Why the UK must invest in innovation: A view from Japan

Photo: Pexels.

According to the World Bank, since 1995 manufacturing has decreased as a proportion of the UK’s GDP from 18% to 10% in 2015. The service economy occupies a staggering 80% of the UK’s economy. In the wake of the recession Britain has faced, it seems prudent to reassess where the nation’s priorities should lie in terms of addressing the balance of the economy.

James Dyson was in the news recently, declaring his intent to invest in a specialised university offering courses to prospective students in specialised fields relating to high-tech and engineering. His stated intent was to compete with the countries of southeast Asia. These countries had a particular speciality in the innovation of manufacturing and scientific research, something Britain is at risk of falling behind in on the world stage.

Innovation of a country is only as good as the education of the workforce that produces it. In this regard countries of southeast Asia are notably world-leading. It is hardly a coincidence then that countries renowned for their manufacturing and technology sectors are also consistently the highest scorers in Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests. These tests are a means of ranking the educational prowess of world economies, with Japan most recently being the highest performing large economy in the world. This is a country that Dyson specifically listed as a chief competitor with British cutting edge research and manufacturing.

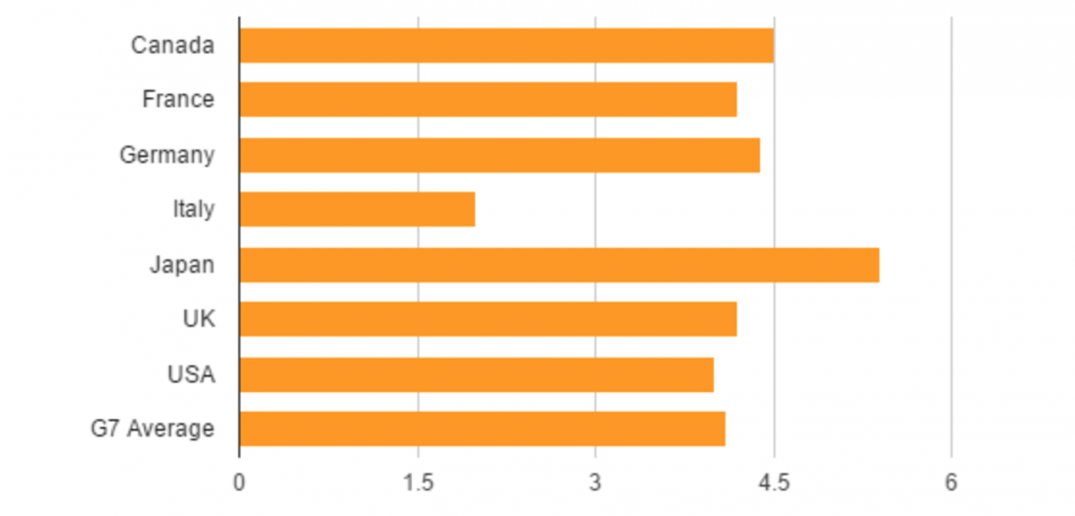

Generally worldwide manufacturing has decreased as a proportion of GDP owing to automation and cheaper outsourcing to countries like China. This means in order for countries to compete with their manufacturing and industry, they should compete on skills and innovation instead of competing on cost. Japan is an example of this trend. Although Japan’s manufacturing sector has also seen decline, though not nearly to the same extent as the UK, the number of patents applications per year has increased by 40% since 2007. Another indicator of innovation also demonstrates Japan’s researching prestige – there are 5.4 researchers per 1000 people, compared to 4.2 of the UK, and 1.28 world average.

Data Source: World Bank

Research and patents share the same common denominator of an educated workforce. According to a recent government study by the Office for Science the number of graduates will nearly double from 2002 to 2020, and although this would undoubtedly be beneficial for the economy, what may require improvement are the number of applications to STEM (Science, Technology Engineering and Mathematics) related subjects. Although they have increased with time, they are not doing so at anywhere close to the same rate, increasing by 14% from 2004-2014.

Distinguished by ‘world class universities’ and achievements in science, Japan became the technological giant it is today following the post-war years. As the STEM consultancy report authored by the Australian Council of Learned Academies notes, Japan’s solid educational foundation is the result of regularly updated policy analysis, with a particular outlook to international comparative benchmarks. A dip in the 2003 PISA rankings was due to a relaxing of the number of hours the Japanese government mandate children be taught science and maths. The shock of losing pride of place resulted in a change of the system, with the same revised curriculum but with the same hours previous to the reforms that were implemented in 1998. The result of this new adaptation is clear to see, Japan is the 2nd ranking country in PISA scores, second only to Singapore.

While Britain is Europe’s highest achieving large economy in PISA rankings on average, the scores specifically for science and maths are somewhat lacking. Britain scores only slightly higher than the OECD average. There are also regional imbalances. While Scotland, England and Northern Ireland scored above the OECD average, Wales came notably under, on par with Colombia in PISA scores.

Britain ought to take this news the same as Japan did for its ‘PISA shock’ moment, while the scores are not cause for alarm, they certainly aren’t encouraging. The score has more or less been stagnant since Britain join the international ranking.

Innovation is key for the survival of businesses operating in the high-tech sector. The previous coalition government had recognised its importance. A policy review published in 2014 highlighted the need for investment and strategy to coordinate collaboration between academia and business in several areas of technology, robotics and energy storage to name a few. The government must go further and encourage a greater intake of students to supply the knowledge and skills needed to help expand, and it must do so at an early stage of the prospective student’s’ life. Keeping an eye on the international competition, much like Japan and James Dyson, will be vital to make the manufacturing sector more relevant on the world stage, and help rebalance the economy as a whole by making Britain invaluable to an ever more technologically advanced world.