Fairer income tax means thinking about more than the top rate

Scottish politicians debate tax ahead of the 2016 elections. Image: BBC, fair use.

Income tax. 30 million people in the UK pay it. As taxes go, it’s reasonably well known and understood. And it’s politically salient. But discussions about re-engineering it for the 21st century seem confined to the margins.

Following the post-independence referendum Smith Commission, Scotland now has wide-ranging powers over income tax. This means that last year’s Holyrood elections were the first to really grapple with the issue. Previously, the only devolved income tax power available to Scottish parliamentarians was to increase or lower tax rates uniformly across all bands – a bit of a chocolate teapot if you’re interested in progressive taxation. Now, income tax above the personal allowance can pretty much be completely redesigned if the parliament chose to.

In the lead up to the 2016 election Scottish Greens published detailed tax proposals. The income tax plans were based on principles of progressive taxation. Progressive taxation is normally understood as “tax the rich”, but the most significant part of the Green proposals was actually its effect on low earners and in-work poverty. The proposals’ starting point was that anyone earning under the average median income should pay less tax than at present, while people earning more than the average could pay more. The purpose was explicitly twofold: to reduce income inequality and raise money to fund public services.

The effect of the proposals would have been to reduce inequality (as measured by the GINI coefficient) by four times more than proposals from the SNP, and raise an additional £331m for public services. For individuals, the data showed median income to be around £24,000 in 2013/14. Under the Scottish Green plans, everyone earning less than £26,500 per year would have seen their income tax reduced. People earning the median gross full-time annual pay in Scotland (£27,710) would have only paid £24 more.

To create the “split point” of £26,500, i.e. the point at which people go from paying less to paying more, the Basic Rate was split into two. The first section was lowered to 18% and the second section raised to 22%. This was a reasonably simple adjustment to help people affected by in-work poverty and add more progressivity to the system. To my surprise even this turned out to be depressingly beyond the creativity of other political parties. Scottish Labour in particular got tied up in knots explaining how they would protect people on low earnings from a rise in the basic rate with a “£100 rebate” administered by Councils. Eventually they dumped the policy which was generally accepted as completely unworkable. The Scottish Lib Dems seemed content to forge on with promoting a 1p rise across the board as if the most significant new power devolved to the Scottish Parliament since its creation didn’t happen. The SNP seemed content to largely just do-as-the-UK-do on income tax.

For me, this lack of creativity and narrowness of proposals for the Basic Rate (82% of tax payers pay only the basic rate) was the most surprising thing to come from the new debates on income tax in Scotland. But even this seems more lively than the eerie silence where you’d hope to hear any serious discussion of income tax at Westminster: since Brown’s abolition of the 10p rate, almost everyone has seemed content to stick with roughly the same income tax structure and to fiddle only with rates and thresholds, despite notable changes in the spread of incomes being taxed.

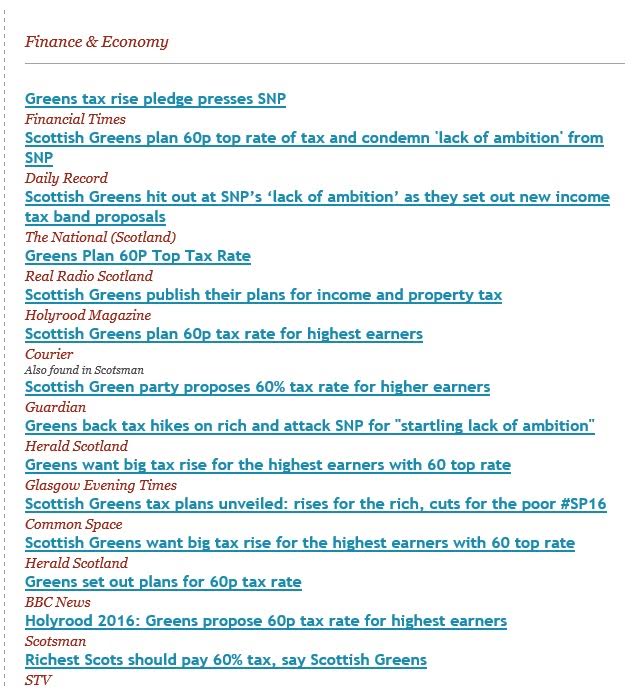

Where there has been debate, it has focussed mainly on what the top rate (paid by 1% of tax payers) should be. The day after the Scottish Green proposals were published 90% of print media coverage led with a tax change that would affect 0.6% of the population.

Headlines the day after the Scottish Green tax policy announcement were all about the top rate, despite changes elsewhere affecting many more people.

How much the highest earning in society can expect to be taxed is important – and a high Additional Rate should be used as a mechanism to promote a more equal society – but it is not the whole picture. There are other important issues that should be in the frame: for example, stemming the increase of in-work poverty, reacting to the rise of insecure work, and shifting taxation from labour to asset wealth, where inequality is significantly greater. Addressing these requires us to think across the income spectrum. And while this debate is being pioneered in Scotland, the argument for a real restructuring of the income tax system applies equally across the UK.

Note: this article wrongly listed Adam Ramsay as the author when it was first published. In fact, the author is Iain Thom.