks and – most difficult of all – ordinary homeowners, many of whom now view ever rising house prices as normal and just.

This may seem ambitious. But the alternative is growing polarisation in society, ever increasing levels of household debt and bleak economic prospects. If we are to create a fairer and more sustainable economy, then we must start taking land a lot more seriously.

‘Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing’ (Zed Books) by Josh Ryan-Collins, Toby Lloyd and Laurie Macfarlane is available at Zed Books and Amazon.